I’d like to welcome Dr. Marianne (née Seidler) Golding as our guest blogger this week. Rather than me rattling on and on, I will ask Dr. Golding to introduce herself.

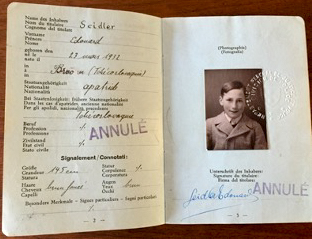

“I am a French and International Studies professor at Southern Oregon University. I am the daughter of Édouard Seidler. I started to research my father’s past in the summer of 2019, using letters, photographs, and various documents such as refugee cards and police reports. Édouard, his mother, and sister, fled their native Brno (Czechoslovakia) in 1939, at which point they became refugees in France and for the latter part of the war, my father and his sister, Lisette, lived in Switzerland. After the war, Édouard returned to France where he lived until his death in 2010.

“As I started to research my father’s journey, I was very fortunate to discover Bernard S. Wilson’s novel on the internment camps in the south of France, as well as the events of the Retirada. I knew nothing of this exodus from Spain to France, even though my maternal grandfather (Arthur Madden) had fought with the International Brigades and died in the last battle of the Spanish Civil War. Thanks to Bernard, I found out a wealth of information that both spiked my interest in that historical period and helped me find out more about my family. Bernard also introduced me to Dr. Ron Friend, one of the many children saved from the internment camp of Rivesaltes by Irish heroine, Mary Elmes.” (Click here to read the blog, Miss Mary: The Irish Oskar Schindler.)

Did You Know?

Did you know that a Polish teenager’s diary sat untouched in a bank vault for seventy years before the family could bear to read it? Renia Spiegel was fifteen when she began her diary in September 1939 (the month the Germans invaded Poland). As a Jew, Renia was forced into hiding and her diary describes the bombings as well as the disappearance of her friends from the ghetto. On 7 June 1942, she wrote in her diary the following:

Wherever I look, there is bloodshed. Such terrible pogroms. There is killing, murdering. God Almighty, for the umpteenth time I humble myself in front of you, help us, save us! Lord God, let us live, I beg You, I want to live! I’ve experienced so little of life. I don’t want to die. I’m scared of death. It’s all so stupid, so petty, so unimportant, so small. Today I’m worried about being ugly; tomorrow I might stop thinking forever.

One month later, hiding in an attic, Renia was discovered and shot dead where she stood by several German soldiers. She is referred to as the Polish Anne Frank. (Click here to read the blog, The French Anne Frank.)

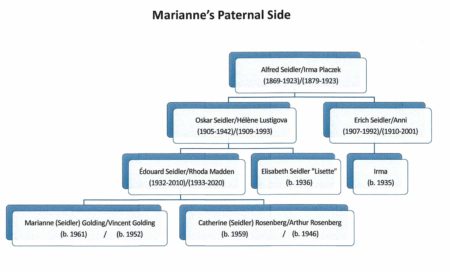

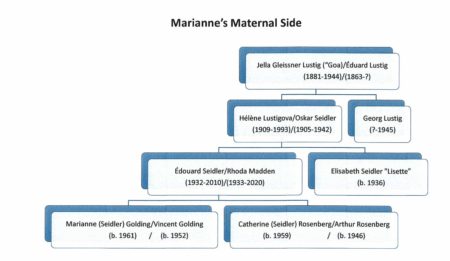

Seidler Family Tree

Édouard Seidler (1932−2010)

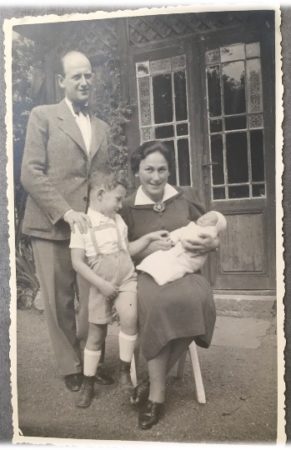

My father, Édouard Seidler, was born on March 23, 1932 in Brno, Czechoslovakia. He lived on the second floor of a house on Tivoli street (today, Jiraskova street); his cousin Irma lived on the third floor with her parents. As a safety precaution, to pass for Christian during the war, Irma’s parents had her do her first communion in Italy, where they had escaped.

I was able to locate the house whose street name had changed to Jiraskova when I spent a few days in Brno to find some information about my father. My father had also looked for it with his mother around 1990.

In April of 1939, a month after the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia with the approval of the France and Great Britain (Treaty of Munich), Édouard’s mother obtained exit visas to France. The Czech were only too happy to provide Jews with visas! My father, my aunt Elisabeth (Lisette), and grandmother Hélène/Helena/Lena were able to leave the country, in hopes of a better and safer future in Paris.

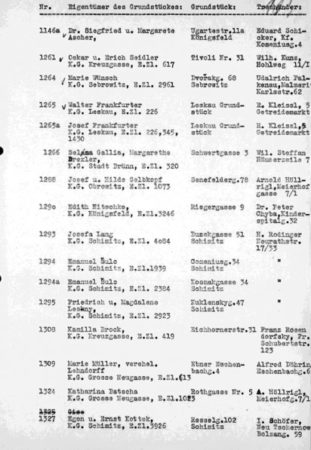

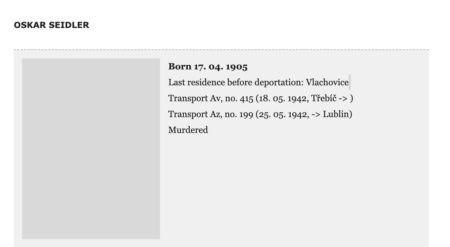

My grandfather never made it out, in part because he didn’t sell his house or his clothes factory in time, but also because he felt he hadn’t done anything wrong that would justify reprisals from the Germans. When Oskar Seidler did sell his house and factory to non-Jews in 1941, it was for a price well under its worth (see # 1261 in the image below for the house sale). That type of transaction defines Aryanization! By that time, it was too late to leave the country. He was sent to a labor camp in 1941, then to Terezín, and finally to Lublin where he was murdered in 1942.

Once my grandmother arrived in Paris, she and the children stayed with some Czech friends on rue de la Pompe in the 16th arrondissement.

“In Paris we were welcomed to begin with by a couple of friends at rue de la Pompe (very close to the place where we have been living since the 1990s), which however did not prevent my mother from searching for work. She found it quickly enough, as a fashion dress designer in a store, tasks very similar to those which had been her responsibility at the core of her husband’s business. She could not however accept new responsibilities while remaining in sole charge of her children. She therefore sent us off to Switzerland on temporary permits, my sister into a Valais family from Brig, I myself near Neuchatel.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

After the war, Hélène would eventually run the children’s clothes factory Petit Bateau in Agen and later become the director of Tricosa in Paris. My father returned to Paris in 1940 after a long stay in Switzerland – where Lisette was to remain a few more months – but when the Germans invaded the north of France in June 1940, Édouard and Hélène relocated to the south (the “free zone”).

“I returned alone from Switzerland at the end of several months. When I rejoined my mother in Paris, the German danger was becoming pressing. My mother had managed, at that time, to make contact with some old friends from Czechoslovakia, Paul Thorz in Paris, and the Freunds in Agen. It was therefore decided that she and I would leave with the former for the southwest of France, where we would join the others.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

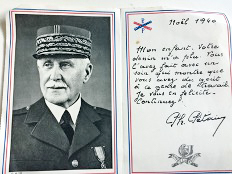

Édouard attended the primary school Joseph Barra in Agen. All school children were made to draw a picture for Pétain in December of 1940, and all the children received the exact same thank you card, mailed (and maybe addressed by the school staff?) to their school!

Before Hélène started working at Petit Bateau, the family lived in near poverty, my father growing and selling garlic to the locals, and my grandmother knitting socks for the rugby team!

“We had to move into a building without running water. I used to fetch water from out in our street, with a jug. Of course it was only possible to relieve oneself at the end of the garden, in the shelter of a foul booth, taking care to preserve in passing the precious plantings of the mini-garden; my garlic, which I was going to sell, was remarkable.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

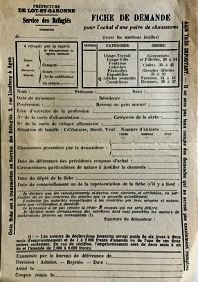

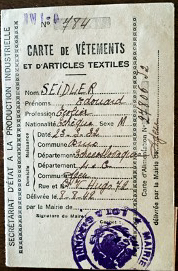

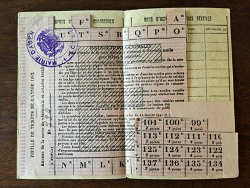

Lack of food and clothing made daily life for most people very difficult. Rationing concerned food and clothing as well as soap and other necessities. One had to get authorization to buy certain items before receiving a coupon for the item.

In August 1942, a month after the Vel d’Hiv roundup in Paris, the French (more precisely, Vichy general secretary to the police, René Bousquet) offered to hand over thousands of (foreign) Jews from the “free zone” to the Germans in exchange for more independence of the French police. In addition to the 10,000 or so Jews already interned in camps, he promised to round up another 20,000. The French conducted three days of raids, August 26-29 when 6,500 Jews were arrested, a number well under Bousquet’s earlier estimate. Luckily, like many other Jews, my grandmother (Hélène) was tipped off about the raids that were to take place and was able to escape with Lisette. Édouard had left for summer camp, most likely in one of the homes run by Pétain’s Secours national (a social services organization).

“During the summer of 1942 – I was little more than ten years old – I was sent away to a holiday camp managed by my school at Bagnères de Bigorre, in the Pyrénées. Then the local leaders of the Resistance learned that the French police were preparing a round-up of Jews at Agen, and that I would be arrested myself at Bagnères. Mr Löwinger, from a group of Austrian origin, working at the Grange munitions factory at Agen, advised my mother to leave with my sister as quickly as possible for his apartment on the boulevard Pelletan. At the same time, the Rabbi of Agen enlisted a young girl 16 or 17 years old, and asked her to search for me at Bagnères, with this urgent recommendation: ‘Get him out of there, take him no matter where, but don’t bring him back here.’

“My mother fled on her bicycle, installing Lisette on her padded seat at the back. She came back again in the evening to collect some clothes, to the fury of Löwinger. After that, Paul Valton, the owner of her factory, offered her hospitality. When the police came by, there were no birds in the nest. On the other hand, a tenant in our building, wishing no doubt to be well-regarded by the men of the Militia, informed the policemen that I could be found at Bagnères, in my school’s holiday camp.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

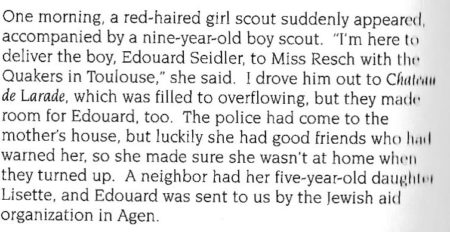

My father goes on to explain how he was taken away from the camp, and how Alice Resch Synnestvedt rescued him:

“The telephone worked well. Warned from Agen, the director of the camp asked me to stay where I was, even though my comrades were going for a walk. And I was able, with my young girl companion from Agen, to leave the area by train in the direction of Toulouse, a few minutes only before two Militia men presented themselves in vain to the director of the camp. On arrival in Toulouse my companion and I left the station and wandered around the vicinity. There could be no question of returning to Agen. What else to do? Above the entrance to a building, my companion perceived the acronym of the Quakers. She had a vague recollection of them, and in particular, it was fixed in her mind that the Quakers have a mission to ‘do good.’ She therefore entered the building in my company.

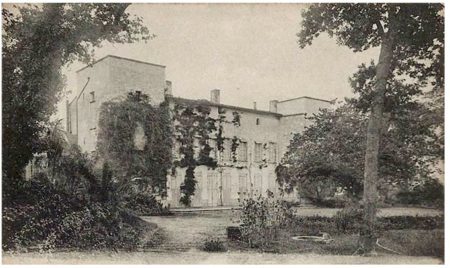

“We were received by a young lady, rather slight and slender, a Norwegian named Alice Synnestvedt. She listened to our story, discharged the young Agen girl who had escorted me, and conducted me to the Château de Larade in a suburb of Toulouse, full to bursting with Spanish children, sons and daughters of republican parents who were opposed to Franco. Several days later, my sister came to rejoin me at Larade.

“In Toulouse, my mother was successively a servant in a middle-class family living close to the Germans, and a waitress in a bar where her knowledge of the German language attracted a number of soldiers from the occupying troops. Someone had obtained papers for her in the name of Gilberte Marty, according to a customary procedure: when a young girl married, it was common for her identity papers to be passed on to any married women who might have need of them.

“My mother was carrying out the function of barmaid when she was caught in a round-up in Place du Capitole and questioned by a customer of her bar, to whom she had to show her (false) papers. She offered him the papers in the name of Gilberte Marty, who remained as my ‘aunt’ throughout the war. “These papers are worthless”, said the man “Don’t come here again!” And, satisfied by her assurance, he let her leave.

“Gilberte Marty left her bar, which had become too dangerous, found a position as children’s nurse at the Massardy household, in a suburb of Toulouse, and was not caught in any subsequent round-up.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman).

The house in which my grandmother stayed for two years in the suburb of Toulouse is the Château l’Armurier where socialist Léon Blum had been arrested in June of 1940 for “treason” to France. Hélène was able to spend some Sundays at Larade with her children. Her last visit to Larade was on the day Édouard and Lisette, accompanied by Alice, set off for the Swiss border at Annemasse. That eventful journey is described in detail in Alice’s war journal, The Highest Mountains: A Memoir of Unexpected Heroism In France During World War II, edited and published at the request of her friends in 2005. This is my father’s shorter version of the story:

“Alice Synnestvedt led my sister Lisette and me towards Annemasse, at the Franco-Swiss border, in March 1943. (Editor: Records reflect the actual departure as late January 1942 with arrival in Switzerland in early February.) A French border guard had been bribed not to oppose our passage. Alas, the service rotation had been changed, and our man was not there on the day stated. So I tried in vain to enable us both to crash the border by fording a narrow river which marked the boundary and also, I think, by a little bridge over the same river. Not succeeding in thus crossing into Switzerland, I returned to Annemasse, where I was able to re-establish contact with Alice, whilst she was preparing to return to Toulouse. “I had believed the matter was closed. Discovering that it was not, I aged around fifty years at that moment” she would say afterwards.

“We broke through the frontier the next day. Perfectly briefed, we held each other by the hand, Lisette and I, and passing in front of the customs building ran towards Switzerland. Alas my sister, aged then less than seven, thought it a good idea to let go of my hand, to stop, and to stare at the (good) border guard who, pretending to chase us, was himself rooted to the steps of his hut. I shouted to Lisette to rejoin me. It took several appeals before she would resume her course, and for the border guard also to resume his. We ran across some fifty metres before arriving at a little bridge, which we crossed without any difficulty. We were in Switzerland.

“Detained by the Swiss police, we replied to the questions which they asked us, after which a small van conducted us to the Carouge camp, near the centre of Geneva. A few days later, and at the end of several interrogations, my sister rejoined at Brig the Gerber family who had already welcomed her in the Valais, whilst I myself was ‘adopted’ by some friends of my family, the Kuntz, at Lausanne.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

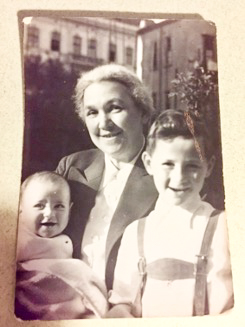

Ensued four years of life for Edouard and Lisette in separate homes in Switzerland, until the summer of 1945 when the children returned to Agen and reunited with their mother. Unfortunately, none of the family members who had stayed in Czechoslovakia survived.

“I only found out later how a major part of my family had disappeared. My father went first. They transported him, I believe, to the immediate extermination camp at Auschwitz in Poland (it was actually Lublin). My grandmother Jella Lustig was quickly taken to Theresienstadt (i.e., Terezín), in Czechoslovakia. This was one of the less formidable camps. In her misfortune, she had the good luck that her son George, my mother’s brother, found himself there as well. An engineer, he was employed in the camp as a baker, which for a long time allowed his mother to allay her hunger. George was going to end up by marrying Anda, who survived and settled herself much later in Sao Paulo, in Brazil. My grandmother died a prisoner, as did George, who would disappear in an extermination camp a few days (someone told me ‘a week’) before the end of the war. The camp where he was seen for the last time was, I believe, Buchenwald.” (Bouquin Addendum, Édouard Seidler. Translated by Michael Belman, 2009).

Click here to visit the holocaust.cz web-site.

Stew’s Postscript

Terezín was a concentration camp located 30 miles north of Prague. It was turned into a Jewish ghetto in 1940 with internees from Czechoslovakia, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, and Denmark. It was considered part of Theresienstadt, a “camp-ghetto.” Theresienstadt was used as a transit camp, ghetto-labor camp, and “settlement,” or assembly camp. Of the 150,000 Jews sent there, fifteen thousand were children and less than 150 of them survived. The primary deportation sites were the extermination sites, KZ Treblinka and KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Marianne mentions her grandfather, Oskar, was murdered at Lublin. The Lublin main camp was also known as Majdanek, one of the Nazis’ primary extermination camps.

La Retirada was the retreat of about 440,000 Spanish civilians and soldiers in late January/early February 1939 to France. It was the largest influx of refugees ever known in France. The French government was taken by surprise and unprepared as well as being hostile to the refugees.

The American Friend’s Service Committee (AFSC; Society of Friends; Quakers) were instrumental in providing food, clothing, and shelter for thousands of refugees in the Vichy, or unoccupied zone. The AFSC operated in French internment camps, hid Jewish children, and assisted Jewish and non-Jewish refugees with immigration and resettlement in the United States. The Quakers worked in the camps around Marseilles, Toulouse, and Montauban. Mary Elmes and Alice Resch Synnestvedt worked under the auspices of the Quaker organization in their attempts to save the lives of hundreds of children. For its efforts during the war, the AFSC was awarded the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize.

Norway’s Alice Resch Synnestvedt (1908−2002) and Mary Elmes (Ireland) were honored as “Righteous Among the Nations.” Alice was honored in 1982 while Mary did not receive recognition until 2013 on a posthumous basis. Alice’s wartime exploits in saving the lives of the children were well-known and validation for her nomination was relatively easy. However, Mary never spoke of her activities, and it wasn’t until Bernard S. Wilson uncovered the facts that Ronald Friend, a child saved by Mary, was able to approach Yad Vashem to nominate Mary Elmes. (Click here to read the blog, Miss Mary: The Irish Oskar Schindler).

Édouard Alfred Seidler was a lieutenant in the French Air Force and honored with decorations such as Knight of French Legion of Honor and Officer National Order of Merit (France). He was the director of the daily French newspaper, l’Équipe for many years. He finished his career as a respected French freelance journalist and received numerous professional awards. Édouard’s writing centered around automobiles and racing. He was a member of the Guild Motoring Writers (London), French Association Automobile Press, Racing Club France, president of the “Jury de la voiture de l’année” (the yearly car award), and Association des Journalistes Sportifs. *

Reproduction of images is prohibited without the permission of Marianne Golding.

★ Learn More About Alice Resch Synnestvedt ★

Megargee, Geoffrey P. (editor). Foreword by Elie Wiesel. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933−1945. Volume I, Part B. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Megargee, Geoffrey P. (editor). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933−1945. Volume II, Part A. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Rees, Evan. Sketches of the Horrors of War. “The Journal of the Friends Historical Society.” Volume 67, 2016 (Pages 42 through 50). Synnestvedt, Alice Resch. Over the Highest Mountains: A Memoir of Unexpected Heroism in France during World War II. Altadena: Intentional Productions, 2004.

Wilson, Bernard S. Bernard’s Journey to Discover the Irish Schindler. Click here to read the blog. Dr. Golding has loosely translated Bernard S. Wilson’s novel, Grandad’s Journey: A Holocaust Story⏤(L’Énigme de la photo jaunie, or “The Enigma of the Faded Photo”). Both the original and the adaptation are soon to be published. Click here to visit her website.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I were invited by Dominic Lee to a special one-day showing of selected pieces by Sir William Orpen (click here to read the blog, The Racer, the Spy, and the Erotic Model). Dominic inherited the “Orpen Research Project” archives from his friend, Chris Pearson who sadly passed away in 2021. Among these pieces include an illustrated letter by Sir William where he depicts a photographer with himself and his French lover Yvonne Aupicq at the Longchamp Races, Paris 1919. The collection also includes a drawing of the French serial killer, Henri Landru (click here to read the blog, The Parisian Bluebeard is Guillotined).

The exclusive exhibition is in Dublin, Ireland and unfortunately, we will not be able to attend. If only it was several weeks later, we would be in the U.K. and would definitely make the trip to Dublin to attend. Here is Dominic’s video of Orpen’s artwork: click here.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Stephen F. for letting us know we made a couple of spelling errors in two blogs (refer to blogs Sex Toy and Other Père Lachaise Neighbors [click here] and The Theft of the Mona Lisa: Louis Lépine [click here].) We’ve made those corrections. We don’t shy away from people pointing out my mistakes. It only makes us better. Thanks, Stephen, for your kind comments about our blogs as well as pointing out the errors.

Catherine F. contacted me with a question regarding the Béthune group/escape line (click here to read the blog, Escape Lines). Unfortunately, I have not run across that particular group, nor could I find it with some limited research. However, I did put her in touch with a well-known expert on World War II escape lines. This gentleman is the son of the MI9 officer who founded the Possum escape line. Perhaps he will be able to answer Cathi’s questions.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Thanks for posting this Stew. A truly remarkable and well documented story in so many respects.

Thanks Greg. It’s just one out of millions of stories. Unfortunately, most have been lost to history. STEW