One of the most effective resistance activities during World War II was the establishment of escape and evasion lines (click here to read the blog Escape Lines). These were elaborate, sophisticated, and clandestine routes set-up to guide downed airmen and escaped POWs back to England.

Today’s blog offers you the opportunity to learn about a former British military intelligence agency dedicated to supporting the escape and evasion lines as well as the Possum Line and its Belgian founder, Dominique Edgard Potier.

Did You Know?

Did you know that four sitting United States presidents have been assassinated? Robert Todd Lincoln (1843−1926), the eldest son of Abraham Lincoln, was nearby when three of the presidents were assassinated. Lincoln served in the Union army on Gen. U.S. Grant’s staff and he later became secretary of war under presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. One of Lincoln’s last public positions was an appointment by Benjamin Harrison as minister to the Court of St. James’s in the United Kingdom.

Lincoln was “hanging out at the White House with some friends” (his words) when news arrived that his father had been shot. He went to the house where President Lincoln was taken across the street from the Ford Theater. He stayed with his father until the president died the next morning on 15 April 1865. During the evening of 30 June 1881, Lincoln met with President Garfield and several other cabinet members when the president asked for his recollection of the events of his father’s assassination. Less than forty-eight hours after that discussion took place, President Garfield was shot while Robert Lincoln stood nearby. Three months later, the president died from an infection of his wound. Lincoln went on to become president of the Pullman Car Co. and in 1901, President William McKinley invited Lincoln to join him at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. When Lincoln arrived by train in Buffalo, he was given the telegram informing him that McKinley had been shot. He rushed to the president’s bedside and was encouraged by McKinley’s progress. However, President McKinley succumbed to infection and died on 14 September 1901. He was the third United States president to have been assassinated and Robert Lincoln was a bystander to all three.

After that, Lincoln said, “There is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present.” He never accepted five separate invitations to run for president or vice-president.

British Directorate of Military Intelligence Section 9 (MI9)

Many of us are aware of two well-known British intelligence organizations: MI5 and MI6. During World War II, the British War Office created the secret MI9 department with its mission of assisting POWs to escape and to help military personnel (primarily downed Allied airmen) evade capture behind enemy lines in Axis-controlled countries. Escape and evasion lines were established in many of the occupied countries, but the best-known lines originated in Belgium and France. As Allied bombing increased in 1942, the evasion lines became an integral part of resistance activities and perhaps, one of the riskiest. MI9’s headquarters was located at the Shean Block within Wilton Park in Buckinghamshire, England.

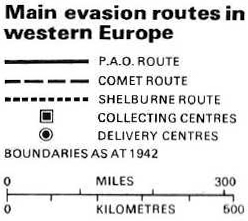

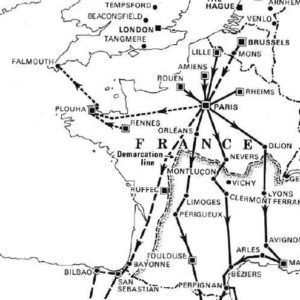

Famous evasion lines included the Pat O’Leary line (click here to read the blog, The White Mouse), Comet, a Belgian line run by Andrée de Jongh, the Burgundy line, and the Shelburne line (created by MI9). Regardless of the country of origin, most of the evasion lines ran through Paris where the men were either taken to Switzerland or most often, south over the Pyrenees mountains into Spain and then onto Gibraltar where they flew back to England. Each line had hundreds of “helpers.” (More than half of the estimated 12,000 helpers were women.) Helpers were responsible for finding safe houses, providing false documents, and guiding the evaders and escapees to “neutral” Spain or Switzerland. Unfortunately, most of the evasion lines were eventually compromised by traitors or German double agents (click here to read the blog, The Rasputin of the Abwehr and here to read the blog The Last Train Out of Paris).

After the war, MI9 was disbanded but some sections (e.g., Intelligence School) survived through its sister agencies. One of MI9’s legacies was the “Q” department, an agency devoted to creating devices to aid the evaders. It was the model used by Ian Fleming in his fictional James Bond series. (Click here to read to the blog, Explosive Rats.)

Dominique Edgard Potier

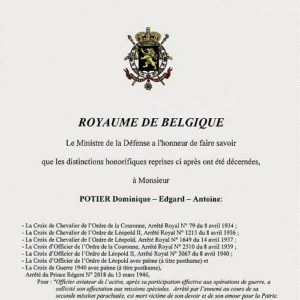

Edgard Potier (1903−1944) was the second of four children by Alphonse Potier and Leopoldine Damin. Edgard attended military schools and joined the Belgian 8th Artillery Regiment in 1928 before becoming a pilot in the Belgian air force and earning his degree in aeronautical engineering in 1935. By May 1940, he became Capitaine-Commandant Potier (equivalent to a flight lieutenant in the RAF) of the 7e Escadrille in the Belgian air force flying a Fairey Fox bi-plane. On 25 May 1940 while on a mission to deliver an urgent message to Belgian Command, Potier’s Fairey Fox was shot down by a British destroyer over the English Channel near Calais. Rescued from the sea by the destroyer, Potier was taken to Dover but returned to Dunkirk the next day to complete his mission. Potier returned to his Belgian unit and was captured by the Germans. Released in August 1940, Potier was unemployed until May 1941 when he joined the Belgian government. During this time, Potier became active in the underground resistance. Potier left Belgium in November 1941 and entered Vichy France. In mid-February 1942, Potier fled occupied France and successfully made his way to England.

Potier arrived in London in March 1942 and joined the Belgian section of the RAF. However, the RAF considered him too old to fly (i.e., at the age of 39) and after refusing a noncombatant position, Potier joined MI9 reporting to Airey Neave (1916−1979) who considered Captain Potier as “. . . one of the bravest of all the agents under my charge”. After training as a landings officer, Potier was ready to go into action in the occupied countries by mid-1943.

Potier’s mission was to establish two MI9 evasion lines in Belgium (Mission Martin) and France (Possum). The objectives for Potier and his team were:

- Organize the recovery of evading RAF personnel.

- Organize landing sites, in the north of France, for airlifting the evaders.

- Organize escape lines to these landing sites.

- Organize shelter for the evaders, where they can wait to be airlifted or where they will be able to stay safely for several days with provisions, clothes, etc.

- Produce false identity documents.

- Establish one or more escape lines down to St. Sebastian or Barcelona in Spain.

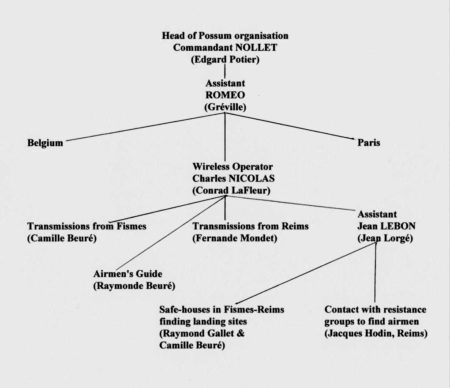

On the night of 15/16 July 1943, Potier (nom de guerre: Commandant Nollet) and his second-in-command and wireless operator, Conrad LaFleur (nom de guerre: Charles Nicolas) parachuted from a RAF Halifax onto a landing site at Suxy, near Florenville in the Belgian Ardennes (i.e., Operation Manningtree). It was a blind drop meaning there would be no reception party.

Possum (Latin for “I Can”)

Potier landed hard and sprained his ankle. However, the two men walked about six kilometers (3.75 miles) to Chiny, Belgium. Over the next month, Potier began to build his network while headquartered in Fisme (Marne) with operations in the surrounding districts as well as the city of Reims, France.

Besides his wireless operator (LaFleur) who transmitted frequently from the homes of Camille Beuré (Fismes) and Mme Fernande Mondet (Reims), Potier recruited Jean Lorgé (nom de guerre: Jean Lebon) to act as a lookout for LaFleur. Raymonde Beuré was responsible for guiding the airmen while Raymond Gallet (1896−unknown) and Camille Beuré (1896−unknown) scouted safe houses and suitable landing sites. (Raymonde was Camille’s 20-year-old daughter and she never accepted payment for her work.) Jacques Hodin furnished the majority of downed airmen through his contacts with other evasion/escape lines.

Between August and December 1943, Possum successfully conducted three separate operations (Brasenose, Magdalen, and Magdalen II) repatriating eleven airmen: one RNZAF, eight USAAF, two RAF, and one Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent (i.e., Pierre Geelen, an agent with the compromised SOE Physician/Prosper Circuit and known to the Gestapo). On 16/17 November 1943, Captain Potier returned by Lysander to England (Magdalen II)⏤it was the same Lysander that delivered Lucien Dumais and Ray Labrosse to France for the purpose of establishing the Shelburne escape line. A month later, on 20 December, Potier parachuted back into France (Operation Brasenose III) for the last time. Like most escape lines, Possum was eventually compromised and betrayed.

Betrayal

In the early evening on 29 December 1943, LaFleur was transmitting from Mme Mondet’s residence located at 161, rue Lesage when the Gestapo pounced. Raymonde Beuré was acting as the vigie, or lookout when she saw several cars stop outside the house. A confrontation ensued but LaFleur and Beuré managed to escape and rendezvoused with Potier and Hodin. Unfortunately, Beuré left her purse inside the house and in it were papers, her photo, and a card with the addresses of people who worked for Possum. Also in her purse was the key to one of the two rooms she rented at Hôtel Jeanne d’Arc located at 36, rue Jeanne d’Arc. The Gestapo had all they needed.

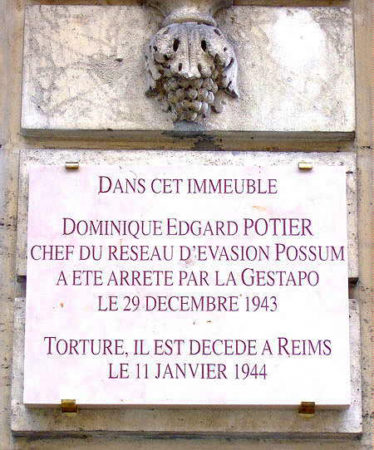

Raymonde Beuré’s fiancé, Raymond Jeunet, was arrested by the Gestapo after exiting a train in Reims late in the evening on 29 December. He had a photo of his fiancé and admitted knowing her. The following day, the Gestapo took him to the hotel on rue Jeanne d’Arc where the owner or concierge recognized Raymonde and identified the room she rented. For some inexplicable reason, Potier decided to stay in the hotel room and was arrested. (Initially, the Gestapo thought he was LaFleur.) Captain Potier was taken to Gestapo headquarters, interrogated, and tortured. Days later, he threw himself off the prison internal walkway in an attempt to commit suicide. Edgard Potier died of his injuries on 11 January 1944. Three days after the raid on the rue Lesage residence, the Gestapo arrested fifty-eight members of Possum. Most of them were sent to prisons in Reims and Paris and then deported.

Our story does not end here.

Aftermath

By the end of October 1944, the Germans were gone and a formal inquiry by a French military tribunal was made into who betrayed Possum. Eight people were condemned to death for collaborating with the Nazis:

- Raymonde Jeunet, née Beuré

- Raymond Jeunet, husband of Raymonde

- Roland Jeunet, brother of Raymond−on the run during the trial

- André Jeunet, brother of Raymond

- Colette Jeunet, sister of Raymond

- Camille Jeunet, father of Raymond

- Marie-Louise Jeunet, mother of Raymond

- Louise Jeunmet, wife of Roland

As a result of numerous requests for intervention on behalf of Raymonde, an investigation was initiated. The investigation resulted in a written report by Sub-Lieutenant Bruder (the “Bruder Report”) and is dated 6 December 1944. Click here to read the report.

Based on circumstantial evidence, it was initially thought that Raymond Jeunet betrayed Possum. However, it was finally determined that the Gestapo raid on the house at 161, rue Lesage was a result of denunciation by Possum’s Jean Lorgé (1916−unknown). Potier’s arrest was blamed on Roland Jeunet (Raymond Jeunet’s brother and Raymonde’s brother-in-law) who had hoped to find LeFleur in the hotel room. (A letter from Roland to the Gestapo was found offering his services to the Germans.) In return for setting him free, Raymond Jeunet disclosed information to the Gestapo that led to the arrests of other Possum résistants. While some of Raymonde’s actions came under scrutiny, the investigation concluded “that Raymonde Beuré did not deliberately betray her country.”

The results of the investigation commuted half the sentences including Raymonde’s death sentence. The death penalty was upheld for Marie-Louise Jeunet and two of her sons. Roland Jeunet was eventually captured and executed in September 1945.

Lt. Conrad LaFleur (1916−1979) was repatriated to England and survived the war. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct medal (Britain) and the Croix de Guerre (France). Mme Mondet (1897−1945) was deported to KZ Ravensbrück where she died. Her daughter, Simone, refused to accept the U.S. Medal of Freedom awarded to her mother. Raymond Gallet and Camille Beuré were each awarded the U.S. Medal of Freedom. Jean Lorgé was deported to KZ Buchenwald and was liberated in April 1945.

★ Learn More About the Possum Escape Line ★

Clutton-Brock, Oliver. RAF Evaders: The Complete Story of RAF: The Complete Story of RAF Escapees and Their Escape Lines, Western Europe, 1940−1945. London: Grub Street Publishing, 2009.

Bourne-Paterson, Maj. Robert. SOE in France, 1941−1945. Yorkshire: Frontline Books, 2016 (originally published as ‘The “British” Circuits in France, 1941−1944’ by Maj. Bourne-Paterson).

Eisner, Peter. The Freedom Line. New York: Perennial, 2005.

Fitzsimons, Peter. Nancy Wake. Sydney: HarpersCollinsPublishers, 2011 (originally published in 2001).

Foot, M.R.D. and J.M. Langley. MI9: Escape and Evasion 1939−1945. London: Biteback Publishing, 2013 (originally published 1980).

Fry, Helen. MI9: A History of the Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

Hore, Peter. Lindell’s List. Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2016.

Janes, Keith. They Came from Burgundy: A study of the Bourgogne escape line. Leicestershire: Matador, 2017.

Pearson, Judith L. The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2005.

Purnell, Sonia. A Woman of No Importance. New York: Viking, 2019.

Treadwell, Terry C. Great Escapes. Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2008. (Chapter Seven.)

Fred Greyer’s Possum Escape Line: Click here to see a map.

Click here to read the Bruder Report.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are wrapping up our preparations for the June trip to Europe. We will spend one week in Paris and the following week in the U.K. and Scotland. The purpose of our trip to France is to visit the former KZ Nazweiler-Struthof, the only concentration camp located on French soil. Raphaëlle will accompany us for the two-day “mini-trip” (south of Strasbourg) as well as our day trip to see the Pantin and Bobigny rail stations. The camp and departure points for the deportees will be featured in volume two of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? We are looking forward to seeing Raphaëlle and her family once again as well as visiting other friends in Paris, England, and Scotland.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Jon R. for contacting us regarding the blog, Camp King (click here to read the blog). Jon’s father was a guard at the camp and wanted to know where he could acquire any records about his father’s service. Unfortunately, there was a fire in July 1973 at the National Personnel Records Center and almost eighteen million military personnel files were destroyed. It appears the files for Jon’s father were among those destroyed.

Bianca L. wanted to know what “literary references” I used for my comment about the black ribbon painted around the neck in portraits of French Revolutionary victims. My comment was based on our visit to a French château where we saw two portraits of young men of nobility who had been guillotined. Each had a black ribbon painted posthumously over their necks. It was explained to us that after the revolution, many families painted the black ribbons to signify the fate of the person in the portrait.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Todd Lincoln’s life was largely a mystery to me. Another great “DID YOU KNOW? The MI-9 Escape & Evason network story was well documented and thorough as usual. It’s a tribute to these brave men and women. Their sacrifices should not be forgotten. Thanks again, Stew.

Thanks Greg. Glad you enjoyed it. STEW