The war against Hitler and Germany ended in early May 1945. Europe and in particular, Germany, was in ruins. Millions of people were displaced. Estimates of displaced persons (DP) ranged between forty to sixty million including homeless, concentration camp survivors, labor camp inmates, and liberated prisoners of war.

European infrastructures were destroyed, food supplies were disrupted to the point where people continued to go hungry, coal for heating was still scarce, major transportation corridors were rendered useless, and manufacturing facilities had been bombed to the point where they could no longer function. (German factories suffered the most both from bombs and equipment pilfering by the Soviets.)

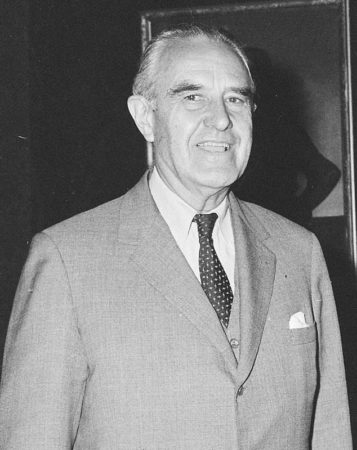

Gen. George C. Marshall (1880−1959), U.S. secretary of state, knew that it was imperative to get Europe back on its feet. The 900-lb gorilla in the room was the Versailles Treaty signed by Germany twenty-five years earlier. The terms of the treaty were so onerous that it was generally considered to be the catalyst for the emergence of Hitler and the Nazis. Gen. Marshall had a vision of the “new” Europe, and its prosperity would need to include all countries, including Germany.

The core of Gen. Marshall’s vision was comprehensive American economic assistance to the Europeans. There were two components for accomplishing this vision: creating a working plan and then the execution of the plan ⏤ in other words, getting it approved and funded by the American Congress. He acknowledged that the easy part was putting a plan together and the “heavy task” was “the execution” of the plan.

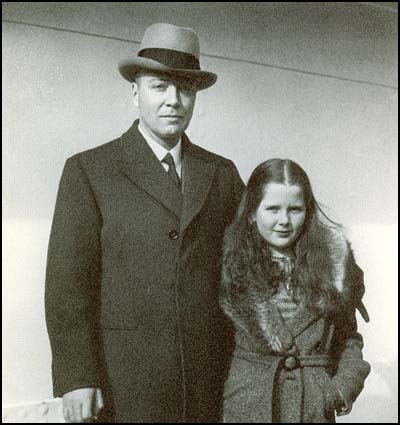

To begin the process of developing an economic aid plan, an eighteen-member council was assembled. It was chaired by Averell Harriman (1891−1986), President Truman’s secretary of commerce. The council consisted of business leaders (e.g., CEOs of General Electric, B.F. Goodrich, and Procter & Gamble), labor leaders (e.g., George Meany of the AFL), academics, and public officials. The mission of the council was to develop a report on the “limits with which” the U.S. could provide economic relief to the Europeans. The President’s Committee on Foreign Aid, or the “Harriman Committee” as it was known, provided the road map that eventually became the “European Recovery Program” (ERP) and the final bill, “The Foreign Assistance Act of 1948.”

Then and now, it is commonly referred to as the “Marshall Plan.” Read More The Harriman Committee