He once told his son, “To be a leader or commander, you must have some ‘son of a bitch’ in you.” Well, Gen. Lucius Clay was certainly not short of that trait. Nicknamed “The Great Uncompromiser” or “The Kaiser,” Clay’s reputation was built on his ability to manage large construction projects and solve complicated logistic problems. Gen. Clay had his fingerprints on some of modern history’s iconic (and dangerous) military and political events.

It’s interesting how a blog evolves. I decided to write about Gen. Clay and his role in solving supply chain problems immediately after D-Day and that would be it. However, as I researched the general, I found he was involved in so many other important events that my original content kind of took a back seat to his other accomplishments.

REVOLUTIONARY PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

These books are about Paris. They are about the places, buildings, sites, people, and streets that were important parts of the French Revolution. You are about to enter a journey into history beginning in 1789 at the village of Versailles with the procession of the Estates-General and ending on the Place de la Révolution with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794. This is your personal walking tour of the French Revolution as it occurred in Paris and Versailles.

Did You Know?

Did you know there is some really neat information out there that you can use at your next cocktail party to wow your friends?

Nine out of every ten living things live in the ocean.

Peanut oil is used for cooking in submarines. It doesn’t smoke unless heated > 450oF.

In ancient times, strangers shook hands to show they were unarmed.

Everything weighs one percent less at the equator. (Been to the Equator and felt so much better.)

Intelligent people have more zinc and copper in their hair. (That explains my deficient blood tests.)

The Earth gets 100 tons heavier each day due to falling space dust.

The Moon moves two inches away from the earth each year.

Gold is the only metal that doesn’t rust.

When a person dies, hearing is the last sense to go. (I wonder how they figured that out?)

Your tongue is the only muscle in the body that is attached at only one end.

The tooth is the only part of the human body that cannot heal itself.

Zero is the only number that cannot be represented by Roman numerals.

Thanks to Martin B. for sharing with us. He is clearly the most interesting person at a cocktail party.

Let’s Meet Lucius Clay

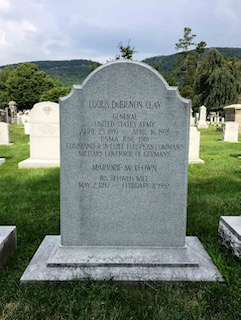

Lucius D. Clay (1898−1978) was the son of former U.S. Senator Alexander S. Clay (1853−1910) and Sara Frances White Clay (1861−1940) and the youngest of their six boys. He married Marjorie McKeown (1897−1992) and they had two sons: Lucius D. Clay, Jr. (1919−1994) and Frank Clay (1921−2006).

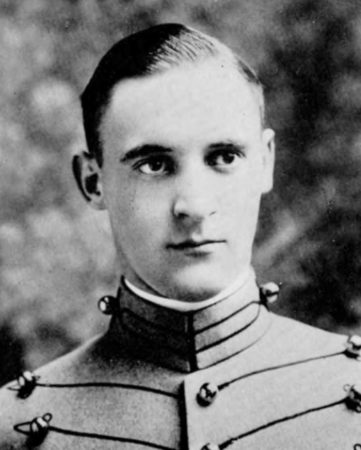

Clay graduated from West Point Academy in 1918 (both of his sons graduated from West Point in 1942) and he later taught at the academy. Following graduation and during the interwar period, Clay was part of the elite Army Corps of Engineers responsible for managing construction projects ranging from dams (e.g., Red River Dam) to civilian airports. (In 1940, President Roosevelt named Clay to run a program that eventually built 450 airports.) By 1942, Clay became the youngest brigadier general in the army when the president appointed him to run the military’s procurement program.

Gen. Clay developed a strong reputation for his administrative efforts to bring order and efficiency to complex and often, chaotic situations. He was known as a disciplined and driven task master who demanded perfection from his subordinates. One of his officers once said, “Gen. Clay is a great guy to sit down with after work and have a drink. Unfortunately, he’s always working.”

Although Gen. Clay never saw battlefield action during World War II (each of his sons distinguished themselves in combat during the war), he was crucial to unraveling the logistical material supply mess arising from the successful Normandy invasion on 6 June 1944.

The March to Germany

Gen. Clay’s responsibilities as the head of military procurement encompassed negotiating contracts, developing production schedules, disposing of surplus material, and most of all, making sure the troops in the field were properly supplied with food, weapons, and ammunition. Most of his war years were spent in Washington, D.C. where he developed close working relationships with key government individuals including the president’s trusted advisor, Harry Hopkins, and the House Speaker Sam Rayburn. Being close to the army chief of staff, George C. Marshall, didn’t hurt either.

The Army Service Forces, originally named “The Services of Supply,” was formed in February 1942 for the purpose of supplying the United States armed forces during World War II. It was organized along decentralized branches in each war theater including the European Theater of Operations. As part of the Normandy invasion planning, a detailed supply/shipping plan was approved. However, days after the invasion, the plan fell apart (there were dozens of reasons). An improvised strategy was implemented but the original timetable for Operation Overlord and the subsequent breakout quickly fell behind schedule.

Supply chains were in disarray shortly after D-Day. By September it became a critical problem and Gen. Eisenhower brought Clay to France to fix the problem. At the time, Cherbourg, France, was the designated entry point for Allied supplies but it took longer than anticipated to be taken by the Allied armies. Once liberated, the port became a bottleneck with supplies and material tangled up. In one day, Gen. Clay doubled the movement of supplies and within three weeks of arriving, materials were being unloaded and flowing without any blockage toward the front lines. (The decision was made to create the Mulberry Harbor as an alternate to Cherbourg; click here to read the blog, Mulberry Harbor & the Delta Works.) Gen. Clay was awarded the Bronze Star specifically for his leadership in Cherbourg and later received the Distinguished Service Medal for his work as Director of Material.

Postwar Germany

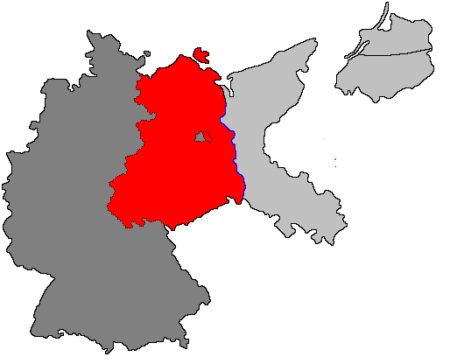

In July 1945, the Americans entered Berlin and established their occupation sector headquarters at the former Luftwaffe district offices on Kronprinzenallee in Berlin-Zehlendorf. As part of the 1945 (July 17 to August 2) Potsdam conference, the Allies (without French representation) agreed to a demilitarized and disarmed Germany. The country was to be divided into four zones of occupation (American, British, French, and Soviet Union). At the same time, it was agreed to divide Berlin into four sectors, but the city was isolated as it was located entirely within the Soviet Union sector of Germany (later known as East Germany).

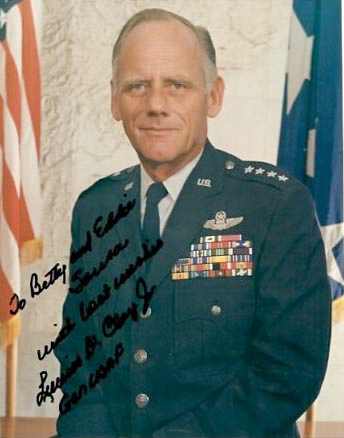

Almost immediately after the war ended, Gen. Eisenhower assigned Clay to be his deputy in charge of all civil affairs in Germany. Two years later, Gen. Clay became military governor of the U.S. zone of occupation and commander of all United States armed forces in Europe with a promotion to full general. Under his watch, the country became divided into West and East Germany.

Clay supported American efforts to move away from a policy of economic dismantlement (similar to the onerous World War I policies under the Versailles Treaty) to one that promoted economic reconstruction. (The general’s report, A Report on Germany served as a foundation for the Marshall Plan.) Gen. Clay believed it was his responsibility to “run Germany, not ruin it.” His approach was a humanitarian one but with a firm hand. He told the German people to stop feeling sorry for themselves, cease their grumbling, and get back to work. One of his first steps was to increase the flow of food into the country without fear of exploitation.

Probably one of the most controversial issues from his administration was the lenient treatment of convicted former Nazi war criminals. Despite his disappointment with the denazification efforts, Gen. Clay commuted death sentences that should have been carried out as well as reducing life sentences (some of these people were tried years later by West German courts). However, by 1948, Clay began to accelerate the pace of executions and after he was replaced in May 1949, his successor, John McCloy (click here to read the blog, The Wise Men) halted these executions and began to commute court mandated sentences.

The 1948 Berlin Blockade and Airlift

If Gen. Clay had retired immediately after the end of World War II, his place in history would have been assured. However, his greatest contribution to freedom was to come in mid-1948 and it ensured his name would be associated with the greatest airlift the world has seen.

The first major international crisis of the Cold War occurred on 24 June 1948 when the Soviet Union blocked access to West Berlin. All railways, roads, and canals leading across the Soviet sector to West Berlin were rendered unusable. Stalin ordered the blockade in response to new Allied economic policies including the introduction of a new currency, the Deutsche Mark.

Fundamentally, Stalin underestimated the resolve of the Americans and the British. He believed they would withdraw from their occupation zones within two years allowing the Soviets to unite Germany under Communist rule. In 1946, Gen. Clay stopped sending Stalin shipments of equipment from dismantled industries in response to the Soviet leader’s cessation of agricultural products to the west. For the next two years, the Allies frequently skirmished with the Soviets. One of the major issues was the unification of Germany and another was Berlin. (“What happens to Berlin happens to Germany and what happens to Germany, happens to Europe” ⏤ Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov.)

Land-based access rights to an isolated Berlin had never been formalized by the wartime Allied governments. However, the Soviets formally authorized three air corridors originating in the west leading to Berlin: Hamburg, Bückeburg, and Frankfurt. By March 1948 it had become clear that any working relationship between the four-powers had broken down and could not be resuscitated. At the end of March, the Soviets began tightening up control and access to Berlin. Gen. Clay knew exactly what the outcome was going to be.

On 19 June, the Soviets halted all trains destined for Berlin. They blocked access to the city via the autobahn and any waterway access had to be approved by the Soviets. Two days later, American military supply trains headed into Berlin were stopped by Stalin. On the 24th, all connections to Berlin were cut off while the West instituted a counter-barricade. At that point, all food going into the city was stopped. Power was generated in and supplied by the Soviet sector and predictably, all electricity to West Berlin was cut off. West Berliners only had 36 days of food and 45 days of coal.

Despite an overwhelming Soviet superiority in military forces surrounding Berlin, Gen. Clay was adamant that it was imperative to remain in Berlin. He believed Stalin was bluffing and was not about to risk a nuclear war over the occupation status of Berlin. The general rightfully concluded it was a Soviet tactic to gain concessions in their negotiations with the west. It was decided to “fight back” with an air lift despite military “experts” saying it could not be accomplished. When asked about air lift ability, commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Gen. Curtis LeMay (1906−1990)) told Clay, “We can haul anything.”

Gen. Albert Wedemeyer (1896−1989) was consulted about the feasibility of an air lift (he had commanded the U.S. airlift over the Hump to China during World War II) and gave his full endorsement to the operation dubbed “Operation Vittles” (the British code word was “Operation Plainfare”).

On 25 June 1948, Gen. Clay gave the order to commence the airlift. Besides America and Britain, other participating countries included Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Canada refused to assist while the French only airlifted supplies intended for its Berlin military personnel. American aircraft used the Tempelhof airport while British planes landed at Gatow airport. At the peak of the airlift, an aircraft landed every 45-seconds at Tempelhof.

The following day, thirty-two C-47s took off for Berlin with 80 tons of cargo. The first British planes landed at Gatow two days later. American C-54s flew from Rhein-Main Air Base while the airbase at Wiesbaden was a hub for C-54s and C-47s. The British airbases were in Hamburg and Hanover. Other aircraft included Yorks, Dakotas, DC-7s, and Short Sunderland flying boats. Initially, the operation was not running at maximum efficiency, but Gen. Clay quickly fixed the problems.

The Soviets ended the blockade on 12 May 1949 but officially, the Berlin Airlift did not end until 30 September (the planes kept flying because of distrust toward Soviet intentions). A total of 2.4 million tons of cargo was flown into Berlin during the nine-month airlift operation. The cargo planes flew 278,228 flights representing a total of 92 million flight miles. In today’s currency, the cost was about six billion dollars.

The aftermath of the Berlin Airlift saw the creation of West Germany, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and solidified the Cold War demarcation between East and West. It also confirmed the importance of Berlin as an icon of democracy and a lynchpin in the fight against Communism. It also created the “Berlin Problem” that Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy would have to address with the Soviet Union.

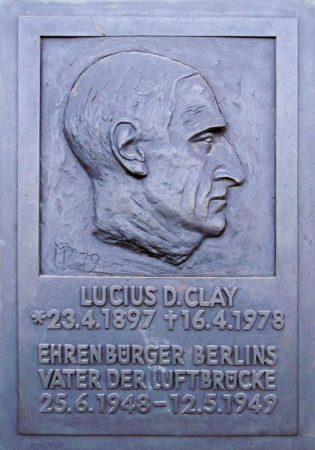

The citizens of Berlin never forgot that Gen. Clay was the man responsible for the airlift that saved them from potential Soviet domination. He became a German folk hero only three years after the defeat of Nazi Germany. As a measure of their gratitude and respect, the city of Berlin placed a memorial plaque at the base of Gen. Clay’s grave.

The U.S. Interstate Highway System

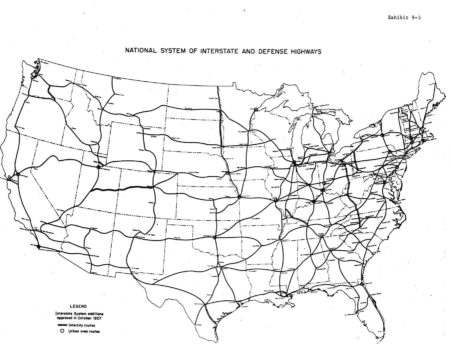

Gen. Clay was retired when President Eisenhower called upon his friend once more. The president had a vision of a sprawling transportation system in America, and he knew building a massive highway system would support the rapid movement of military equipment. On 29 June 1956, the president signed the Federal Aid Highway Act. Today our highway system is known as the “Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways,” or more commonly, the “Eisenhower Interstate Highway System.”

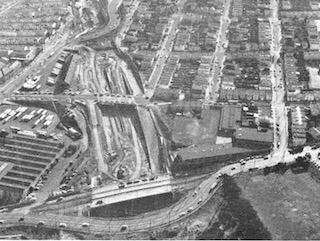

Eisenhower tasked his friend with the challenge of planning and building the federal system of highways. Gen. Clay’s background ensured this complex project would be finished and done correctly. He devised a 10-year plan to build about 40,000 miles of divided highways to link cities with populations of 50,000 or greater. The budget was $100 billion. A minimum of four lanes were required with no at-grade crossings (i.e., on and off ramps would be built).

Missouri was the first state to begin work on 13 August 1956. The interstate system was considered complete in October 1992 with the completion of I-70 in Colorado. Today, the highway system is 42,000 miles of concrete and asphalt. It ended up costing about $114 billion and took 35-years to complete.

The Berlin Problem

Stalin was dead and Nikita Khrushchev (1894−1971) was the Soviet leader when John F. Kennedy (1917−1963) took the oath of office of the President of the United States on 20 January 1961. Khruschev sent out subtle signals that he wanted to work with the new but inexperienced U.S. president. However, Kennedy and his advisors missed the signals and later mistook a run-of-the-mill speech given by Khruschev to be a sign that the Soviets wanted to escalate tensions between the two superpowers. Khruschev was convinced the new president was an “amateur” based on their discussions at the 1961 Vienna conference and Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs fiasco. This led to Khruschev’s belief that Kennedy and the United States would not oppose any aggressive moves by the Soviets in Germany or elsewhere. Gen. Clay knew better. His experiences convinced him that when the United States stood up to Soviet aggression, the enemy would back down.

The “Berlin Problem” was shared by both Cold War adversaries. The United States decided its policy toward Berlin would be to remain under all circumstances since leaving the city would damage its international reputation. The Soviets on the other hand had a bigger problem. East Germany and Berlin were losing massive amounts of their citizens to the west. If the migration (maybe a better word would be “escaping”) wasn’t stopped, East Germany would eventually cease to exist. Khruschev’s other problem was that if he didn’t take some sort of action, other Soviet satellite countries would likely follow suit and another Hungary type revolt would occur and need to be suppressed.

The common thread both leaders shared was the belief that Berlin was not worth risking a nuclear war. Conventional thought was the Soviets matched the United States in nuclear fire power. However, the truth was they were far inferior in the size of their nuclear arsenal. (I guess that matters under the “Mutual Assured Destruction” doctrine.)

The Berlin Wall

After serving President Eisenhower, Clay was once more called to duty by President Kennedy in September 1961. He served the president as his representative in West Berlin as a result of the East Germans blocking access to West Berlin. Returning as the “Hero of Berlin,” Clay’s mission was to reassure Berliners of the U.S. commitment to the city. Essentially operating independent of the state department and other chains of command, Clay began ordering military responses to the ever-growing threats of the East Germans and restricted access to the city. It was his opinion that the Soviets were calling the shots and not the East Germans.

Gen. Clay left Berlin in May 1962. Three quarters of a million West Berliners attended a farewell rally in his honor. There were no East Berlin citizens in attendance. The Berlin Wall had been erected nine months earlier to stem the tide of losing East Berliners to the west.

Gen. Clay passed away on 16 April 1978 from emphysema (he was a very heavy smoker). He is buried with his wife at West Point Academy. At the base of his grave is a stone tablet engraved with Wir Danken Dem Bewahrer Unserer Freiheit, or “We Thank the Defender of Our Freedom.” It was placed there by the citizens of Berlin who thirty years later had not forgotten the general’s efforts to keep the city free.

Gen. Lucius Clay left behind several legacies in two countries that today share a common theme: freedom to move about at will without government restrictions.

Next Blog: “The Red Tails”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bradley, Omar N. and Clay Blair. A General’s Life: An Autobiography by General of the Army. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974.

Clay, Lucius D. Decision in Germany: A Personal Report of the Four Crucial Years That Set the Course of Future World History. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1950.

Crosswell, D.K.R. Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith. Lexington: The University of Kentucky, 2010.

Dworak, David D. War of Supply: Word War II Allied Logistics in the Mediterranean. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2022.

Kempe, Frederick. Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2011.

Osmanski, F.A. Logistical Planning of Operation Overlord. Military Review. 29 (10): 50-62. ISSN 0026-4148.

Roll, David L. George Marshall: Defender of the Republic. New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019.

Smith, Jean Edward. Lucius D. Clay: An American Life. New York: Holt, 1990 (first edition).

Steil, Benn. The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

U.S. Army. Logistics in World War II: Final Report of the Army Service Forces. Washington, D.C.: U.S.G.P.O., 1948.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are looking forward to yet another cruise. This time, we’ll sail to the Caribbean with our son and his family. We took this cruise for two reasons. First, to celebrate our 45th wedding anniversary and second, we wanted to experience New Years Eve onboard. The last time Sandy and I went out on New Years Eve was probably about forty years ago. Crazies on the road, poor dining experiences, and diminishing expectations always led to early bedtimes on that evening (at least for me). Well, we’ll see how it goes on board a cruise ship where all we have to do is walk to our cabin after ringing in the new year.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

We heard back recently from our friend, John Winn Miller. If you recall, John was our guest blogger a year ago with Five Surprising Things I Learned Researching My World War II Novel. John had recently published his book, The Hunt for the Peggy C. Click here to read the blog.

John told me he has wrapped up an early draft of his third novel. He was excited to read about Johnny Nicholas in our blog, Find Johnny Nicholas!, because he was able to add a fictionalized version of Dr. Johnny to the novel. (Click here to read the blog.)

For those of you who read and enjoyed the first volume of John’s trilogy about Capt. Rogers and Miriam, please keep an eye out for the second volume that is projected to be published in October 2024.

Thanks, John, for keeping us updated and I’m glad we were able to contribute a “value added” idea for your story.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

One of the most interesting pieces of yours that I have read.

I knew about the Berlin airlift but nothing about its “mastermind”. and certainly nothing about his involvement in post D-Day logistics nor his role in the creation of the U.S. interstate Highway system.

Merci!

Hi Kim, Thanks for your comments. It was an interesting subject to research. I started by thinking all I was going to write about was Gen. Clay’s involvement in solving the supply jams after D-Day. The more I got into it, the more I realized he had his fingerprints on many of the iconic Cold War events as well as the interstate highway system. I’ll keep trying to come up with other interesting topics. STEW