Dictatorships along with fascist and totalitarian governments expect their citizens to be subordinate to the state. This became evident after Hitler came to power in 1933 and demanded that law and order be upheld. It was expected that German citizens be law-abiding, obedient, and supportive of Nazism—this was called Gleichschaltung or, “make everything conform.” Protests, defeatism, criticism, and any other action detrimental to Nazism would be considered treason and would not be tolerated. As we will see, the Nazis created a system and a cult following which allowed the greatest abuses of justice, human rights, and war crimes in the 20th-century (no, I haven’t forgotten about Stalin/The Great Purge, Pol Pot/Khmer Rouge, and some of their notorious contemporaries). Children and young adults were beheaded for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. Women were executed for stealing tins of coffee. Special courts were established outside the boundaries of Germany’s “normal” legal system with judges and prosecutors who turned their courts into a circus. The most notorious and feared “ringmaster” was Roland Freisler.

Did You Know?

If you ever decide to visit Berlin (I’ve never been but it’s on my list), there are some World War II museums, memorials, and other historical sites that are off the beaten path for tourists. As you might know, Germany has outlawed anything having to do with the Nazi regime including making a Nazi salute. It’s only within the last twenty years that certain buildings or places have been identified with small signs signifying them as historical World War II sites. If a former Nazi building or site is identified this way, the official description must be as bland and unobtrusive as possible. One example would be the site of the former Führerbunker which today is a parking lot for apartment buildings. One of the three deportation points for Jews is Gleis 17 at Grunewals Station. It is a memorial to the victims shipped off to extermination camps such as Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Bebelplatz—formerly Kaiser Franz Joseph Platz—was the site of the first Nazi book burning on 10 May 1933. The Topography of Terror is an outdoor and indoor museum in Kreuzberg. Located on the site of the Gestapo and SS former headquarters, it chronicles the history of atrocities committed by the Nazis. These are just a few of the places you can visit. If you’re planning to visit Berlin and would like a list of these and more, please shoot me an e-mail and I’ll send you my list. (stew.ross@yooperpublications.com)

Let’s Meet Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler (1893−1945) was a fanatical follower of Hitler and the Nazi party. He was described by a fellow Nazi in 1927 as one of the party’s best speakers but “thinking people mostly reject him.” Freisler’s reputation at that point was that he was unreliable and unsuited for positions of authority. That would change after Hitler became the head of Germany in 1933.

Between 1933 and 1942, Freisler served in several positions within the Prussian Ministry of Justice and the Reich Ministry of Justice. His legal expertise, speaking skills, and dogged loyalty to the Nazi party made him the ideal person to enforce the tyranny of Nazism. Although Freisler was basically a loner without the political connections at the top of the Nazi hierarchy, he was invited to attend the January 1942 Wannsee Conference along with senior government officials and members of the SS. It was at Wannsee where final plans for the Final Solution were drawn up and Friesler provided the legal advice to support it.

Freisler had written papers outlining racial segregation theory and how to implement theory into practical situations. He supported new laws which punished Rassenschande or, race defilement—the Nazi term for sexual relations between an Aryan and a member of an “inferior race.” His writings and viewpoints strongly influenced the creation of the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. The original two laws were anti-Semitic and racially driven. The first, “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor,” outlawed marriage and sexual relations between Jews and Germans. What was a “German?” The second law took care of that. Entitled “Reich Citizenship Law,” it defined a Reich citizen as someone with pure German blood. Over time, the Nuremberg Laws were greatly expanded and provided the legal foundation for judges and prosecutors like Freisler to convict and execute German citizens, Jews, and other innocent people.

The Soviet Influence

While fighting on the Eastern Front during World War I, Freisler was wounded and captured by the Russians. As a prisoner, Freisler learned to speak Russian and developed an interest in Marxism. Repatriated to Germany around 1918, Freisler went back to Russia in the late 1930s to attend the Soviet Moscow Trials. These were a series of trials between 1936 and 1938 marking Stalin’s Great Purge of purported enemies of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The principal prosecutor (and in reality, judge and jury) was Andrey Vyshinsky (1883−1954).

Chief Prosecutor Vyshinsky believed one could be found guilty without committing a crime. He urged other prosecutors and judges to view defendants and the accusations in terms of class struggle rather than an individual crime. Vyshinsky would often write the indictments of the accused before the formal “investigation” was completed. However, what Vyshinsky was known for were his loud, demeaning, and vile outbursts aimed at the defendants. Freisler was an eye-witness to Vyshinsky’s tactics and as we’ll see, began to emulate Vyshinsky’s courtroom behavior.

The People’s Court

Shortly after the Wannsee Conference, Hitler promoted Freisler to president of the Volksgerichtshof or, The People’s Court. This was considered a “special court” and was established in 1934 because Hitler didn’t like the outcome of the Reichstag fire trial (all but one of the defendants were acquitted). The People’s Court was all about political crimes including black marketing, defeatism, treason, and work slowdowns (over time, the classifications of crimes expanded). Punishment was severe. Most of the defendants knew they would be found guilty even before walking into the courtroom—usually because their lawyer would tell them.

Besides acting as prosecutor, judge, and jury, Freisler added a fourth role to his job—that of recorder. In other words, Freisler was able to write the official record of the case without any oversight. He wore a blood red judicial robe while a large bust of Hitler’s head sat on a high pedestal behind his chair. Every session was opened with the Nazi salute. While Freisler modeled much of his behavior on Vyshinsky, the People’s Court and Freisler’s antics acted more like The Committee of Public Safety during the French Revolution period known as The Terror.

During Freisler’s tenure with the court, more than 5,000 death and life imprisonment sentences were handed out. These punishments accounted for approximately 90% of all his trial verdicts. He was especially harsh with anyone accused of resisting Nazi authority (i.e., treason). These trials were usually short in duration with Freisler yelling at the defendant while the verdict and punishment were always pre-determined. Typically, the defendants were not allowed to talk or consult with their attorney who normally sat apart from their “client.” Nor were the accused given the opportunity to present any evidence to defend themselves. The term “Kangaroo Court” would be very appropriate for the Volksgerichtshof.

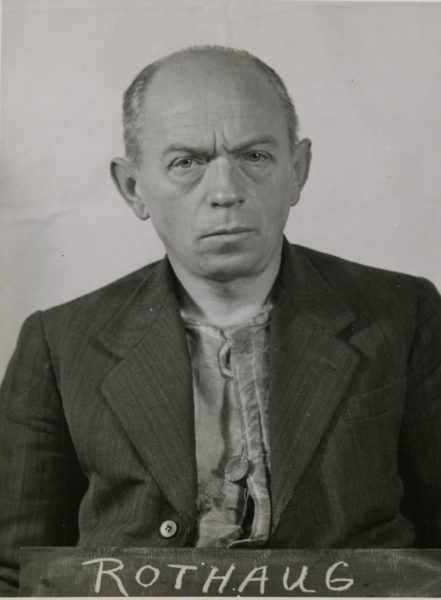

The Katzenberger Trial

Leo Katzenberger, an elderly businessman in the Nuremberg Jewish community, was accused of having an affair with one of his young tenants, Irene Seiler. This violated the Nuremberg Laws which prohibited sexual relations between Jews and Aryans. He was arrested on 18 March 1941 and put on trial for “racial defilement.” The Nazi judge and prosecutor was Oswald Rothaug (1897−1967) who sold tickets to the trial to prominent Nazis stationed in Nuremberg. No evidence was ever presented confirming the alleged affair. Katzenberger was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was guillotined at Stadelheim Prison in Munich on 2 June 1942. Irene received two-years in prison. This trial provided a sub-plot for the movie, Judgement at Nuremberg. Judy Garland’s movie character, Irene Hoffman, was based on Irene Seiler.

The White Rose

The White Rose movement began in June 1942 at the University of Munich. Members of the movement were students (and a few professors) from the university. They called for active opposition to the Nazi government but their activities were really limited to graffiti and the writing, publishing, and distribution of six separate leaflets over a seven-month period. The leaders, Sophie Scholl (age 21), her brother Hans (age 24), and Christoph Probst (age 23), coordinated the writing and distribution of the leaflets. A janitor at the university saw Sophie drop some leaflets off and contacted the authorities.

On 18 February 1943, the Scholls and Probst were arrested by the Gestapo and four days later, they walked into Freisler’s courtroom to face treason charges. Within thirty-minutes the trial was over. Unlike most of his trials, Freisler gave each of the condemned the opportunity to make a statement after being found guilty. Sophie’s statement was, “Where we stand today, you will stand soon.”

Several hours after making their statements, the three were guillotined at the Stadelheim Prison. There were several subsequent trials of other White Rose members with similar results. Today, there are numerous memorials around Munich and the university to Sophie and the White Rose Movement.

Helmuth Hübener

Helmuth Hübener was seventeen when he was arrested for treason by the Gestapo on 5 February 1942. He had been distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets around Hamburg. Helmuth had joined the Hitler Youth but became disenchanted when he watched the Hitler Youth participate in the destruction of Jewish properties and businesses during Kristallnacht.

Helmuth was tried in Berlin before The People’s Court. Again, it was a quick trial and he was found guilty. Two months later, the teenager was guillotined at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin.

20th July Plot Show-Trials

Probably the most famous set of show-trials which Freisler presided over were those for the accused plotters of the 20 July 1944 bomb attempt on Hitler’s life. The trial was filmed and Freisler can be seen and heard berating and yelling at the defendants. The first defendant was Field Marshall Erwin von Witzleben who was dressed in shabby, loose clothes with no belt. Freisler humiliated him by asking, “You dirty old man, why do you keep fiddling with your trousers?” Another defendant was Colonel-General Erich Hoepner whom Freisler addressed as a Schweinehund or, swine. Hoepner replied he was not a schweinehund to which Freisler wanted to know what zoological category the general thought he fit into.

Other trials of accused plotters took place in Freisler’s courtroom throughout August 1944. Almost all of the defendants met the same fate—hanged by piano wire on meat hooks in the special execution chamber at Plötzensee Prison.

Death of Roland Freisler

Freisler would hold court on Saturdays and it was one such morning on 14 February 1945 that an Allied bombing raid was conducted on Berlin. As the sirens went off, Freisler ordered everyone, including the defendant (really a prisoner), into the bomb shelter. Freisler stayed behind to gather his files when a bomb hit the court building and a concrete pillar fell on the judge, killing him instantly. The defendant was Fabian von Schlabrendorff, one of the co-conspirators of the 20th July Plot. As a result of Freisler’s death, Schlabrendorff was saved from a likely gruesome execution. Ironically, Schlabrendorff would go on to a successful post-war legal career as a judge in West Germany.

Roland Freisler is buried in Berlin with his wife and her family. After his death, his widow dropped the Freisler name and reverted to her maiden name, Russegger. His name was never engraved on the tombstone. Roland Freisler was never a very well-liked individual.

Post-War: The Judges’ Trial

The Judges’ Trial was the third in a series of twelve trials known collectively as the “Subsequent Nuremberg Trials.” (read the blog here.) There were sixteen defendants comprised of judges and prosecutors. The charges included implementing and furthering the Nazi “racial purity” program through Nazi laws. The trial lasted nine months. Ten defendants were found guilty, four were acquitted, one committed suicide prior to the trial, and one had his case declared as a mistrial. Of the guilty, four got life and the others received varying prison terms. By the end of 1956, every prisoner had been released under the West German belief that the actions by the ex-Nazis had been legal under the laws in effect at the time.

The Military Tribunal’s written statement about defendant Oswald Rothaug included the comment, “From the evidence of his closest associates as well as his victims, we find that Oswald Rothaug represented in Germany the personification of the secret Nazi intrigue and cruelty. He was and is a sadistic and evil man.” Rothaug was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment but released in 1956.

Natural death, suicides, or escape prevented the top-ranking judges, including Freisler, to be brought to justice. Many of the other approximately 570 judges and prosecutors of The People’s Court were never held responsible and many of them went on to post-war careers in the West German legal system.

The 1961 movie, Judgement at Nuremberg, is based loosely on the Judges’ Trial, Roland Freisler, and the case of Leo Katzenberger.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Kramer, Stanley (Producer). Judgement at Nuremberg. Roxlom Films/United Artists, 1961

If you haven’t seen this movie, I highly recommend you do.

Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra. New York: Random House, 2009.

Excellent book which talks about the resistance movement in Berlin by German citizens (and one American woman). We’ll talk about Die Rote Kapelle or, Red Orchestra in our next blog. It was one of the largest German resistance movements during the war and I hope you enjoy reading it.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We’re getting closer to moving into our new house. It should be about three weeks. In the meantime, I’m trying to get seven blogs written since we’ll be busy with the move and then we begin our heavy traveling season.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I hope you all enjoyed the blog on the cemetery symbolism as well as the humor. Rhea S. particularly liked the Alfred Packer story. As always, thanks Rhea for your kind words of support. If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross

The text interchanges the surname between Friesler and Freisler. These are two different names and should be corrected and harmonized.

Thank you William for pointing out these spelling errors. Despite several sets of eyes reading and re-reading the content, errors do slip through. Hope you enjoyed reading the blog in spite of the mis-spellings. STEW

Excellent summary.

I am now writing a book on “The Devil’s Advocates: Fouquier-Tinville, Vyshinsky and Freisler” (the parallels are astounding!)

What are your sources, please, concerning the relationship between Freisler and Vyshinsky, in particular F’s trip(s) to Moscow during the Moscow trials?

Truly,

E.D.

Hello Emmanuel; Thank you for contacting us. Unfortunately, I don’t have much to go on with respect to sources about Freisler’s journey to Moscow. It seems that trip did two things. Vyshinsky’s courtroom antics likely influenced Freisler who seems to have adopted similar methods. Second, after returning to Germany, Freisler was accused of being a Communist and this didn’t sit too well with Hitler (but he eventually got over it). The theme of your book is very appropriate. I agree that the parallels between these three men are astounding. It just goes to prove that it can happen again and again if the circumstances are right. STEW

Do you know which year was that trip?

Thanks!

Hi Emmanuel; Our trip to Nuremberg and the courtroom was in late October 2017. STEW

Im finishing my presentation on Freisler and Vyshinsky. Do you what year Freisler went to see Vyshinsky in Moscow?

Thanks!

Hi Emmanuel; Good to hear from you again. The year was 1938. I have sent you several sources confirming the year. Glad to hear you are finishing your book. STEW