The origins of slang names used for various combatants or combatant nations are acknowledged to be somewhat diffuse and shrouded by time. Today, many of the ethnic nicknames used during World War II are, rightfully, considered disparaging. The slang term for common British soldiers, “Tommy,” reportedly referred to a dying soldier named Private Thomas Atkins whose last words to the Duke of Wellington were, “It’s all right sir, all in a day’s work.” Slang names for Germans were numerous but one used during World War II was “Fritz.” This was the German pet form of Friedrich (the French used the slur, “Boche,” or hardhead). Germans and others used “Ivan” as the generic term for the Soviet foot and rifle soldier. It was a popular male name in Russia, especially for the ruling class (e.g., Ivan the Terrible).

Whether one was a Tommy, Fritz, or Ivan, the life of an ordinary soldier during war is a tough one. However, not all warrior lifestyles are the same. During World War II, of all the major combatant armies, I would say the Soviet soldier undoubtedly suffered through the hardest five years.

Did You Know?

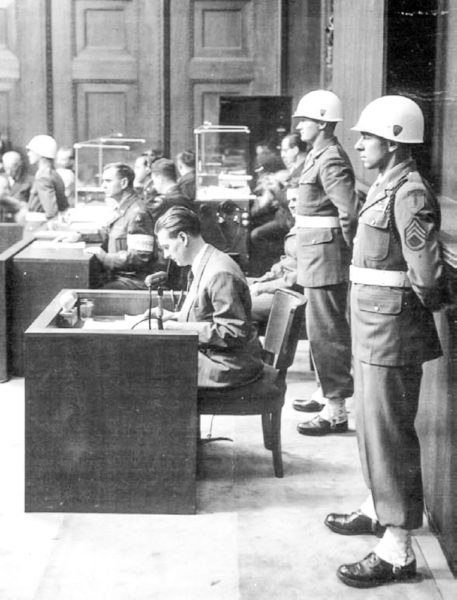

Did you know that at eighteen, Emilio “Leo” DiPalma (1926-2020) was drafted into the United States Army in 1944 and joined the 79th Infantry Division? At the age of nineteen, Staff Sgt. DiPalma was guarding twenty-one Nazi war criminals on trial in Nuremberg (three defendants were not present). Seventy-five years ago, he found himself standing in Courtroom 600 where on 20 November 1945, the International Military Tribunal (i.e., the main Nuremberg Trial) began with the reading of the indictment by representatives of the American, British, French, and Soviet prosecution teams. The trial lasted 218 days and culminated with verdicts of guilty for all but three of the defendants.

Sgt. DiPalma’s first assignment upon arrival was to make copies of documents. Then Sgt. DiPalma was assigned to guard the prisoners in their cells. Soon, he was transferred to the courtroom as a guard. Standing next to the witness box, Sgt. DiPalma was a witness to the evidence of Nazi atrocities. Mr. DiPalma later recalled how he was shocked at the evidence presented to support one of the four indictments ⏤ crimes against humanity. When court was in recess, Hermann Göring frequently asked Sgt. DiPalma for a glass of water. After drinking the water, Göring would complain and say, “Bah, Americanish,” and hand it back. One day, Sgt. DiPalma had had enough of Göring’s complaining and filled the glass with toilet water. After drinking the water, Göring’s response was, “Ahhh, gute vasser!”

Mr. DiPalma always said that was one of his war contributions.

More than seventy veterans at the Holyoke Soldiers Home in Massachusetts contracted and died from COVID-19. Unfortunately, Mr. DiPalma was one of those veterans.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

On 23 August 1939 in Moscow, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. Essentially, it was a peace treaty between the two countries and divided up Poland. Within a week of its signing, Hitler invaded Poland and World War II officially started. Two weeks later, Joseph Stalin ordered his army to invade Poland. The country was cut in half; the western half occupied by Germany and the eastern half by the Soviets. The truce lasted less than two years.

Operation Barbarossa

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact ended on 22 June 1941 when Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union. Despite warnings, Stalin was caught off-guard. Stalin’s “Great Purge” was on its last legs by June 1941. His officer corps was decimated, and for the most part, their replacements lacked military experience. They were young and their appointments were politically motivated. Unfortunately, it would be the common foot soldier who took the brunt of their leaders’ inexperience.

The Great Patriotic War

There were two distinct periods for the Soviet army: before the Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943) and after the battle. Prior to Stalingrad (today the city is called Volgograd), the army was unprofessional, lacked leadership, supplies were scarce, and morale was terrible (just to name a few of the issues). However, after winning the battle, the spirit of the soldiers and military leaders increased dramatically. Of course, the Communist Party took the credit. One German said, “The Russians are not men, but some kind of cast-iron creatures.” A Luftwaffe pilot wrote home, “I cannot understand how men can survive such a hell. Yet the Russians sit tight in the ruins, and holes and cellars, and a chaos of steel skeletons which used to be factories.” The German 6th Army was destroyed. German casualties totaled more than 282,000 while the Russians sustained more than 1.1 million casualties during five months of fighting. After the battle, the tide of war changed in favor of the Soviet Union and the westward march toward Berlin began.

Somewhere between forty and fifty million people were killed during World War II. Approximately twenty to twenty-seven million were Russians (compared to less than 250,000 for each of the United States and Great Britain). Within six months of Hitler invading the Soviet Union, 4.5 million Russians were dead, and 2.5 million soldiers were captured by the Germans. By the winter of 1941, one third of Soviet territory was occupied by the Germans and by 1943, eleven million Russian men and women fighting on the Eastern front had been killed. The Red army went through two separate generations of soldiers during the war ⏤ the average frontline tour of duty was three weeks. Even as late as the end of 1942, if someone was still alive after six months in the field, they were considered to be a hardened veteran. Things looked very dim for the Soviets ⏤ at least until February 1943.

The Soviet Soldier

The Soviet soldier has always been admired by others for their fighting ability. They exhibited patience in regard to thirst, hunger, and cold ⏤ three quarters of the army were peasants and they were used to the hard life. Soldiers were always ready to charge the enemy. British Lieutenant-General Sir Giffard Martel (1889-1958) remarked, “Their bravery on the battlefield is beyond dispute, but the most outstanding feature is their astonishing strength and toughness.” Even Hitler’s generals considered Ivan to be special, especially when the Russian soldier “surpasses our adversary in the West in his contempt for death.”

One of the factors that influenced the Soviet soldiers’ life was Joseph Stalin’s “Great Purge” between 1936 and 1939. Stalin was paranoid about competition within the political and military ranks. So, he began to eliminate dissenting members of the Communist party including the political and military elite. The officer ranks in the Soviet army were decimated. More than 35,000 officers were removed from their ranks between 1937 and 1939. A year later, 48,773 were purged from the army and the naval fleet. On the eve of World War II, ninety percent of the military district commanders were gone. In other words, there wasn’t any experienced leadership for the ordinary soldier and skilled specialists were nowhere to be found. One of the effects was the soldiers’ attitude to the young and inexperienced officers. Rudeness and insubordination towards the new officers were commonplace and morale suffered. Desertion was a big problem, especially in the early years.

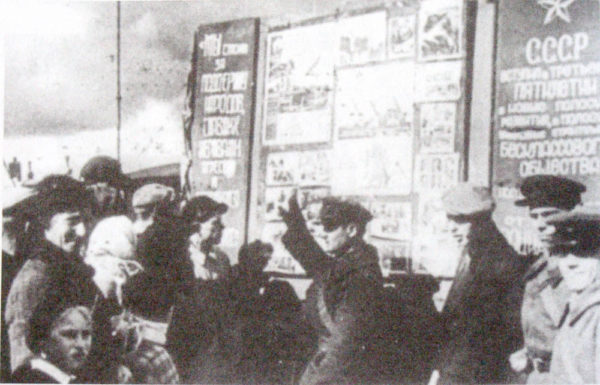

Politics took over for the lack of leadership. Every squad had a politruk, or political commissar. The politruk was a member of the Communist Party and the men were required to attend one session per day where it was pounded into their brains that class consciousness and Communist values were a higher priority than military issues. Many of the soldiers were illiterate and the job of dispensing the news fell to the politruk so, information could be manipulated (fake news?). The politruk was everywhere including target shooting, drill practices, and rifle handling. Their reports covered everything going on in the squad including discipline, record keeping, training exercises, and they were given ultimate authority to override commanders’ decisions if the politruk felt those decisions did not support the party’s principles.

Stalin began recruiting women during the summer of 1942. By the end of the war, 800,000 women served on the front lines alongside the men. The problems they faced included the mens’ attitudes toward them, uniforms were made for men and not did fit the women, latrine facilities were typically non-existent, and many of them had difficulty adapting to their new role. One skill the female soldier did possess was the ability to pick off the enemy with their rifle from a long distance ⏤ many of the female soldiers became snipers.

Daily Lives

The Soviet soldier could count on two things: hunger and exhaustion. Unlike the Americans and British, Stalin never gave his troops any time off. Simple pleasures like eating, basic hygiene (soap was scarce), shaving, repairing a uniform, or rest and recuperation had to be done in between their deployment duties. One thing all of them could count on was lice. It’s estimated that ninety-six percent of the men and women were victims of lice infestation. After getting under bandages and clothing, these tiny parasites ate the flesh and wounds. Disinfectant treatments were available but never eliminated the problem.

For troops in the rear, meals came twice a day: after sunrise and after sunset. For troops on the front lines, they could go hungry for days. Meat was often contaminated having been supplied by unsanitary slaughterhouses. A typical meal was some lumps of meat, black bread, and a “vile” cabbage soup. Soldiers were constantly suffering from diarrhea, food poisoning, stomach infections, or worse (e.g., tuberculosis).

Crime was a problem. One of the biggest issues was the selling of basic commodities from the warehouses and stores to local crooks. These were food items, footcloth material, coats, boots, and other rudimentary needs. Pilfering added to the downstream misery of the foot soldiers.

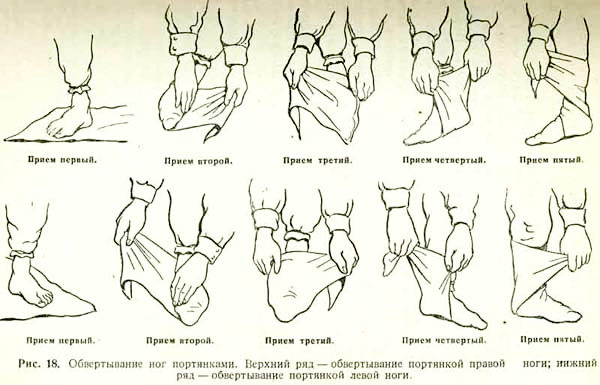

Soldiers wore heavy green uniforms with woolen trousers and a jacket. A belt, overcoat, and boots were issued to them. Linen undershirt and pants were turned in on an infrequent basis for laundering. A clean replacement set was handed out in exchange, but the items were previously worn by someone else including undergarments. Socks were not available unless the soldier could afford them, or someone knitted them a pair. They marched in footcloths, or portyanki ⏤ foot bindings were cheaper than socks. Strips of cloth were bound around the foot similar to wrapping an injured knee or ankle in an Ace bandage (socks were not routinely issued to Russian soldiers until 2013). Officers had privileges such as being given a handgun and a wristwatch. For the average soldier, getting a gun and ammunition was a luxury. Most of them slept on the ground and if one was lucky, they had straw beneath them at night.

The Soviet Myth

The Soviet Union myth presents the Russian hero as a simple, healthy, and strong person who is kind, selfless, and unafraid of death (this conveniently overlooks the thousands of deserters). He is looking towards the future ⏤ a bright vision of life. The Soviet Union’s hero myth has taken the shape of monuments, in patriotic songs, and poems.

Today, Russia stands behind two myths: the Soviet Union started the war on the right side, and autocracy was needed to win the war. Russian history books have been rewritten to exclude Stalin’s repression or the pact between Stalin and Hitler. A law was passed in 2014 criminalizing any criticisms of the Soviet Union and its efforts during World War II. President Vladimir Putin’s spin about the role of the Soviet Union was it “attempted to prevent the outbreak of World War II, but it practically remained alone and isolated.”

Historical facts prove this to be wrong. Re-writing history can be dangerous and morally repugnant.

Yes, I have purposely not addressed the atrocities committed by the Soviet army or soldiers. For a brief discussion on this subject, please visit the blog, After VE Day. Click here to read the blog.

This Yank will now sign off.

✭ ✭ ★ Learn More About Soviet Soldiers in World War II ✭ ★ ★

Betz, Dr. Astrid, Dr. Alexander Schmidt, Hans-Christian Täubrich. Translated by Ulrike Seeberger and Jane Britten. Memorium Nuremberg Trials: The Exhibition. Nürnberg: Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, 2012.

Merridale, Catherine. Ivan’s War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945. New York: Picador, 2006.

Click here to watch the video clip “What Did Soviet Soldiers Do Besides Fighting Germans During WWII?”

Ms. Merridale’s book is excellent. There are few accounts better than her descriptions of what the Soviet soldiers endured during the war. Thank you to Phil S. for turning me onto the book.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New with Sandy and Stew?

The manuscript of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (1940-1944) is now in the hands of my editor. Sandy and I are in the process of selecting images for the book. This is a lengthy and expensive process. One of the biggest challenges is finding images taken during the Occupation. The majority of available photos were taken by the Germans and most of them are archived in the Bundesarchiv. The problem is that if someone other than a German was caught taking photos, they were automatically classified as a spy and immediately shot (yes, it did happen).

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blogs.

Someone Is Commenting on Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Pat V., Glenys S., and David M. for their wonderful comments on our last blog, The Last Train Out of Paris. Click here to read the blog. Pat’s father, Stanley, was one of the 168 airmen on the train and Glenys, who is lives in New Zealand, was very good friends with Phil Lamason. He was the leader of the 168 men and responsible for saving the men’s lives. I enjoyed working with Pat and Stanley putting the updated blog together and I can’t wait for their book to come out sometime next year. I’m anxiously waiting for Amazon to deliver my copy of I Would Not Step Back … by Squadron Leader Phil Lamason RNZAF, DFC and Bar and assisted by Glenys.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2020 Stew Ross

Hi Stew,

I really enjoyed reading this week’s fascinating blog about the Soviet troops. My father recalls when they “liberated” luckenwalde Stalag luft 111A on 22nd April 1945 and immediately closed the Camp to keep the POWs as hostages until the end of May 1945 – it was a dangerous time because the Soviet troops were unpredictable; inebriated and trigger happy; they had been told to focus on reaching the English Channel and seemed indifferent to the wellbeing of the POWs and almost despised them for allowing themselves to be captured by the Germans.