Everyone who travels returns home with certain images imbedded in their memories. One of the images of Paris that I have always retained is the decorative entrances to the métro stations. No, not every bulky, uninspired, or “run-of-the-mill” station but rather, those métro entrances that exhibit the iconic flamboyant signage designed in the style of Art Nouveau.

What is “Art Nouveau?” Art Nouveau, or “New Art” was an art movement that began around 1890 and ended in 1910. The movement was international (in England, it was known as “Modern Style”) and exhibited a style inspired by flowers and plants. There is a lot of movement with asymmetrical but sinuous and elegant lines. Materials used included glass, iron, and ceramics. By the end of World War I, Art Nouveau had disappeared and was replaced by Art Deco followed by Modernism.

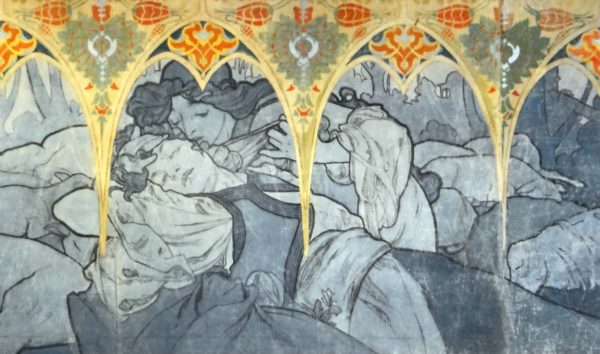

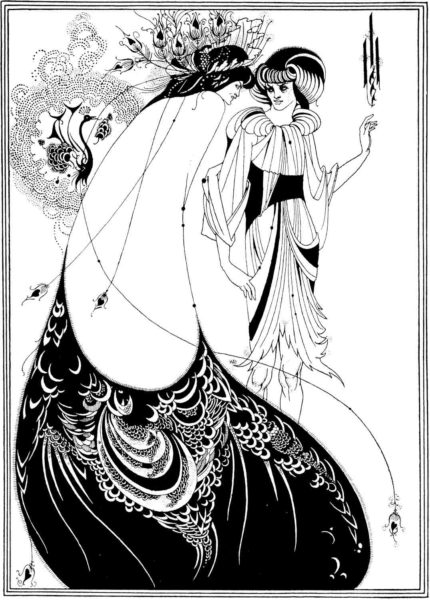

Art Nouveau was influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement (originating in Great Britain) and the first Art Nouveau architecture and interior design appeared in Brussels in 1890. It was quickly adopted by Hector Guimard in Paris. Artists such as Guimard, Alphonse Mucha, Aubrey Beardsley, and Louis Comfort Tiffany were leading proponents of Art Nouveau in architecture, jewelry, posters, graphic arts, and furniture. Mucha rejected the terminology of Art Nouveau. He said, “Art is eternal, it cannot be new.” However, the Paris art world quickly termed Art Nouveau as “le style Mucha,” or Mucha Style.

Guimard was the first to embrace Art Nouveau in Paris when he agreed to design the first generation of entrances to underground stations of the new Paris métro system at the turn of the century. Read More Paris Art Nouveau