Serge Klarsfeld did an exhaustive study of the French children who were deported to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau and other concentration camps during the German Occupation of France between 14 June 1940 and 25 August 1944. The number of deported children (i.e., under the age of eighteen) totaled 11,146. He estimated that less than three hundred returned. His book (see below in “Recommended Reading”) is quite lengthy at 1,881 pages. The motivation behind writing the tome was to create a memorial to the children by recording images of the young victims rather than allowing them to slip into history as mere statistics and a footnote. Klarsfeld appealed to the families and friends to send him photographs of the children who were deported. Approximately two-thirds of the book are these photographs and, in many instances, a short description of the childrens’ fates.

I will center our discussion today on the children who survived. However, most of the stories do not end well as parents and siblings often perished at the hands of the Nazis. Click here to watch the video clip French Jewish Children for the Holocaust.

Did You Know?

Did you know there is a Paris métro station by the name of Parmentier? It is line 3 on the Right Bank in the 11th arrondissement (terminus points: Pont de Levallois Bécon and Gallieni). Located between stations République and rue Saint-Maur (one stop from Père Lachaise cemetery), the platform is decorated with antiquities, tile frescoes, and riveted copper plates. The primary decoration is . . . the potato. The métro station was named after August-Antoine Parmentier (1737−1813), a health food promoter, scientist, and marketer. He was quite the Renaissance man. He learned Latin at the age of thirteen and was a pharmacist. His passions were botany, agronomy (field crop production and soil management), and nutrition. As a soldier during the Seven Years War, Parmentier was captured and imprisoned by the Prussians. While in prison, he survived by eating potatoes and developed a taste for them. After his release and return to Paris, Parmentier began marketing potatoes (and the benefits of eating them) to the French. Prior to this, the potato was considered to be animal food (similar to the way the Dutch felt about corn). Another hurdle for Parmentier was that prior to 1785, French “social media” claimed eating potatoes caused leprosy. Parmentier was a clever fellow. He began planting potatoes and posting “guards” around the fields to give the appearance that the potato was valuable. That did the trick. People began to steal the plants as the guards looked the other way. He began to invite all his famous friends and celebrities (including Benjamin Franklin) to dinner where he served potatoes in various ways. Now, Parmentier felt the time was right and he presented King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette with potato blossoms. The king declared the potato to be acceptable and the rest is history. I wonder if the king’s last meal included potatoes.

Enjoy your pommes-frites the next time you visit France. They are especially good at restaurants in the village of Versailles.

The First Convoy

The first convoy leaving France for a concentration camp departed 27 March 1942. It held 1,112 French Jews who had been arrested by the French police in the May and August 1941 roundups. They were naturalized as well as foreign-born Jewish men. They had been interned at the detention camps in Drancy, Compiègne, Pithiviers, and Beaune-la-Rolande. With the exception of one, all of them were adults. Israël Knaster (1924−1942) was seventeen. He was the first and the only child on the train headed to Auschwitz. Upon arriving at Auschwitz on 2 April, the survivors of the trip were given tattoos numbered 27533 to 28644⏤Israël was number 28771. Only twenty-two of the deportees on Convoy #1 survived. Israël was murdered on 19 April 1942. (Click here to read the blog The Auschwitz Tatooist.)

Union Générale des Israélites de France

The Union générale des israélites de France (UGIF) was the National Jewish Council created in November 1941 to coordinate Jewish social and philanthropic organizations in France. Although SS-Hauptsturmführer Theodor Dannecker (1913−1945) demanded the UGIF be established, it was Xavier Vallat (1891−1972), head of the Vichy Commissariat général aux questions juives (CGQJ), who created the UGIF. Even though the UGIF appeared to be a benevolent organization, over time it became a “mouse trap” for French Jews. They were required to register with the UGIF and provide all sorts of information including where they lived. The Nazis and French police ultimately used this information during the roundups and arrests of the Jews.

One of the functions that the UGIF provided was establishing orphanages for the children whose parents had been deported. Responsible for the “Jewish Question,” or ridding France of its Jewish population, Dannecker was replaced in July 1942 by SS-Obersturmführer Heinz Röthke (1912−1966). Berlin and SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann (1906−1962) did not believe Röthke was aggressive enough in deporting French Jews so SS-Hauptsturmführer Aloïs Brunner (1912−2010?) was assigned to the Drancy internment camp in June 1943 and put in charge of the deportations. Brunner, a thoroughly despicable person, met and exceeded all expectations. Over the next year, he filled the trains to capacity and when they were short, he hunted down the children in the UGIF facilities to meet his quotas.

Pierre Laval and Vichy

Pierre Laval (1883−1945) was the head of the Vichy government. The Nazis did not require the deportations of children under the age of eighteen, pregnant women, or women with babies. After his reinstatement as prime minister in April 1942, Laval and his Vichy chief of police, René Bousquet (1909−1993) decided to deport the children. Laval’s comment was “it is not of interest” to me. It’s speculated that this decision was made because they didn’t know what to do with orphaned children and second, Laval didn’t want the children growing up and finding out that the government was responsible for the murder of their parents. After the liberation of France, Laval was executed after being found guilty of treason. (Click here to read the blog Time Magazine’s ‘Man of the Year’ is Executed.) Bousquet was tried and found guilty but the sentence was dropped. In 1989, Klarsfeld filed a complaint against Bousquet and in 1991, an indictment was issued. Three weeks before Bousquet’s trial was to begin in 1993, he was assassinated in his apartment. Click here to watch the video clip Document Shows Vichy Leader Widened Anti-Jewish Law.

Jacob Bresler

Born in Poland, Jacob Bresler (b. 1928), was 11-years-old when he was deported, he survived five concentration camps. He lost his entire family in the Holocaust. Click here to read more about Jacob Bresler’s life.

Jacob had four sisters and an older brother, Josef. The day after the German Stukas bombed his city (1 September 1939), the family fled on foot. Returning a few days later, Jacob and his mother found their apartment and business had been ransacked with nothing left. The family eventually returned permanently to the city. In January 1940, Jacob’s father was relocated to a labor camp and two months later, the family was herded into a Jewish ghetto. Two years later, Jacob’s older sisters, Hinda and Golda, were deported and died in the gas chamber at KZ Chelmno, an extermination camp in northern Poland.

The Jews in the ghetto were relocated to the “Jewish Colony,” a group of six Polish villages appropriated by the Nazis. By mid-1942, Jacob and what remained of his family were marched to the Warsaw Ghetto. Jacob and his brother got separated from the rest when they joined a work detail. The two of them were eventually sent to the Łódź Ghetto where they lived together. In March 1943, Jacob met a transport from Poznań where his father had been interned. Remarkably, his father was on the train and they were reunited. Unfortunately, two weeks later, Jacob’s father was deported, and it was the last time they would see one another.

Jacob and Josef were put on the second convoy to leave the ghetto for Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Surviving the selection process, the brothers were shipped off two weeks later to Kaufering VII, a subcamp of KZ Dachau. Their next camp was Kaufering IV where they worked building the factory to build Messerschmitt jet fighters. Their job was to carry 100-pound bags of cement up a ramp twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Jacob was going to die, and he knew it. So, he hid. Three months later, Josef was transferred to Kaufering⏤it was the last time the brothers saw one another. Jacob was subsequently sent to Kaufering III, Kaufering XI, Landshut (another subcamp of Dachau), and finally, KZ Mühldorf. At the end of April 1945, Mühldorf was evacuated, and the prisoners were loaded into cattle cars. The train stopped in Tutzing (south of Munich) and Jacob was liberated by the Americans.

By this time, he weighed sixty pounds and was hospitalized with typhoid fever. In September, Jacob was moved to Landsberg am Lech, a displaced persons (DP) camp. He spent two years in the DP camp until one day in 1947, he saw a note on the communications board with a message. Someone by the name of Samuels was looking for him. Mr. and Mrs. Samuels lived in New York and they had been friends with Jacob’s parents. They had seen his name on a list of survivors and agreed to sponsor him to join them in America. That process took another two years, but Jacob finally made it to New York and the Samuels took him in with open arms. He was lucky. Many of the young survivors did not find their relatives or sponsors to be as accommodating or loving as Jacob experienced.

Jacob became Jack Bresler and joined the American army. Afterward, Jack moved to Vienna to study opera and film, worked as a television producer, owned restaurants, and other businesses. Jack married Edith sixty-one years ago and they have a daughter and grandchildren. He has returned to his hometown in Poland on two separate occasions.

Jack believes “People are repeating history. They haven’t learned a thing.”

But You Did Not Come Back

They spent one night too many in the Bollène château. After their arrest by the French police in 1943, fifteen-year-old Marceline and her father, Shloïme Rozenberg, were sent to the Drancy internment camp to await their convoy. Everyone knew where the trains were headed, and it wasn’t for “resettlement” or “labor in the East,” as the Nazis tried to deceive them. Shloïme told his daughter, “You might come back, because you’re young, but I will not come back.” Marceline went to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, while Shloïme ended up at Auschwitz I⏤the two camps were separated by 1.9 miles. One day, a Kapo (a privileged prisoner-work-squad leader) brought Marceline a written note from her father. Decades later, all she could remember was the salutation, “My darling little girl,” and the signature, “Shloïme”⏤not “Papa.” The content of the note has been lost to time, but seventy-five years later, Marceline drew from her memories to write a book, But You Did Not Come Back. The book, written as a letter to her father in response to his note, describes her experiences in the camp and as a returning deportee. (Click here to read The Auschwitz Portraitist.)

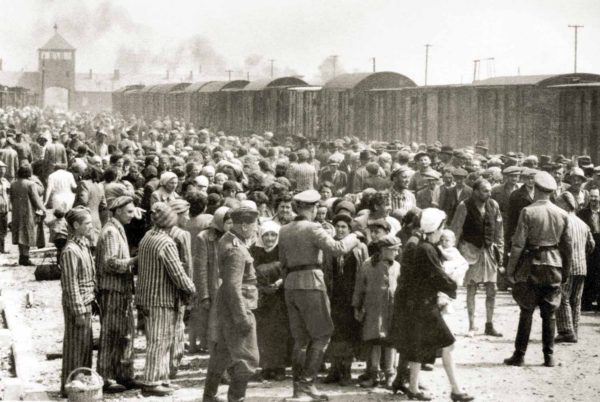

Marceline watched each day as the trains unloaded it human cargo. She saw the first groups of women, children, babies, and older people herded toward the gas chambers. They were stripped and marched into the chambers, where they were told a shower awaited them. Marceline’s work detail built the second railway line that led directly to the gas chamber. She was assigned to “Canada,” a term the inmates used to describe the sorting sheds filled with clothes from the Nazis’ victims. The best clothes were sent to Germany, while Marceline and the others wore the rags of the dead. New arrivals brought news of the war, and that is how Marceline learned that Gen. Leclerc’s tanks had liberated Paris in August 1944. When the Sonderkommandos (male prisoners forced to dispose of victims’ remains) revolted, Marceline and the others did not participate and were saved from certain death.

No one was waiting for Marceline when she arrived at the Hôtel Lutetia in Paris in April 1945. Her mother was living in Bollène. Mother and daughter were finally connected by phone and Marceline’s question whether her father had returned went unanswered. All she heard was, “Come home.” Marceline did not want to go home. She wanted to see her father, but she knew that he did not come back.

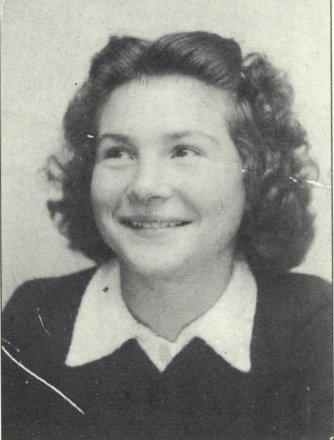

Sarah Lichtstein-Montard

Sarah Lichtstein (b. 1928) was born in Poland, but her parents moved to Paris and the three of them lived in a small apartment in the 20th arrondissement (district). Her father, Moise, had been deported in July 1941 and sent to the Pithiviers internment camp.

At six o’clock in the morning on 16 July 1942, a loud knocking on their apartment door woke up Sarah’s mother. Four policemen were there to arrest her. Sarah was not on the list. This was the infamous roundup of more than thirteen thousand Jews during 16/17 July. It is known as the rafle du Vél’ d’Hiv, or Vél’ d’Hiv Grand Roundup. Sarah followed her mother and boarded the bus that took them eventually to the Vélodrome d’Hiv on rue Nelaton. There, thousands of men, women, and children were left without water, toilets, food, or medical care. The detainees were told that they were to be sent to Germany for labor camps. As the people in wheelchairs began to appear, everyone quickly determined the officials were lying. (Click here to read the blog The Round-up and the Cycling Arena.)

Sarah managed to get out of the building and a half hour later, saw her mother on the same métro station platform waiting for the train. Her mother had slipped out of the Vélodrome by pretending to be a friend of a street-sweeper. Mother and daughter made it to the residence of friends where they hid for two years (documents reflect Sarah’s last address as 79, av. de la République). In May 1944, they were denounced and arrested.

After their arrest, they were taken to the Drancy internment camp. On 30 May 1944, Sarah and her mother boarded one of the cattle cars belonging to Convoy no. 75. Their destination was Auschwitz and there were 110 children onboard. Upon arrival at the extermination camp, it is incredible that both survived, and they were eventually transferred to KZ Bergen-Belsen where liberation came on 15 April 1945.

Very few of the deportees from the Vél d’Hiv roundup were alive when the war ended. Sarah and her mother survived. Sarah credits being saved by her mother and the French policeman who allowed her to escape the Vélodrome that July day. She is worried that history will repeat itself. Sarah says she does not allow hatred to guide her life. That would be very easy to do as you can imagine the horrors she saw at these camps. Sarah has chosen love and humor to propel her through life. She embodies the philosophy of “Forgive but never forget.”

The Surviving Children

Serge Klarsfeld estimates about 300 children survived out of the 11,146 children deported from France. Surviving children between the ages of twelve to fifteen accounted for less than fifty. None of the children under the age of twelve survived.

Public appeals for photographs of the children began in 1993. These appeals were broadcast on Jewish radio programs and published in Jewish press. France, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Israel, Austria, and the United States were blanketed with requests for the images. Today, the images of 2,502 children, or 22% of the deported children have been preserved.

★ ★ ★ Learn More About the Children Who Survived ★ ★ ★

Bresler, Jacob. You Shall Not Be Called Jacob Anymore. Scotts Valley,CA: CreateSpace, 1988.

Klarsfeld, Serge. Translated by Glorianne Depondt and Howard M. Epstein. French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Klarsfeld, Beate and Serge. Hunting the Truth: Memoirs of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld. Translated by Sam Taylor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Loridan-Ivens, Marceline. Translated by Sandra Smith. But You Did Not Come Back: A Memoir. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015.

Mr. Klarsfeld’s book serves as the primary source for today’s blog including some of the images.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We are entering the “slow season” as the snowbirds return north. The days are getting hotter. The tides are becoming more dramatic (we live on the water). And best of all, we can get into the restaurants without a wait (yes, Florida restaurants are wide open and have been for some time).

Sandy and I have decided to venture out in July by going to Montana for a week. All of the kids and grandkids will be there. We’re going to a small-town north of Flathead Lake. I tried four hotels before I was finally able to get the last room in the hotel: pandemic, what pandemic? If you are thinking of traveling in the near future, here’s some advice⏤book now! The pent-up demand is tremendous. We are actually booking trips into 2023.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Steve B. for his recent e-mail concerning our blog, “Paris Art Nouveau” (click here to read). Steve commented that he enjoyed the photos. Well, it was a topic that just begged for beautiful images. There are hundreds of images I would have liked to use but because of space considerations, it wasn’t possible.

For our long-time subscribers, you probably have noticed we use many more images in our blogs than we did years ago. One of the reasons is that Sandy posts most of them to Pinterest. We seem to get a lot of activity on our Pinterest sites, and this may account for the surge in subscriptions we’ve seen in the last several years. Anyway, if you want to experience Pinterest but can’t seem to find your way to our pages, please don’t hesitate to contact us. Sandy will be happy to walk you through the process. Here is the access portal:

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross