Today is the 76th anniversary of Operation Neptune or D-Day as it’s commonly known. Neptune was the designated code name for the beach landings. The correct name for the overall invasion of Europe was Operation Overlord.

I’m sure the media and political focus on D-Day will be somewhat muted compared to last year’s anniversary. This year, the attention will be on the 75th anniversary of the end of the war (both VE and VJ days) and the liberations of the occupied countries and concentration camps. Much has been written about the hours leading up to launching the invasion, the experiences of the men during the early morning hours, the eventual success of driving the Germans back, and subsequent breakouts from the beaches. However, one aspect of the invasion seems to get scant, if any, attention.

What about the events during the thirty-six days prior to 6 June 1944? I’m specifically referring to the behind the scenes at General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF headquarters from 1 May 1944 up to the morning of the invasion. I’ll highlight some of the interesting events that took place on a day-by-day basis leading up to the men landing in Normandy.

Did You Know?

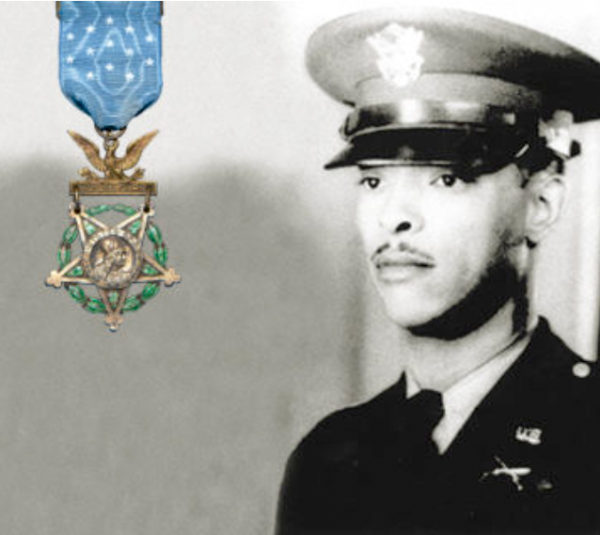

Did you know that it wasn’t until the 1990s that the United States Army determined that African American soldiers during World War II had been denied consideration for the Medal of Honor because of their race?

The day after Christmas 1944, First Lieutenant John R. Fox (1915-1944) of the 92nd Infantry Division – known as the Buffalo Soldiers – saw action in an Italian village. He was part of a small observation squad which volunteered to stay behind as the Germans began to overrun the village. From his position inside a stone tower, Lt. Fox directed the defensive artillery fire on the incoming Wehrmacht forces. At one point, he ordered the artillery to direct its fire on his position. Told by the artillery team the incoming onslaught would kill him, Lt. Fox’s last order was, “Fire it!” Lt. Fox’s sacrifice gave the American forces enough time to regroup, counterattack, and retake the village.

Lt. Fox and six other African Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor on 12 January 1997. Six of the medals were awarded posthumously with Lt. Fox’s widow accepting the honor on his behalf. The citizens of the village of Sommocolonia, Italy erected a monument after the war. It is dedicated to nine men killed during the battle: eight Italian soldiers and Lt. John R. Fox.

1 May 1944

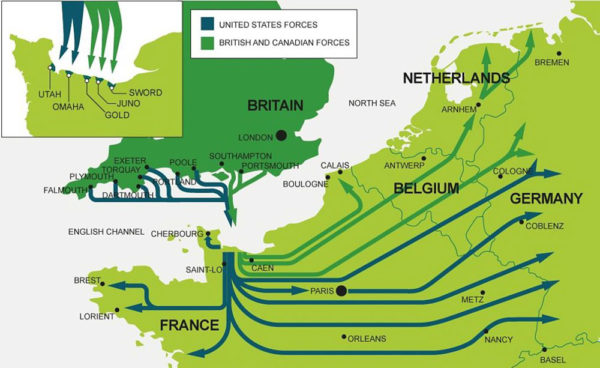

It was the first week in May when the final plan for Neptune was agreed upon. The initial date of the invasion, 1 May 1944, had earlier been postponed by General Eisenhower (1890-1969) and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976) after they decided to expand the original invasion plan drafted in August 1943 to include five rather than three divisions for the landings, an additional three airborne divisions, and extra landing craft. The revised plan also included specific goals for post-Neptune operations beginning with the break-out from the beaches.

In the months preceding the invasion, elaborate efforts were made to deceive the Germans about the actual landing location. This was called Operation Bodyguard and it was a complete success (Click here to read The Double Cross System). The final plans designated the lodgment or, landing area to be the beaches between the Seine and Loire rivers rather than Pas-de-Calais where Hitler and Rommel were convinced Allied troops would land.

2 May 1944

General George Patton (1885-1945) was ordered to report to Eisenhower. This came on the heels of Patton’s 26 April speech at a private gathering in England where he declared “… it seems to be the destiny of America, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union to rule the world, …” In the press releases, the Soviet Union was left out and there was a huge uproar. Marshall left it up to Ike to make the decision on what to do with Patton. Despite the popular option of firing Patton, Ike told him, “… (I will) use you to the fullest (extent) …” It seems Patton had more lives than a cat.

3 May 1944

Operation Fabius begins and will last until 9 May. Taking place along the southern coast of England, this would be the final dress rehearsal for the beach landings.

7 May 1944

Montgomery issued the plan for securing the lodgment area ninety-days after the landing (“D+90”). His assessment about increased mobility and tank warfare after clearing the bocage country and the hedgerows turned out to be correct.

8 May 1944

General Walter Bedell Smith (1895-1961), Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, requests permission to give General Pierre Koenig (1898-1970) some of the details of the invasion. Koenig is General Charles de Gaulle’s (1890-1970) chief delegate and representative to Eisenhower and the Allied High Command.

Smith knew the Allies needed to deal with the French for assistance in the invasion – much would be expected from the French Resistance and French military (i.e., air and navy) to ensure a successful operation.

Smith proposes two options: (1) inform a few French officers or allow de Gaulle to come to London or, (2) work through Koenig who would communicate with de Gaulle.

President Roosevelt says no. He doesn’t trust nor like Charles de Gaulle. Roosevelt considered de Gaulle to be too unpredictable and too independent to rely on. The president believed strongly that the Allies should not assume de Gaulle represents France. He cautions the Allied high command that Ike should be cautious when dealing with the French general. Roosevelt refused to recognize a French government before its people had the chance to decide for themselves. He prohibited Ike from discussing politics with de Gaulle as it might give the impression the Americans sanctioned the general as the head of state for France.

Eisenhower approves revised plans and timeline for the post-Neptune operation which included an advance on a broad front with the Ruhr as the main objective passing through the Ardennes. A secondary offensive to the south was agreed upon to create a diversionary deception. Despite the commonly held belief the war would be over in 1944, Ike informs the Joint Chiefs of Staff that it would take one year before the Germans would be defeated.

11 May 1944

Smith invites Captain Harry Butcher (1901-1985) to lunch. Butcher is the Naval Aide to Eisenhower and well respected by the high command. Smith divulged his concerns to Butcher about Operation Overlord. He estimated that once ashore, the troops would, at best, have a 50-50 chance of being able to secure the beaches. Smith was very worried about the underwater obstacles. Butcher’s diary indicated Smith was unsure the Americans were quite yet prepared for the invasion, matching British sentiments. One thing Smith divulged was that Ultra confirmed the Germans were still counting on the invasion to take place at Pas-de-Calais.

13 May 1944

Eisenhower informed Smith that he had decided to invite de Gaulle to London. Ike would require de Gaulle to stay in London until well after the landings. The French general would also be cut off from all communication with Algiers (Free French headquarters).

Smith thought this to be a bad idea as he felt de Gaulle would feel muzzled and it would be an affront to his honor (Churchill agreed). Unfortunately, Roosevelt had not given Ike or SHAEF (Supreme Allied Headquarters Expeditionary Force) an alternative French leader to de Gaulle. So, Ike and Smith were left communicating with General Koenig and the Comité français de liberation nationale or, French Committee of National Liberation (FCNL) ⏤ the defacto Free French government.

The FCNL was the resultant organization formed by the merger of the two respective political organizations of de Gaulle and General Henri Giraud (1879-1949), Roosevelt’s choice to lead France. Giraud was out maneuvered by de Gaulle and by mid-1944, General de Gaulle was the only option to lead the Free French. After the invasion, Roosevelt reluctantly supported de Gaulle as the leader of France.

