A while ago, I wrote a blog about a French footballer who was a rather despicable human being (click here to read the blog, Les Bleus, Le Collabo et L’exécution). Today, we will discuss two other footballers, one was Norwegian while the other was German. During the interwar period, Asbjørn Halvorsen and Otto Fritz Harder played together for the same German football club in Hamburg.

As we will see, during World War II, these two men were on different teams and one of them would be subjected to the brutality brought on by the other.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the Napoléonic Code prohibited women from owning businesses in France without the permission of their father or husband? There was one exemption: widows. This created a loophole for three champagnes many of us enjoy today: Veuve Clicquot, Champagne Pommery, and Champagne Bollinger. (The French word for widow is Veuve.)

François Clicquot died in 1805 leaving his 27-year-old widow, Barbe-Nicole Clicquot-Ponsardin, with the responsibility of running the family’s small textile and wine business. Rather than selling the business and retiring to the salons, Barbe-Nicole asked her father-in-law for a rather substantial amount of money to expand the business. Remarkably, he agreed. Champagne had a rather dubious reputation at the time since it was the preferred drink at parties thrown by the royals and nobility. (You can imagine some of the outcomes.) So, Barbe-Nicole decided to add “Veuve” to the name of the champagne. Doing so gave the champagne a certain amount of dignity thus overcoming the debauchery image. She grew the business but, on several occasions, it almost reached the point of bankruptcy. One such instance occurred in 1814 during the Napoléonic Wars when many European borders, including Russia, were closed. Barbe-Nicole decided to run the Russian blockade because she knew if her champagne got into Russia before her arch-competitor, Jean-Remy Moët, Veuve Clicquot would become the dominant player in that space. It was a huge risk because of the weather and possible confiscation of the inventory. However, everything went as planned and within ninety-days, Barbe-Nicole’s champagne was king. She became known in Russia as the “Widow.” Barbe-Nicole went on to become an innovative winemaker and extremely successful.

In 1858, Louise Pommery’s husband died, and she took over Pommery et Greno, the champagne house her deceased husband co-founded two years earlier. While Barbe-Nicole conquered the Russian market, Louise set her sights on England. Champagne was very sweet with a high sugar content. Louise knew the English had a palette for a drier taste, so she modified the formula in 1874 to create a dry, fresh, and lively taste. It was a hit, and her brut champagne took over the English market.

Jacques Bollinger passed away in 1941 and his widow, Lily Bollinger, took over Bollinger Champagne. By the mid-1960s, Lily developed new techniques and a “new” champagne was born. Today, Bollinger is one of the most sought-after champagnes.

None of these pioneering women remarried. It is likely their choice was based on the fact they would lose their independence, legal status, and be required to turn the business over to their new husband. Gen. Charles de Gaulle gave French women the right to vote but it wasn’t until 1965 that they were granted full rights to employment, banking, and asset management.

Let’s Meet Asbjørn Halvorsen

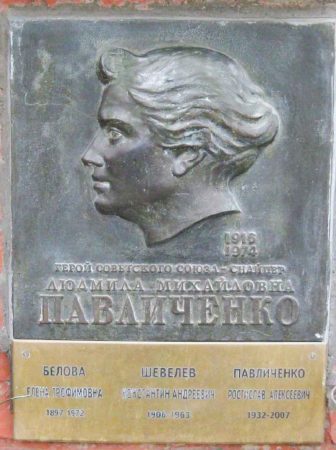

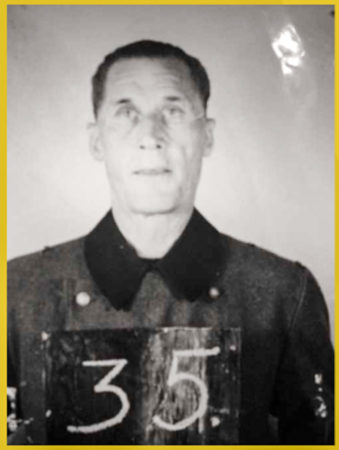

Asbjørn Halvorsen (1899−1955) was born in Sarpsborg, Norway. He eventually became a ship broker in Hamburg, Germany and married a German woman. However, Asbjørn is best remembered for his football career, both in Norway and Germany. What is forgotten (or not spoken about) are the years he spent in Nazi concentration camps.

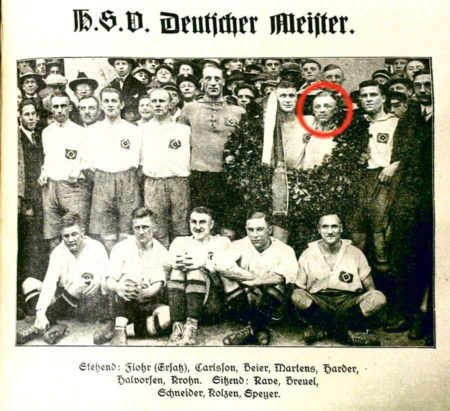

While living in Norway, the 18-year-old played center-half for Sarpsborg FK, a Norwegian professional football club. He starred at Sarpsborg FK for five years before moving to Germany and playing for Hamburg Sport-Verein, a German professional football club that won the German league in 1923 and 1928. Beginning in 1918, Asbjørn played for and captained the Norwegian national football team, accumulating nineteen caps (i.e., international appearances). His nineteenth and last international game for Norway was in 1923, coincidentally, against Germany in Hamburg.

Returning to Norway in 1933, Halvorsen worked for the Norwegian Football Association (NFF). This position required him to head up the national team’s selection committee (players and coaches) and in the years prior to World War II, Halvorsen was the coach of Norway’s national team. Under his leadership, Norway won the bronze medal at the 1936 Olympics (held in Berlin) and qualified for the 1938 World Cup (the last world tournament until 1950). It wouldn’t be until 1994 that Norway would qualify for another World Cup.

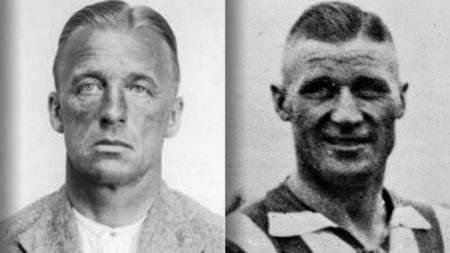

Let’s Meet Otto Fritz Harder

Otto Fritz (“Tull”) Harder (1892−1956) was born in Braunschweig, Germany. Like many other talented athletes, Otto was discovered early on for his football talents. He played for Eintracht Braunschweig, the main football club in the city, between 1909 and 1912. Although a very popular player with the fans, Otto did not get much playing time and in 1912, signed with the Hamburger Sport-Verein club and played there until 1931. Otto’s last professional football club was Victoria Hamburg where he retired in 1934. Otto accumulated fifteen caps playing for the German national team between 1914 and 1926.

Hamburger S.V. (HSV) was formed in 1887 and is the only team to play in the modern Bundesliga league since its inception in 1963. The club played in the top tier until the team was relegated to Bundesliga 2 after a disastrous 2017-2018 season. Ever since 1977 Hamburger S.V. has had a close affiliation with the Rangers, a top-tier Scottish football club. HSV’s fans visited Ranger games and modeled their new fan club on the Rangers’s fan club.

Interwar Period

Just before Halvorsen retired from HSV, a testimonial game was held to honor his time with the club. When the Nazi salute was ordered, Halvorsen was the only member of the team to keep his arm at his side. Three years later, Halvorsen and his national team were in Berlin’s Poststadion for the quarterfinals of the 1936 Olympics against Hitler’s German national team. As Hitler watched (and fumed), Norway beat the Germans 2 to 0 and days later, won their first and only international football award, the bronze medal. (Norway went on to lose to Italy, the eventual winner of the gold medal.)

On a September day in 1933, Halvorsen was standing on the rail platform at the Hamburg train station waiting to board his rail car for the journey back to Norway. Harder was rushing to the station to say goodbye to his former teammate. Halvorsen was a very creative footballer and responsible for many of Tull’s clinical finishes into the back of the net. Tull wanted very much to see his old friend off to thank him and wish him well for the next phase of his life. Germany was in the early stage of the Third Reich and neither man knew the horrors that awaited them and the world.

While Halvorsen continued his football career albeit in coaching and administration, Harder joined the Nazi party in 1932 and the following year, joined the Schutzstaffel (SS). Originally formed as Hitler’s bodyguard unit, the SS became one of the Nazis’ instruments of terror along with the Gestapo and Sicherheitsdienst. The SS was responsible for running the concentration and extermination camps, the Einsatzgruppen mobile death squads, and the wholescale massacres of civilians. After the war, the SS was declared a criminal organization and its members, including Otto Harder, were automatically deemed to be criminals due to the crimes against humanity they committed.

World War II and Occupation

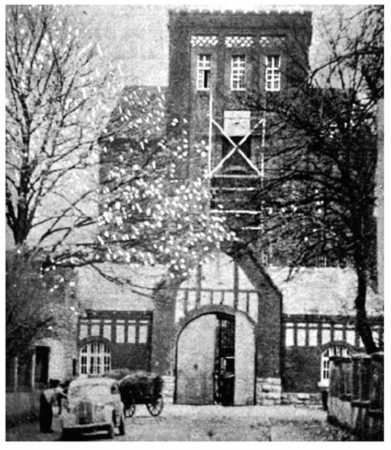

Harder’s first assignment in the SS was guarding inmates at KZ Sachsenhausen, north of Berlin. In 1939, he was transferred to KZ Neuengamme where he worked in the main camp as an administrator.

On 8/9 April 1940, the German army invaded Norway. The Norwegian royal family fled to London to form a government-in-exile. The German occupying forces were commanded by Gen. Nikolaus von Falkenhorst (1885−1968) and quickly demanded that the Football Association capitulate to German control. Halvorsen wrote a letter of protest to German high command and later that year, he tried to prevent Nazi flags from being flown at the Norwegian Cup final. Under Halvorsen’s leadership, sports organizations went underground and became important resistance groups. Their activities included boycotts and sabotage. Unfortunately, Halvorsen’s activities eventually caught up to him.

KZ Neuengamme

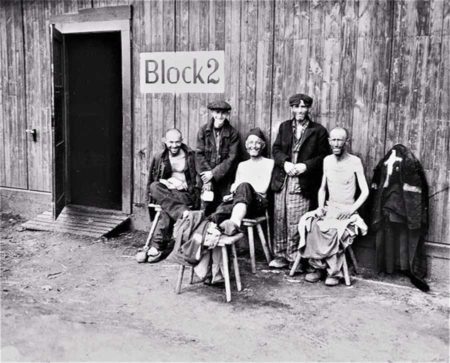

In August 1942, a small basement in an Oslo building was raided and searched by the Germans. They found a printing press used to publish resistance newspapers. It was a resistance operation supported by Halvorsen and he was immediately arrested. For one year, the former footballer was imprisoned in Bærum, Norway at the Grini detention camp, but he knew eventual deportation to Germany would be his fate.

His premonition was correct. Deported under Hitler’s directive, Nacht und Nebel, Halvorsen arrived at KZ Natzweiler-Struthof in France (click here to read the blog, Night and Fog). As a prisoner under the Nacht und Nebel directive (NN), Halvorsen was to be killed without any leaving any trace of his existence. Natzweiler was one of the primary destinations for NN prisoners and it was a camp where inmates were expected to die from abuse and overwork in the quarry. Only about 266 of the 504 Norwegian prisoners at Natzweiler survived and Halvorsen was one of them. As a former footballer on a German club team, many of the guards remembered Halvorsen and extended special treatment (which he shared with other inmates).

In August 1944, Otto Harder was promoted to SS-Untersturmführer (i.e., second lieutenant) and given command of KZ Hannover-Stöcken (Continental), a subcamp of KZ Neuengamme. This subcamp was established for the purpose of providing forced labor to Continental-Grummiwer AG, a rubber factory located in Stöken. Harder commanded sixty SS men at the camp and he was directly responsible for the inhumane living conditions and brutal treatment of the prisoners including executions. It is believed that about four hundred prisoners died at the Stöcken subcamp. On 30 November 1944, Harder was ordered to evacuate the camp and move everything to KZ Hannover-Ahlem, another Neuengamme subcamp located about three miles from Stöken. This time, the camp’s inmates were supplied to the local sugar factory as forced labor.

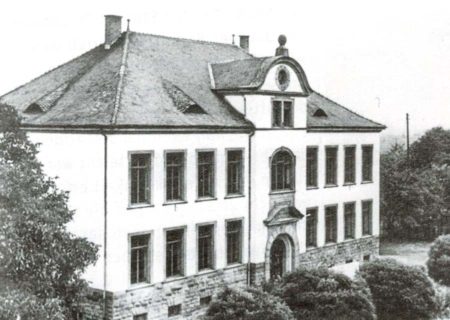

In September 1944, Halvorsen was relocated to KZ Neckarelz I, a subcamp of Natzweiler. The prisoners were housed in a former school building and forced to work in the nearby gypsum mines for the Daimler-Benz company. The following April, Halvorsen was transferred once again. He arrived at Neuengamme on the outskirts of Hamburg but his old teammate, Otto Harder, had left his position only a few months earlier. By this time, Halvorsen was very sick and fighting famine, epidemic typhus, pneumonia, and other illnesses. The evacuation of Neuengamme’s subcamps began in March 1945 with prisoners forced to march to other concentration camps. The main camp was evacuated on 2 May 1945 and the next day, British troops arrived at the camp. Despite the SS trying to destroy incriminating evidence, the documented death toll at Neuengamme was more than forty-two thousand in addition to the thousands of atrocities (including medical experiments on children) committed at the camp by the Nazis.

Postwar

Harder was arrested by the Allies and became one of the defendants in the Curio-Haus Trial between 16 April and 6 May 1947. As the former commander of KZ Hannover-Ahlem, Harder was charged by the British military tribunal in Hamburg with crimes against humanity. He was found guilty and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Harder only served four years in Werl prison before being released. He died about five years later. It is unlikely that Harder and Halvorsen ever saw one another again after their farewell meeting on the rail station platform in 1933.

Halvorsen was rescued by the Red Cross in April 1945. The Norwegian patriot was so weak that he could not be transported by the buses. Halvorsen did survive and made his way to Oslo in late May where he continued his recuperation. A year after his release, he was interviewed and said, “Starving is the cruelest thing. The sucking in the stomach is nearly unbearable and we did the most incredible things to numb the ache.”

Asbjørn Halvorsen returned as the Norwegian Football Association’s general secretary and is credited with setting up a new league system. Halvorsen traveled with the national team to Hamburg where they were to play the German team in a qualifying match for the 1954 World Cup. By then, most of the former Nazis convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity had been released from prison.

Halvorsen died in June 1955 suffering from the aftereffects of his time in the Nazi camps. Torture, maltreatment, and typhus likely caught up to him at the young age of fifty-six. Otto Harder was one of the enablers of the process that contributed to his former friend and teammate’s death.

“We shouldn’t mix up forgiving or forgetting.”

⏤ Jurgen Kowalewski

Retired history teacher

Next Blog: “The Marvelous Madame Hamelin”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Article:

Radziemski, Lily. The Little-Known History of Champagne. BBC World’s Table, 2 March 2023.

Article:

Lara, Miguel Ángel and adapted by Billy Munday. Spain visit the home of Asbjorn Halvorsen, the man behind Norway’s greatest football achievement. Marca, 10 December 2019.

Article:

Ulrich, Ron. Asbjorn Halvorsen and Otto Harder – the story of two team-mates and a war. BBC Sport, 3 March 2023.

Megargee, Geoffrey P. (Editor). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933−1945. Volume 1, Part B. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (Published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), 2009.

Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Elfde Gebod. Torfburg 10, Antwerpen. +32 (0) 3 288 5733 (Opens at noon). Click here to visit the web-site.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I recently returned from a wonderful week sailing the canals and rivers in the Netherlands and Belgium. We visited Keukenhof (the famous tulip park), the museum dedicated to the 1953 flood and subsequent Delta Works, and beautiful towns such as Hoorn, Antwerp, and Bruges. While in Antwerp, we came across an excellent restaurant located next to the cathedral. It’s easy to miss but Elfde Gebod is well worth skipping your ship’s lunch. The atmosphere is eclectic (the building dates to early 15th-century), the service is awesome and best of all, the food is superb. Both Sandy and I had the asparagus soup to start followed by mussels and Belgian fries (don’t call them French fries). Like many other Belgian restaurants, the choices of beers were staggering. Get there early because it is very popular with the locals. I have listed their contact information in the recommended reading section.

More on our trip in subsequent blogs.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Anne-Marie E. for contacting us regarding our blog, The Marcel Network (click here to read the blog). Anne-Marie’s husband was one of the children saved by Odette and Moussa Abadi from certain death. It is always interesting to hear from the families of the people I write about. Their personal stories always add an additional dimension.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross