Many of you may remember the blog I wrote in March 2018 (yes, it has been four years) about the story of top turret gunner, T/Sgt Hilton Hilliard (1920−1985), and his adventures in France and Germany after his B-17 heavy bomber was shot down in May 1943 on a bombing run to the U-boat pens at Saint-Nazaire, France (click here to read the blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo). After parachuting into the French countryside, Hilliard and one other crew member, left waist gunner T/Sgt George Smith (1921−1983), began their quest together to evade the Germans and return to England.

I wrote the blog about Hilton Hilliard after learning the story from his daughter, Ann. After the blog was published, I heard from several relatives of the men who survived the downing of the “Queen of the Skies.” Greg Smith, son of George Smith, was one of those who contacted me, and I have followed Greg’s journey that began almost forty years ago to piece together his father’s wartime “adventures.” (Remember, most of the men, including George Smith, did not talk about their wartime experiences after returning from the war.)

Today, Greg will share with you his father’s story that he has been able to assemble through meticulous research and frankly, some luck. Here is a narrative by the son of a World War II left waist gunner.

Did You Know?

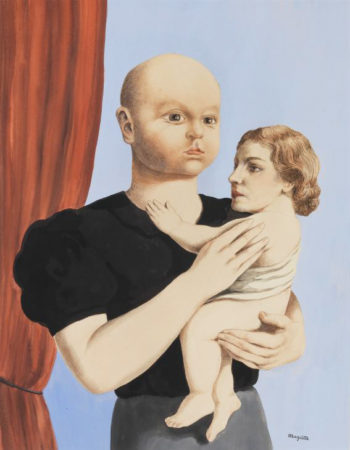

Did you know that a well-known French resistance fighter and her family financially supported the struggling Surrealist artist, René Magritte?

Suzanne Spaak and her husband, Claude, befriended the starving Belgian artist during the period when Magritte was earning a living by designing wallpaper. In exchange for financial support, Magritte gave his benefactors paintings of surrealistic themes (many of the topics were suggested by Claude). Soon, the walls of the Spaak’s Belgian home were covered with surrealistic images, the likes of which, no one had ever seen. In 1936, Claude convinced his friend to paint a Spaak family portrait. It was called L’Espirit de Géométrie, or “Spirit of Geometry.” It is a creepy painting of a mother holding an infant. The problem: the head of the mother was Claude and Suzanne’s four-year-old son, Bazou and the infant’s head is Suzanne. I think Dalí would approve.

The Spaaks moved to Paris in 1937 while Magritte stayed in Belgium where he continued to struggle. After the Nazis invaded Belgium, Magritte fled to France and stayed with the Spaak family. Suzanne became involved with the French Resistance and was captured by the Gestapo (click here to read the blog, Something Must Be Done). Unfortunately, she was executed several days before Paris was liberated. Claude remarried and used the family collection of Magritte paintings to support his lifestyle until his death in 1990.

A rare Magritte painting was recently sold for US$79.75 million.

X Marks The Spot: Top Secret Touchdown

South of Bakersfield, California, the day is cold and windy. Parked on the edge of a dirt airstrip used by military aircraft for emergency landings, my Grandmother Nell and Aunt Glendora are looking skyward. Having driven all night from Los Angeles over the old Ridge Route in my aunt’s 1932 Model A Ford Coupe, they’ve made this pilgrimage with the help of gasoline ration cards contributed by friends and neighbors. (By 1942, just about everything was being rationed for the war effort.)

It’s now or never. Due to the loss of large numbers of heavy bombers in the air war over Europe, my dad’s unit is being redeployed from Hawaii to England. Of course, this is top secret information. Air crews were informed that all furloughs and over-night passes had been canceled. As the story goes, shortly after landing at Moffat Field near San Francisco my aunt received a collect telephone call. Before he hung up, my dad gave her directions where and when they could meet the next day. Exactly how this clandestine rendezvous was arranged with the pilot and co-pilot is not known. Supposedly, they’d received orders to proceed non-stop to Beeville, Texas and report for aerial gunnery practice.

True to his word, dad made a grand appearance aboard a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. They heard it first, then caught sight of it coming down out of the clouds. After making a thundering low pass and circling once, the plane touched down, then taxied over toward their car and stopped nearby. According to Aunt Glendora, a small hatch door opened and out he jumped wearing a handsome fleece-lined leather flight jacket and grinning like the “Cheshire Cat” in Alice in Wonderland. Their reunion was short, five minutes tops. All four turbo-charged 1200 horsepower Wright Cyclone radial engines were kept running ready for takeoff.

Naturally, some tears of joy and sorrow were shed in the process of saying hello and goodbye. Before dad left, Grandma Nell hugged and kissed him one last time. After that, Aunt Glendora handed him a cardboard box full of homemade oatmeal and raisin cookies to share with the rest of the crew. As it turned out, neither one of them would see him again until the war was over three years later.

As my Aunt Glendora finished recalling these events, she laughed and said my dad made them both swear they wouldn’t stand around and watch his plane until it disappeared. “It’s bad luck”, he said. Then she told me, “George was very superstitious, so Nell and I both crossed our hearts and promised him that we wouldn’t. And we didn’t. I’ve never really thought about it until now, but it must’ve worked. It was a miracle he made it back in one piece.”

Bait, Hook, Line, and Sinker

This conversation took place in 1985. I can still hear Aunt Glendora’s voice clear as a bell. Although I didn’t know it then, that was only the beginning. I swallowed the bait, hook, line, and sinker. Obviously, there was a whole lot more to this tale, but I was basically clueless and didn’t know where to start. Dad never said much about the war. As a result, I’d only heard a few bits and pieces of the puzzle that would be important later on.

Of course, it would’ve been easier if I’d been able to ask him what happened after he flew away that day. Sadly, that wasn’t possible. The man I’d stuck to like glue when I was a kid wasn’t around anymore. A victim of the American Tobacco Company, he was only 62 years old when he smoked his last Chesterfield cigarette and died of lung cancer in 1983.

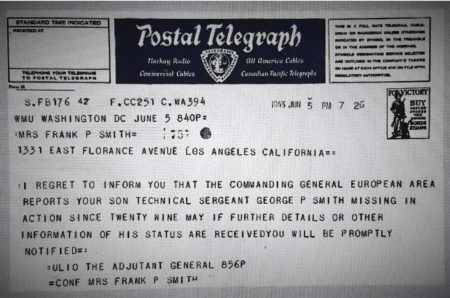

As a veteran of a foreign war in Vietnam, it took me a while to decide to try and sort out the facts of dad’s military service myself. Thankfully, I had Aunt Glendora’s help. Before she passed away herself, she gave me an old suitcase full of dad’s U.S. Army Air Corps records that included a Western Union Telegram notifying my grandmother that her son’s plane had been shot down on May 5, 1943 and that he was listed as “Missing in Action.”

She also gave me dad’s silver airman’s wings and a framed, life-like, pencil sketch that was drawn by Harold Rhoden when they were both POWs at Stalag 17B in Krems, Austria. How he ended up there after gunnery training at Beeville was still a mystery at that point.

A Treasure Trove of Service Records

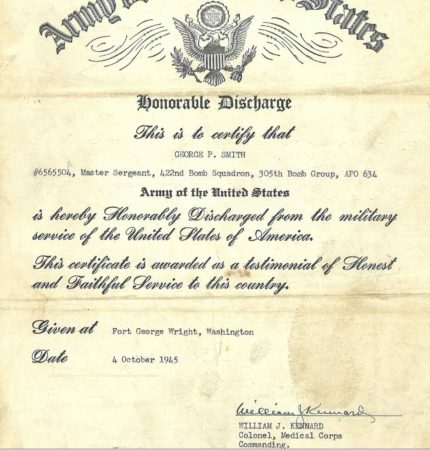

One of the first things that came to light when I opened the suitcase Aunt Glendora had given me was a sturdy brown envelope containing dad’s Honorable Discharge Certificate dated October 4, 1945. The only thing I’d known before that was that he had been a member of the 8th Air Force. This document confirmed that he’d served with the 1st Division Air Wing, 305th Bomb Group, 422nd Squadron.

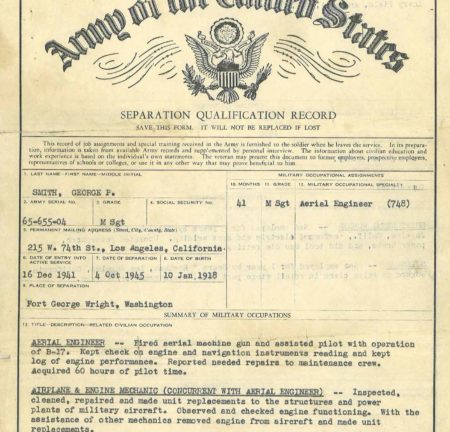

I discovered several more things I never knew when I found the “Separation Qualification Record.” The first was the date of dad’s active-duty enlistment⏤December 16, 1941. This was only nine days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. The second was that in addition to being a machine-gunner, he was also a qualified flight engineer. The third, and most surprising of all, was that dad had acquired sixty hours of pilot time at the controls of a B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber.

More Questions & More Answers

When I started this project, the internet was in its infancy, so I wrote letters and made phone calls trying to track down people who might be able to answer my questions. It was easier back then because many of the veterans who had survived WWII were still alive. I also read several books and watched documentary films about the air war in Europe. Later, I used the internet to do most of my research. That’s when I finally found what I was looking for thanks to a Belgian citizen by the name of Édouard Reniere. Édouard also referred me to the Saint-Nazaire Memorial Association that maintained records of American B-17 bombers and their crews that were either listed as missing, captured, or killed in France.

It was Édouard who emailed me the tail number and squadron identification letters of dad’s B-17 Flying Fortress (JJ-Z Serial No. 42-29531). He also sent me a list of the crewmembers. These men are noted as follows: Pilot: Lt. Marshall R. Peterson Jr. (Service Number O-791493), Co-pilot: 2nd Lt. Harold E. Bentz (Service Number O-733590), Navigator: Lt. Lawrence F. Mandelberg (O-791493), Bombardier: 2nd Lt. F.R. Perrica (Service Number O-13070741), Radio Operator S/Sgt John J. Freeman (Serial Number 32345263), Top Turret Gunner: T/Sgt. Hilton G. Hilliard (Service Number 34198474), Bottom Turret Gunner: Peter P. Milasius (Serial Number 36335879), Right Waist Gunner: T/Sgt Clayton P. Matthews (Serial Number 34168544), Left Waist Gunner: T/Sgt George P. Smith (Serial Number 06565504), Tail Gunner: S/Sgt Salvadore S. Tafolya (Serial Number Unknown). While this was obviously a big step forward, unfortunately, Facebook wasn’t invented yet.

Dad’s War Story Starts to Unfold

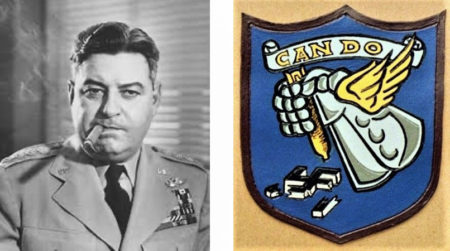

The 305th Bomb Group was a part of the U.S. Army 8th Air Force and began forming in England in October 1942. Commanded by Colonel Curtis LeMay (1909−1990), it was one of the most decorated units of World War II. Dad’s squadron, the 422nd was based at RAF Chelveston airfield, approximately seventy miles northwest of London. Its first bombing raid was on 12 December 1942. The target was the railroad yards and steel plant at Lille, France. Other raids soon followed and included the U-Boat construction wharves at Wilhemshaven, Germany; the industrial factory-complex at Hamm, Germany; the aircraft manufacturing plant at Bremen Germany, and the shipyards at Vegesack (near Bremen, Germany) and Rotterdam, Holland.

Although I wasn’t able to pin down the exact date when dad’s plane finally arrived from the United States, this is likely to have occurred sometime in late February or early March, 1943. Two trans-Atlantic routes were flown by B-17 bombers and their crews heading for combat duty in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). The northern route went from Newfoundland over to Iceland and ended in Ireland. The southern route went from Florida down to Brazil, then over to either the Azores or Morocco in North Africa. From there, they would refuel and fly directly to England. Due to hazardous winter weather conditions along the northern route, many aircraft made the longer trip. Dad took the “scenic” southern route. The only reason I know this is because I can recall hearing him telling a funny story about how the radio operator bought a little monkey for a mascot in Marrakech. After they took off for England, he said the thing went absolutely “ape-shit” and tore up a bunch of charts, maps, and code books.

However, it was no laughing matter when they landed at RAF Chelveston airfield in England. They were replacements. Just more “fresh meat” for the grinder. During the early part of 1943, the majority of air crews never finished the 25 combat missions required in order to be rotated stateside to become training instructors. The odds were only 1 in 3 for getting that lucky. There were a couple of reasons for this. Often, they had no protection by American fighter aircraft. Daylight raids also made the tight bombing formations perfect targets for German anti-aircraft batteries. Those who weren’t killed, wounded, or shot down and never seen alive again were few and far between. By the war’s end, the 8th Air Force had lost over 6,000 heavy bombers which included both B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators. The death toll was staggering. More than twenty-six thousand airmen were killed. Another twenty-one thousand were casualties.

B-17 JJ-Z Serial No. 4229351 and its crew only flew 9 combat missions before they were shot down. According to French eyewitnesses, the crash site was behind a hill named “La Cîme de Kerchouan” near a small village in the Bretagne region of France.

Luck Runs Out Over the Target

The official military description of the loss of dad’s plane during the bombing raid on the U-boat submarine pens at Saint Nazaire is very brief. It only says, “Crashed after being hit by flak and attacked by enemy fighters.” Referred to as “FLAK CITY” by bomber crews because of the intense and accurate anti-aircraft fire, the 422 Squadron had been there at least twice before and they probably dreaded the thought of going back again. Edward Jablonski, a U.S. Army Air Corps historian also noted in his own description of the early raids on Saint Nazaire . . . “The German fighters too were murderously fearless in their attacks. They no longer attacked from the stern. Their new approach was to drop in from the 12 o’clock position, then fly head-on straight into the bomber formations with their guns blazing. Because of the tremendous closing speed of both aircraft, an error in judgment increased the chances of mid-air collisions.” Click here to watch the video “St. Nazaire U-boat Pens and Fangrost Roof.”

Making it even tougher, the approach to the target was over the Bay of Biscay and on this raid, as before, the bombers were intercepted by several large groups of enemy fighters, including Messerschmitt Me 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, before they reached the French coastline. As a result, they not only had to fight their way in, but when they got there, they had to endure flying through a virtual hailstorm of exploding 88 mm anti-aircraft artillery shells that zeroed-in on the leaders of the formation. Heavily damaged planes that escaped being shot down over the target, suddenly became easy targets themselves as they began to drop out of formation and were attacked once again by enemy fighters on the way back.

That’s what happened to dad’s plane. Apparently, it took several anti-aircraft flak hits in close succession during the bombing run, one of which instantly killed the right waist gunner, T/Sgt. Clayton Mathews. Dad was also wounded in the hip and knee, but not too seriously. Rapidly losing altitude with No. 4 engine on fire, the pilot and co-pilot did their best to keep their badly shot-up plane flying level until they finally lost control of the aircraft and it went into a steep spiraling nosedive.

Stew’s Note: At this point, I will jump ahead in Greg’s story. This portion of his father’s story (i.e., evasion, capture, and POW status) is available to read on my blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo (click here to read).

Persistence Pays Off Again

I don’t claim to be a licensed private investigator, but I’ve “learned by doing” that if you keep looking long and hard enough, there’s always a chance that you’ll find something that’s either been lost, missing, or somehow overlooked by others. And once this type of connection is made, it often doesn’t stop there.

Over the years, I’ve taken time to periodically search the internet for new information concerning dad’s war story. Recently, this has resulted in a couple of truly amazing discoveries. In 2018, I found a photo of dad’s plane being worked on by the ground crew at Chelveston field. I just happened to stumble upon it while doing a Google search of the serial number of dad’s plane: 4229351. The photo was posted on a German website: B-17 Bomber Flying Fortress – The Queen of the Skies.

A friend of mine, Stewart Ross, forwarded it to the U.S. Army Air Corps Museum in Georgia for verification. They weren’t too surprised. They said it had probably been taken by a British spy. (click here to read the blog, Agent Jack, “M” and the Fifth Column.) Apparently, the German Luftwaffe kept track of all arriving American heavy bombers, including those that were shot down or destroyed.

The Chances Were Slim to None

Thousands of B-17s were lost in the ETO and only a very small number were actually photographed when it happened. Like most replacement aircraft, B-17 JJ-Z Serial No. 4229351 had no nose art. It was just one of a large group of 154 heavy bombers that attacked the German submarine pens at Saint Nazaire, late in the afternoon on May 29, 1943.

As fate would have it, a trained cinematographer was not only present, but close enough to take 16 mm color footage of dad’s plane in a steep nosedive with crewmen bailing out. Although the identity of this aircraft would remain unknown until 2019, this 17-second film clip would become a part of Captain William Wyler’s film, “The Memphis Belle,” that documented one of the first U.S. 8th Air Force B-17 crews to survive 25 combat missions by 1943. It was released in 1944. Filmed scenes also appeared in the Hollywood movie, “12 O’clock High,” that was released in 1949 and seen by millions of Americans. Watch this video (click here) and at the 4:00 minute mark, you will see dad’s plane going down.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this until 2021. That’s when I checked the German website again and discovered a high-resolution, enlarged photo of dad’s plane with its 422nd Squadron JJ-Z lettering clearly visible on the fuselage. Posted opposite it was a very detailed and realistic painting by an artist named Steven Ingraham.

I Couldn’t Believe My Eyes!

But that was only the tip of the iceberg. I did a quick search for Steve Ingraham and gave him a phone call. Bingo again. He answered it himself. Apparently, the co-pilot’s son had beat me to the punch a few weeks earlier and had purchased a couple of prints. As a result, he wasn’t too surprised when I identified myself as the son of George P. Smith, the left waist-gunner. I was anxious to buy one too.

It only occurred to me later to call Steve Ingraham back and ask him more questions. It soon became apparent that I’d finally found someone who had the answers to solving a mystery that meant as much to him as it did to me. I wanted to know the facts as he knew them. Steve told me that he’d seen William Wyler’s footage many times before and that he’d always wanted to try to identify this Flying Fortress. What finally made it possible was seeing a 4K color restoration of the original documentary film footage released by Kino Lorber in 2019. It was called “The Cold Blue.” (Click here to watch, this is a trailer of the documentary and at 01:20 minutes, dad’s plane can be seen going down with two men parachuting out.) He also said that it was a group effort and encouraged me to watch it myself. As soon as I hung-up, I ordered it from Amazon. It was a truly amazing experience when I finally recognized B-17 JJ-Z spiraling past Capt. Wyler, or one of his fellow cinematographers, at 20,000 feet above the coast of France.

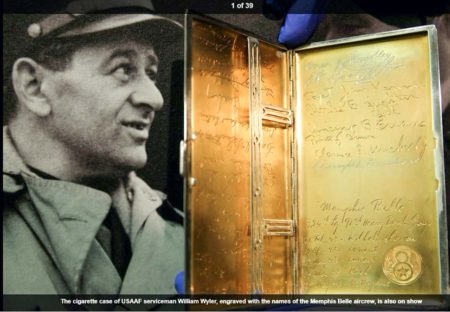

After that, I began trading emails with Steve and talking with him frequently. He was always happy to oblige and gave me Harold Bentz’s (co-pilot) report describing 88 mm flak damage to the hydraulics in the number four engine that resulted in a “runaway propeller” and loss of control of the aircraft. He also sent me picture of a gold cigarette case that contained an engraved record of all the missions Capt. William Wyler and his group of cinematographers had flown. It confirmed his fifth and final filming took place at Saint Nazaire on May 29, 1943. The last piece of the puzzle was a Google Earth image I decided to check myself. Steve had told me that it perfectly matched a brief glimpse of the French coastline near the Loire River estuary seen in the original documentary footage of B-17 JJ-Z being shot down. A retired engineer with an eye for small details, he was right again.

Luck Always Runs Out In The End (Stew’s Comment)

Both Hilton and George were very lucky men. They were captured by the Gestapo while wearing civilian clothes. The out-of-uniform airmen could have easily been executed by the Nazis as spies but fortunately, they were eventually deported to a Luftwaffe prisoner of war camp. After liberation, Hilton and George returned to a civilian life. Neither of them lived beyond the age of sixty-five. While cigarettes may have claimed the life of George Smith, the two years as POWs certainly took a toll on each man’s health and likely contributed to their early deaths.

Stew’s Notes

I edited Greg’s story for several reasons. First, I wanted to streamline the narrative (in other words, I have only so much room). Second and most important, I thought his journey of discovering his father’s wartime story was very interesting and I didn’t want to overshadow it by getting “into the weeds” with respect to George’s adventures in France and Germany. For general background on the B-17, crew, and the fateful ninth mission, please click here to read the blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo.

How many sons and daughters, grandchildren, nieces and nephews of Allied soldiers have done what Greg has pursued? Since most of the men never discussed their wartime experiences, their relatives were left to piece together “the best years of their lives.” Greg has done an admirable job of investigating, researching, and documenting his dad’s contribution to eliminating the Nazi threat to the world.

Greg, your father would be very proud.

★ Learn More About the WWII American Heavy Bomber ★

Ambrose, Stephen. The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany 1944-1945. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

American Air Museum in Britain. Click here to visit the web-site. Click here to see the aircraft page.

Army Air Corps Library and Museum. Click here to visit the web-site.

Bartlett, Sy and Beirne Lay, Jr. Twelve O’Clock High. New York: Harper & Brothers (1948; hardcover) and Bantam Books (1949; paperback).

Goldwyn, Samuel (producer). The Best Years of Our Lives. Samuel Goldwyn Productions, 1946.

Hotton, Randy and Michael W.R. Davis. Willow Run (Images of Aviation). Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2016.

Matzen, Robert. Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. Pittsburgh: GoodKnight Books, 2019.

Mullen, Cassius and Betty Byron. Before the Belle. Conneaut Lake, PA: Page Publishing: 2015.

National Archives. Click here to read the story of the B-24 Liberator Hot Stuff.

Puttnam, David and Catherine Wyler. Memphis Belle. Warner Bros., 1990.

Snyder, Steve. Shot Down: The True Story of pilot Howard Snyder and the Crew of the B-17 Susan Ruth. Seal Beach: Seal Beach Publishing, LLC, 2015.

Sturges, John (producer). The Great Escape. The Mirisch Company, 1963.

Valant, Gary M. Vintage Aircraft Nose Art. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1987 (Zenith Press⏤reprint, 2002).

Wilder, Billy (producer). Stalag 17. Paramount Pictures, 1953.

Zanuck, Darryl F. (producer). Twelve O’Clock High. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, 1949.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Many thanks to Greg Smith for sharing his father’s wartime experience with us today. Greg is a graduate of the University of California at Santa Barbara and is a retired city planner. He is an experienced river guide and outfitter who leads four-wheel drive trips throughout the Mojave Desert and Great Basin.

Thanks to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Fred M. and Nicole C. for contacting us regarding our annual blog, May 5, 1945 (click here to read). Fred agreed that a tissue comes in handy listening to the young musician. Nicole mentioned that she has a commemorative coin from the early 1990s. I’ve asked Nicole to send me an image of the coin to share with all of you.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross