Many people are familiar with the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin’s Olympiastadion. That was the Olympics where Jesse Owens won the gold medal in track in front of Adolf Hitler and senior Nazi officials. However, did you know that Germany also hosted the 1936 Winter Olympics? (The last time both winter and summer games were held in the same country in the same year.) Somehow, Hitler obtained a “two-fer” that year for the purpose of showcasing his National Socialism party to the world.

I recently wrote a blog about a Norwegian footballer who competed in the 1936 Summer Olympics (click here to read the blog, Two Footballers and a War). Today, you will be introduced to another 1936 Olympian. This time our story is about a hockey player who played for the German national team in the Winter Olympics. What is remarkable is that Rudi was Jewish and Hitler allowed him to participate.

Did You Know?

Did you know that in 1929 the United States Navy sent Joseph Rochefort and two other young officers to Japan for three years to become fluent in the language and culture? Did the navy foresee the future conflict with Japan or was it just dumb luck? For Capt. Rochefort it was the foundation that he and his team of codebreakers needed to determine if they had enough evidence from Japanese radio messages to convince Adm. Chester Nimitz that the emperor’s naval fleet was enroute to attack Midway Island. Unfortunately, Nimitz and his staff did not believe Rochefort. That is, until the codebreakers came up with a plan to change the admiral’s mind.

The Battle of Midway took place between 4−7 June 1942, and it was the turning point in the Pacific war. Six months after their December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and Col. Doolittle’s 18 April 1942 air raid on Tokyo, the Japanese navy under admirals Yamamoto, Nagumo, and Kondō planned a trap for U.S. aircraft carriers. The admirals hoped to lure the carriers to the Coral Sea where their navy would defeat the American navy and clear the way for attacks on Midway, Fiji, Samoa, and Hawaii. During the four-day battle, the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers and a heavy cruiser. The Americans lost the carrier Yorktown and a destroyer. After the U.S. victory, the Japanese were never able to recover from nor replace its loss of ships. Additionally, Yamamoto abandoned his plan to invade Midway.

Rochefort and his men devised a plan to convince Nimitz their intelligence was correct. They had the U.S. base in Midway send out a message that the Midway desalination system was failing. The Japanese intercepted the message and immediately provided desalting materials to their ships. After Rochefort’s team decoded this information, it proved to Nimitz that Midway was the target and Nimitz’s fleet was waiting to meet the Japanese flotilla. Rochefort and his codebreakers were vindicated. Unfortunately, Rochefort was never given credit for his role in the Midway victory despite being proposed for the Distinguished Service Medal. However, President Reagan posthumously awarded Rochefort with the medal forty-four years after the Battle of Midway.

Sometimes it takes a while to correct a wrong.

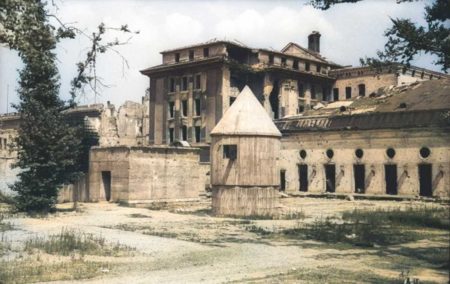

The Führerbunker

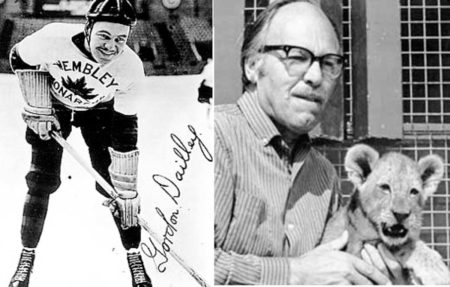

After driving into what was left of Berlin three days after Hitler killed himself in the Führerbunker on 30 April 1945, Maj. Gordon Dailley (1911−1989) and Ian Gordon, a British war correspondent and former hockey journalist, found themselves in front of the bunker entrance. There they found several empty jerry cans laying in a shallow trench. They knew Hitler was dead and assumed the fuel in the cans was used to burn the dictator’s body. While no one was looking, they took the cans as souvenirs.

Before the war, Canadian-born Dailley had been an ice hockey player who played for Great Britain in international competitions including the 1936 Winter Olympics. (Dailley’s national hockey team won the gold medal, and it was Great Britain’s only gold medal.)

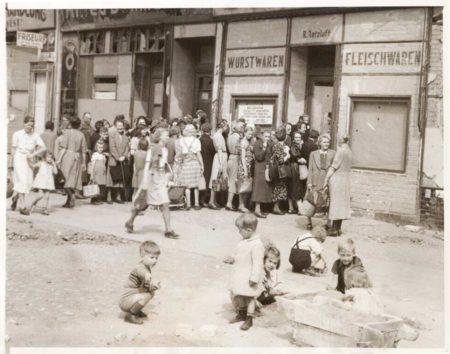

After their visit to the former Führerbunker, Dailley and Gordon drove through the bombed-out streets of Berlin. German citizens who survived the savage fighting by the Soviet soldiers and bombs were queuing in the streets for food that was being passed out by Allied troops. As they passed by one line, Dailley spotted a familiar face. Standing in line was a man whom Dailley faced nine years earlier on the rink at the Winter Olympics. He knew Rudi Ball was Jewish but how on earth did he survive the war?

Let’s Meet Rudi Ball

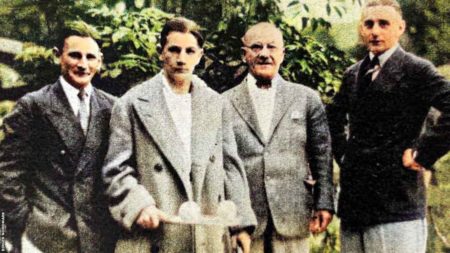

Rudolf Victor “Rudi” Ball (1911−1975) was born in Berlin to a wealthy Jewish textile merchant. His mother was a Lithuanian Christian and Rudi was the youngest of three boys. Rudi’s brothers, Gerhard (1903−1982) and Heinz (1907−1966), played hockey but Rudi did not show any interest in the sport but rather concentrated on academic studies. However, by the time he was fifteen, Rudi saw his brothers play against a Canadian, Blake Wilson. For some reason, Wilson’s style of play stoked Rudi’s interest in hockey and he decided to play. One thing concerned him: Rudi was only 5’4” and weighed 140 pounds. His father bought him skates and paid for private lessons with the Swedish hockey player, Nils Molander (1889−1974). As Rudi studied the game, he became convinced his size could be used to his advantage.

Professional Hockey

Seventeen-year-old Rudi Ball was selected to play for the Berliner SC second tier team for the 1927-28 season. He quickly became their top scorer. (He scored eleven goals in thirteen games.) Rudi was fast and agile with laser passes and accurate shots. Teammates, coaches, and opposing players soon realized that Rudi was special. The next year, Rudi was moved up to the club’s first tier team where he joined his brothers (Gerhard was the goalie) and his former tutor, Nils Molander, who was playing in his last year of professional hockey. Rudi played for Berliner SC (now known as Berliner Schlitschuh-Club) between 1928 and 1933 before joining EHC St. Moritz in the Swiss League (his brothers followed) for the 1933-1934 season. A year later, the Ball brothers moved to Italy and joined a Milan-based club. By 1936, the Winter Olympics were fast approaching and as a Jew in Nazi Germany, Rudi was on the outside looking in.

The Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws were enacted by the Nazis in September 1935. It consisted of two laws: “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor” and the “German Citizenship Law.” Initially, the laws were aimed at Jews but two months later, the Nazis expanded them to include Romani and Blacks. For international political reasons, Hitler did not enforce the laws until after the 1936 Summer Olympics. (There was a substantial American effort to boycott the games.)

The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor was about Hitler’s desire to sustain the purity of the German people (i.e., Aryan master race).

- Marriages between Jews and German citizens was forbidden.

- Extramarital relations between Jews and German citizens were forbidden.

- Jews were not allowed to employ German female citizens under the age of forty-five as household servants.

- Jews were forbidden to fly the German or Nazi flags.

- Punishment for violation of any law was prison with hard labor.

The German, or Reich Citizenship Law was enacted to prevent Jews from being German citizens.

- Only people with pure German or related blood could be a Reich citizen.

- Reich citizens would be issued a certificate confirming their status.

- Only a Reich citizen would be afforded full political rights.

One of the classifications outlined under the laws dealt with the definition of who could be considered Jewish. If a person had three or four Jewish grandparents, they were considered by the Nazis to be a “full Jew.” If a person had only one Jewish grandparent (out of four), they were considered to be a Mischlinge of the “second degree” compared to having two Jewish grandparents which would render them a Mischlinge of the “first degree.” A second-degree Mischlinge was not classified by the Nazis as a Jew according to the law. However, there was quite a debate about the status of a first-degree Mischlinge. Hitler finally ruled that someone with two Jewish grandparents would be considered Jewish if they practiced the Jewish faith or was married to a Jewish spouse.

It is likely Rudi would have been considered a first-degree Mischlinge (two Jewish grandparents on his paternal side).

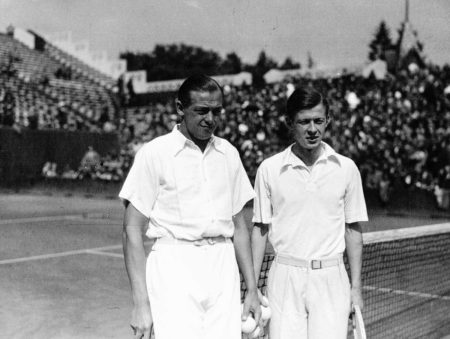

The German National Team and the 1936 Winter Olympics

Rudi and his brothers spent the off seasons in Berlin with their parents. When it came time for Germany to announce its national team, Rudi knew he would not be called up because of his religion. He was correct. However, the number one choice for the team, Gustav Jänecke (1908−1985) knew that without Rudi, the team had no chance of winning a medal like they did four years earlier. (Rudi had played in the 1932 Olympics when Germany took the bronze medal in ice hockey.) When Jänecke, Germany’s top defender, refused to play, the team backed him up. Despite Nazi threats, they held out until Hitler realized his team couldn’t compete without both Jänecke and Ball and it would look bad for the German team to sit out the games. So, he instructed his Reichssportführer, or “Reich Sport Leader,” Hans von Tschammer und Osten (1887−1943) to approach Rudi with their approval for him to play.

As an aside and a sad fact, the head of the U.S. Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage (1887−1975), was the featured speaker at a Nazi rally in Madison Square Garden prior to the 1936 Winter Olympics and revealed his antisemitism and racist views. As president of the International Olympic Committee between 1952 and 1972, Brundage earned an infamous reputation as a racist, sexist, and antisemite. He believed Jews and Blacks were not capable of performing at Olympic standards.

The Deal with the Devil

Rudi hated Hitler and the Nazis. However, he was passionate about hockey and especially playing with his teammates who supported him. When the Nazi officials confronted him about playing for the national team, Rudi felt obligated to play. However, he had one demand.

Rudi agreed to play in the Olympics under one condition. The Nazi government had to allow his family to leave Germany. It is likely this demand went all the way to Hitler for a decision. Rudi’s family would be given permission to leave if he played in the games. Amazingly, Hitler kept his promise and except for Rudi who stayed behind in Berlin, Leonard Ball and his family were allowed to emigrate to South Africa thereby escaping persecution and likely death in the extermination camps. (Why South Africa? The country had a large immigrant population of Germans.)

After the family was safely gone, Rudi kept his part of the deal and joined the national team. The government was funding the national program since hockey was considered to be the strongest and most popular winter sport in Germany. Hitler knew this and couldn’t stand the thought of winning any medal less than gold. At the time, Canada was the best team in the world and the one to beat in the Olympics.

On 5 February 1936 at the Olympiaschanze in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Hitler formally declared the games open in front of 50,000 spectators and a thousand competitors. The German hockey team faced tough preliminary group competition against the United States, Italy, and Switzerland. By beating Italy and Switzerland, it ensured the team moved onto the second group play. This time, the Germans had to play Great Britain, Canada, and Hungary to advance to the medal rounds. Unfortunately, Rudi was injured badly in the win (2-1) over Hungary but managed to score the winning goal. The team drew with Great Britain and lost to Canada without Rudi’s services as he had a broken shoulder, lacerated leg, and a lacerated forehead. Much to Hitler and Goebbel’s dismay, Germany did not advance on points.

Besides getting his family to safety, Rudi made the deal and played because he thought it was important to show the world (and Hitler) that Germans could stand together regardless of their heritage or religion. He wanted to show Hitler that Jews were not an inferior race and that the Führer’s concept of “racial superiority” was a falsehood. Rudi was proud of being German but embarrassed by the Nazi party’s ascension to power and racial theories.

Helene Mayer

Rudi Ball was only one of two German Jews who Hitler allowed to participate in the Olympic games held during 1936. The other was Helene Mayer (1910−1953), a German-born Jew considered to be the greatest female fencer. Mayer moved to the United States in 1935 to escape the tightening restrictions on Jews in Germany. (Helene would have been considered a first-degree Mischlinge.) Despite losing her German citizenship under the Nuremberg Laws, Helene was persuaded by the Nazis to return to compete for Germany in the 1936 Summer Olympics. (Hitler used her participation as evidence of Nazi tolerance toward Jews.) Helene won the silver medal in individual women’s foil. While on the winners’ podium, she gave the Nazi salute. After the games, Helene returned to America and finished a successful fencing career. In 1952, Helene Mayer settled in Germany but a year later, she died of cancer leaving very little evidence of her thoughts on her career and the real reason why she returned to Nazi Germany to participate in Hitler’s Berlin Olympics.

To this day, Helene’s salute on the podium remains controversial. She has been labeled a traitor and opportunist while some consider her story to be tragic. Helene’s family remained in Germany, and she later said that the salute was given to protect her family. (Her father died in 1931 and her brothers were sent to a labor camp where they survived the war.) Helene Mayer’s story is a complicated one whereas Rudi’s story is clear cut.

Return to Berliner SC

Rudi was forced by the Nazis to remain in Germany. He eventually returned to Berliner SC and played for the club until 1943 when Hitler suspended all sports. Although Rudi left the city at that point, there wasn’t a day that Rudi was afraid he would be picked up and deported. It is likely the Nazis kept him alive due to his celebrity status and to play hockey which they believed provided entertainment and morale booster to the public. Like other Germans, Rudi was forced to live on food ration cards and as the war neared its end, he suffered along with the other survivors of bombing and brutal Soviet treatment during the final weeks in Berlin.

“Hockey Owes Me Nothing”

Gerhard returned to Berlin shortly after the war ended and persuaded his younger brother to play hockey again but this time for SG Eichamp Berlin. By 1948, Rudi’s brothers convinced him to move to South Africa. Hockey was in its infancy in South Africa, but Rudi joined the Johannesburg Tigers for the 1949-50 season. The following year, Rudi moved to the Johannesburg Wolves and at the end of the season, at the age of forty-one, Rudi hung up his skates and retired. That is, until one last time when he played in the All-Star game between South Africa and Europe. Rudi scored four goals and the South Africa all-stars beat their European counterparts 10 to 4.

Rudi spent the remainder of his life in South Africa where he became a well-respected businessman. In 1970, a journalist asked Rudi if he thought hockey owed him more recognition. Rudi responded, “Hockey owes me nothing. I am the one that owes hockey. It saved me and my family from the Holocaust.” Unfortunately, not all of his family survived as he would learn several years after the war.

In 2004, Rudi Ball was posthumously inducted into the International Ice Hockey Hall of Fame.

So, what happened to the jerry cans that Dailley pinched in May 1945? Before he passed away, Dailley donated the cans to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

Next Blog: “The Rochambelles”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Frye, Wayne J. How Hockey Saved a Jew from the Holocaust: The Rudi Ball Story. Ladysmith, BC: Peninsula Publishing, 2011.

Haywood, Rob. Rudi Ball: The Jewish ice hockey star who represented and survived Nazi Germany. BBC, 7 June 2023. Click here to read the article.

Mogulof, Milly. Foiled: Hitler’s Jewish Olympian: the Helene Mayer Story. Bandon, OR: RDR Books, 2001.

Moorhouse, Roger. Berlin at War. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Rigg, Bryan Mark. Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers: The Untold Story of Nazi Racial Laws and Men of Jewish Descent in the German Military. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2002.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are on a cruise up to Alaska with two of our three children and their families. This is the cruise that was supposed to happen in 2020. Last year would have finally been the time but the grandkids weren’t vaccinated and that was one of the requirements for boarding the ship. So, we decided to take the cruise by ourselves. First time to Alaska and it was great. Never saw a black bear, bald eagle, or panther. That’s okay. We see those critters in Florida all the time.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Nicole C. for reading our blog, The Marvelous Madame Hamelin. Nicole pointed out a spelling error and as always, we’ll go back to the blog and correct it for future readers.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross