So you read the title of this blog and automatically assumed I was going to share my opinion with you concerning recent events around our country. You were interested to know what I thought about the desire and the movements to destroy or relocate certain statues, paintings, or other memorials that certain people might find offensive.

No, I wanted to talk with you today about the deliberate destruction of approximately 1,750 bronze statues throughout France during the German Occupation of World War II. Not since the French Revolution had so many statues been destroyed (albeit for different reasons).

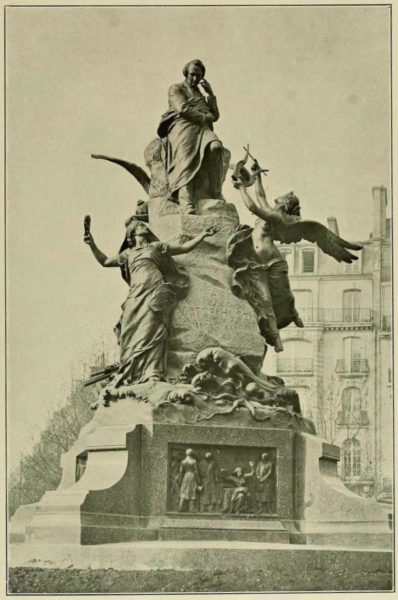

During the latter part of the 19th-century, the French government known as The Third Republic began a wide-spread campaign to erect bronze statues. These men (Joan of Arc being the lone woman) were considered heroes of France but in the minds of the citizens, they were closely associated with a widely considered corrupt government. This period of time was sarcastically dubbed “Statuemania.” Learn more.

What Happened?

Well, first of all, the Nazis invaded France on 14 June 1940 and began a four-year occupation. Hitler created two zones in France: The Occupied and Unoccupied (Paris was in the Occupied Zone). After seventy years in existence, The Third Republic was replaced by the Vichy government headed by Marshal Pétain and Pierre Laval.

Pétain’s collaborationist government was located in the small spa town of Vichy—the Unoccupied Zone. By November 1942 with the Allied successes in North Africa, all pretenses of a separate government were gone when the Germans eliminated the Unoccupied Zone and began to increase their direct role in running occupied France including higher demands for agricultural products and other resources (including non-ferrous metals) to feed the Nazi military machine. Learn more about the Vichy government here.

After France was liberated in August 1944, it became clear that Pétain and Laval had sanctioned laws, decrees, and actions that far exceeded Nazi expectations (including quotas for the deportation of Jews). During their separate trials, Pétain and Laval tried to argue in their defense that they were only trying to keep the Nazis happy and so avoid greater hardships for the French—at least as long as you weren’t a Jew, Freemason, communist, gypsy, homosexual, political opponent or any other type of untermensch (inferior person). Read More Statuemania