Historically, people have reacted in three primary ways to totalitarian and fascist regimes such as Hitler and his Nazi party: they support it, they oppose it but do nothing or, they oppose it and become a resistance fighter (in small or large ways).

We normally associate resistance to the Nazi regime as something that occurred in the occupied countries. As we saw in our last blog (Hitler’s Blood Judge, click here to read), there were organized resistance movements, albeit limited, within Germany (e.g., The White Rose Movement). Unfortunately, the Gestapo and other police units were able to effectively shut them down and turn the “traitors” over to the show-trials presided by judges such as Roland Freisler.

However, there were several well-known German resistance organizations which operated not only in Germany but in several of the occupied countries and one neutral country. As we’ll see, several of them were quite successful during the limited time they had. Because it was assumed the resistance groups reported to Moscow, the Gestapo gave them the collective name of Die Rote Kapelle or, The Red Orchestra.

Did You Know?

Another organization the Gestapo and the S.D. or, Sicherheitsdienst (the SS intelligence service) targeted was Die Swartz Kapelle or, The Black Orchestra. Led by General Ludwig Beck, the Black Orchestra was a loosely organized network of high-ranking German Wehrmacht and Abwehr officers. During the mid-1930s, they believed Hitler was rushing to war before Germany was adequately prepared. Their initial opposition was not based on replacing Hitler, rather trying to convince him to wait until the country was ready to wage a successful war.

However, by the late 1930s and in particular, after the Munich Agreement, the clandestine military opposition changed to a goal of overthrowing Hitler. During 1938 and 1939, numerous plans to assassinate Hitler were drawn up including the failed attempt to detonate a bomb on Hitler’s airplane. By spring 1940, Hitler’s successful strategies enhanced his reputation with the Germans and the conspirators began to dissipate because they felt the general public would not support a regime change.

However, by the summer of 1943, Operation Barbarossa (the invasion of the Soviet Union) had failed and Hitler didn’t look like the genius everyone thought he was only four years earlier. At that point, questions were beginning to be asked about Germany’s ability to win the overall war. The conspiracy to overthrow Hitler was revived albeit with less participation than before. By this time, the Gestapo and the S.D. had caught onto the discontent at the top of the military chain. One of the leaders of the Black Orchestra was Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr—the German intelligence organization which reported up through the high command of the Wehrmacht (as opposed to the competing intelligence agency, the S.D. which reported to Heinrich Himmler). Other members of the Black Orchestra or at least willing participants, included the German ambassador to Rome, the mayor of Leipzig, most of Canaris’s staff, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, General Ludwig Beck, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, General Carl-Heinrich von Stüpnagel (the German Military Governor of Paris), and other high-ranking officials. There were enough well-placed officers to support Colonel von Stauffenberg’s plot to kill Hitler on 20 July 1944.

Operation Valkyrie failed and the Gestapo had no trouble rounding up the Black Orchestra conspirators (and their families). Gestapo records indicated more than 7,000 people were executed as part of their role in the conspiracy. General Beck attempted suicide but only wounded himself—a soldier was sent into the room to finish off the job. The Black Orchestra ceased to exist at that point.

Die Rote Kapelle

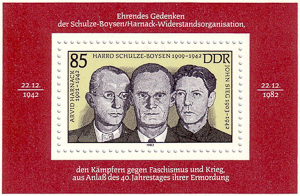

The Red Orchestra received its name because the Nazis considered these resistance groups to be run by Communists and the Soviet Union. Red Orchestra was an all-inclusive term used for three separate groups: the Lucy spy ring, the Trepper Group, and the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group. Members of these groups were predominately intellectuals who either were Communists or who leaned towards Communism. Resistance within Germany by the intellectual community was divided into three categories: “Inner Emigration” was the term given to the intellectuals who left the big cities and moved to a rural setting to wait out the war. The next step was Resistenzor, the daily act of resisting by noncompliance with certain expected behaviors. These might include refusing to give the Nazi salute or not contributing to fund-raising efforts for the war. The last and most dangerous act of overt resistance was called Widerstand or, “taking a stand against” the Nazi regime. The Red Orchestra was committed to Widerstand and each member knew the consequences if caught. Read More Die Rote Kapelle