15 May 1944

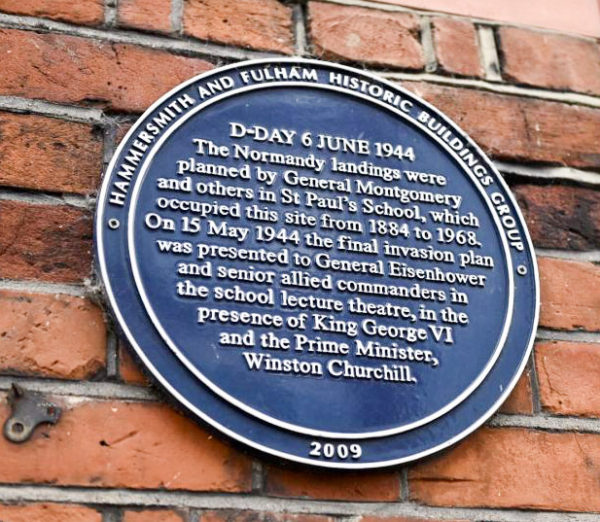

By now, the plan for Operation Neptune had been completed and the final briefing meeting was held in the auditorium of St. Paul’s School, Montgomery’s former school and now, his headquarters. King George VI and the prime minister, Winston Churchill, were in attendance as each of the Allied military leaders gave a choreographed briefing of the invasion and their individual responsibilities. As always, Churchill had the last word and indicated his support of an operation that up until that moment, he had serious misgivings (as did Montgomery). A large map was used for the briefing and was saved after the school was destroyed by a V1 rocket two months after the meeting. It can be seen today in the Montgomery Room at the rebuilt school.

At this point, the St. Paul’s presentations wrapped up the high-level planning for Neptune. All the commanders were in place and they each had their mission. Going forward, details would begin to fill in the outline of the plan. Clearly, invasion planning came right down to the wire with no room to spare.

By now, two large gaps in the planning process were obvious: American command and control of logistics once the invasion took hold and second, how to deal with de Gaulle and the French once on their soil. Click here to watch the video Allied Generals in Conference.

17 May 1944

Smith began to really tighten security. Forward areas were sealed off to all unauthorized persons and the press. The southern part of England was completely off limits to unauthorized people. Smith reversed himself and recommended discussions be held with the Soviets for the post-surrender period.

18 May 1944

Smith attends a meeting of the British Chiefs of Staff (BCOS) where he informed them of Ike’s decision regarding General de Gaulle. The BCOS vetoed the American decision regarding de Gaulle and the general refused to issue a D-Day statement to the French people. Ike gave Smith the responsibility for writing the statement. The statement was intended to reconcile the French civilians to the bombing campaign and the likelihood of civilian deaths during Operation Overlord (approximately 70,000 French civilians were killed by Allied bombs during the war).

During April, the bombing campaign caused friction between the British and Americans. Churchill did not want the railways bombed as it would likely cause French civilian deaths. However, Ike stood his ground and told the British, “…. the bombing of the railways was nothing to what was coming.” British Admiral Andrew Cunningham (1883-1963) correctly observed, “If we were not prepared to bomb France, we should never have entered on Overlord.”

Smith begins dealing with special operations in cooperation with the French Resistance. He authorizes Koenig to issue the D-Day warnings and action messages to the resistance groups.

19 May 1944

Smith issues a directive to Montgomery outlining the general principles and procedures regarding control of tactical air during Operation Neptune. The directive was really an attempt to reign in Air Chief Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory (1892-1944) who was in charge of all air operations for Neptune. Despite the backroom politics of British Air Marshals Arthur Tedder (1890-1967) and Arthur Coningham (1895-1948), Leigh-Mallory’s efforts proved invaluable for the invasion.

21 May 1944

Smith requests a statement from de Gaulle to be broadcast on D-Day.

26 May 1944

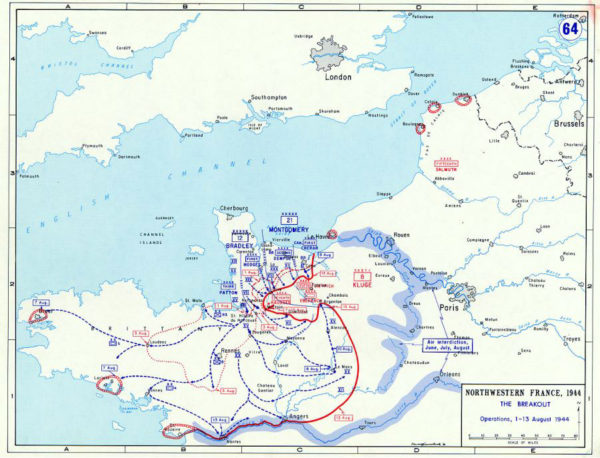

Eisenhower approves the final plan for Operation Neptune’s breakout. It was based on the assumption that the Germans, in retreat, would execute a scorched earth policy. The Allied route would take them through the Aachen Gap with a secondary movement through the Metz Gap.

The plan called for a five-phase operation in France. First, the landings and Brittany followed by an advance into an area between the Seine and the Somme. The fourth phase was liberating the ports of Le Havre and Rouen. Then, movements to Amiens-Reims, Arras-Mons-Maubeuge-Cambrai, and Antwerp-Aachen-Meuse-Siegfried Line.

Smith inaugurates the first daily meeting of the chiefs of staff. These were officers reporting to Smith with responsibilities including but not limited to security, planning, and liaison with the Allied governments as well as governments in exile.

28 May 1944

Smith orders all mail, incoming and outgoing, to be impounded. All private messages were forbidden.

30 May 1944

Churchill has lunch with the king who asks the PM where he would be located during the invasion. Churchill tells him he will witness the bombardment from a British cruiser. His Majesty immediately claims he will join Churchill off the shore of Normandy. This gets back to Eisenhower who refuses to take responsibility for what might happen to the British prime minister and the king. This matter was turned over to Admiral Ramsay who convinced the two that their rightful place was on land if serious decisions had to be made.

31 May 1944

While Eisenhower carefully avoided any personal contact with the Free French, Smith worked out a plan with Koenig to control the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). After the Allies secured the Normandy beaches, it was agreed that Koenig would take over command of the FFI. King George VI writes a letter to Churchill telling him that they would not personally witness the invasion and they were to remain in London. Churchill went into one of his “funks” with his full circle of ministers and advisors taking the brunt of his displeasure.

1 June 1944

The first weather reports came into Smith.

The forecasts were not good. The BBC broadcasts the first part of Paul Verlaine’s poem, Les sanglots longs/Des violons de l’automne … (The heavy sobs of autumn’s violins …). The coded message to the French Resistance told them to begin the sabotage of their assigned targets and that the invasion would take place within one month. Click here to read Dah-Dah-Dah-Duh.

2 June 1944

The issue of logistics finally came to a boil. Months had gone by with disagreements and politicking over how logistics were to be handled from an administrative and control standpoint as well as the team of officers responsible. Smith met with two of the principal logistic officers and it was determined the primary problem was how control was to be exercised by Ike: through SHAEF or through General Bradley’s headquarters (i.e., the “rear” vs the “front”). At this point in time, there was no appointed theater command for logistics and Ike was very disturbed. He threatened to put logistical control under SHAEF (an unpopular position with most, including General George Marshall) and ordered Smith to put all concerned in a room and don’t come out until a plan was agreed upon.

At 9:00 PM, Eisenhower held a meeting with Montgomery, Leigh-Mallory, British Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945), Tedder, and Smith. This meeting was to be repeated many times over the next few days. Thirty-minutes into the meeting, SHAEF meteorologist, Group Captain John Stagg, reported on the weather. The forecasted weather was “untrustworthy” but slightly “on the favorable side.” The invasion date of 5 June was now in jeopardy.

3 June 1944

Smith returned to London to deal with the logistics/supply command issue.

By mid-morning, Churchill arrived at Ike’s headquarters with a surprise guest: General de Gaulle. Smith’s deal with Koenig was now in jeopardy. De Gaulle would only cooperate if the Americans and British dealt with him exclusively on both military and political matters. He demanded political recognition as the rightful leader of the Free French.

All day, Ike and Smith tried to get de Gaulle to agree to deliver a statement to the French Resistance in order to unite their efforts on behalf of the invasion. Churchill gave Eisenhower permission to brief General de Gaulle on the invasion plans. Afterwards, the general agreed to make the statement as well as approving Smith and Koenig’s plan. Now the problem was that de Gaulle refused to deliver the statement written by the Allies. Over the next three days, de Gaulle vacillated between broadcasting and not broadcasting the statement.

That evening at the 9:00 PM meeting, it became apparent the invasion date would have to be postponed due to weather conditions (which was deteriorating as they met). Smith immediately left to issue the code word to all commanders.

4 June 1944

The weather that evening was windy and stormy with torrential rain. The nightly 9:00 PM meeting was held with the usual participants. Precisely at 9:30, Stagg reported that a thirty-six-hour break in the weather would occur the following day and continue into 6 June. A postponement would mean the earliest the invasion could take place would be 18 June (moon and tides).

Ike turned to Montgomery for his opinion. As ground commander, Montgomery owned the bulk of responsibility for the invasion. His answer was, “I would say go.” It was Smith’s turn and his response was, “It’s a helluva gamble, but it’s the best possible gamble.” Ike then said, “I’m quite positive that the order must be given.” The order is given for troops to begin the embarkation process.

General Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), the German commander for the defense of Normandy, returns to Germany for his wife’s birthday which is on 6 June. He believes the weather is too harsh for an invasion. Other high-ranking German officers assigned to Rommel’s command follow his example.

The Associated Press mistakenly reports the invasion has begun. The news is broadcast around the world. Five minutes later, the AP retracts the report and issues a correction.

5 June 1944

At 4:30 AM, the high command group convenes once more. More than 5,000 ships were converging on the assembly point but there was still time to call off the invasion. Stagg was invited in and reported that weather conditions were improving. A unanimous recommendation to launch the invasion was given to General Eisenhower. After a moment’s thought, Ike said, “Okay. Let’s go.” Click here to watch the video “The Decision That Changed The World”.

It only took thirty seconds for the room to empty. Smith immediately went to meet with Koenig to iron out a compromise regarding de Gaulle’s statement. It wouldn’t be until early the next morning when General de Gaulle would agree to address his fellow citizens of France.

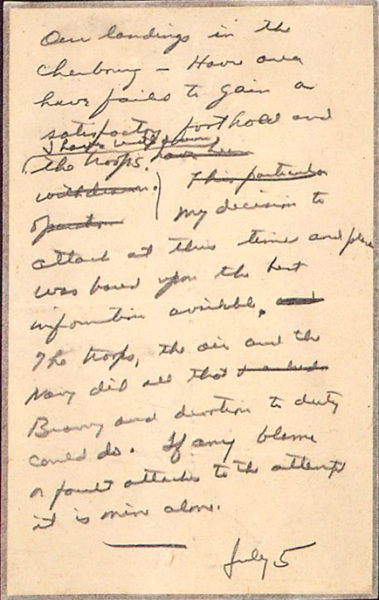

During the afternoon, General Eisenhower wrote out in longhand, a brief statement that he would deliver to the press in the event the landings failed. It read in part, “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.”

Around 8:30 PM, Smith accompanied his boss to Newbury where Ike addressed the 101st Airborne Division ⏤ the men who would parachute into Normandy ahead of the invasion. The two generals witnessed the men boarding the Douglas C-47 aircraft from which they would jump out of over Normandy several minutes after midnight. Click here to watch the video of Eisenhower and The 101st Airborne Division.

6 June 1944

After returning to SHAEF headquarters in the late evening of 5 June, Smith began an all-night negotiation session with the de Gaulle and the Free French delegation. Just before the sun came up, Washington finally agreed to de Gaulle’s demands and he decided to broadcast the statement into France. Moments after the sunrise, the first ships began firing on the German placements along the Normandy beaches.

The invasion had begun.

★ Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War: Closing the Ring, Volume 5. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1951.

Crosswell, D.K.R. Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

Mr. Crosswell’s book is long ⏤ more than one thousand pages. However, once you start it, you can’t put it down. It’s the story of how the war was managed by the Allies and specifically, General Eisenhower and his top aid, General Walter Bedell “Beetle” Smith. It is about Allied wartime strategies and tactics and the politics which decided many of the decisions. The military’s execution of these strategies is left to other authors and their books. Mr. Crosswell pulls the curtains open and the reader is able to see many wizards pulling the levers of World War II.

Mr. Crosswell wrote this book after he turned in his PhD thesis on the same subject. However, he later came to the conclusion that the thesis was inadequate in its breadth of coverage (spoiler alert: his thesis passed, and he was awarded his doctorate).

This is the book which provided the majority of material for today’s blog. It centers around Ike’s right hand man who was the “quarterback” and backbone for Allied High Command and in particular, SHAEF. After the war, Smith served as Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and Under Secretary of State.

The pressure on General Smith during the war years likely contributed to his various health ailments and an early death at sixty-five from a heart attack. He is buried near General George Marshall in Arlington National Cemetery.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Our little corner of the world came through the Coronavirus pandemic in relatively good shape. While we did, unfortunately, have deaths associated with the virus, it was certainly not the magnitude the experts had originally predicted (our area has a high percentage of senior citizens). The moment we got off the cruise ship on 7 March, Sandy and I went into “self-isolation” and never really had much contact with anyone from that time on.

Our friends in Paris, on the other hand, were strictly quarantined by their government. They had to remain in their apartments all day long with only a one-hour stretch allowed for exercise. It reminded me of prison schedules. If they had to go somewhere, official papers were required detailing why they were outside. The police would ask for and check their papers. This reminded me of the four years of German occupation. It seems the world is beginning to open up now (or at least today as I’m writing this blog). As with everything else, we will eventually return to normal. Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs.

It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Linda W. for her wonderful feedback concerning our blog, Something Must Be Done (click here to read). It’s the story of Suzanne Spaak who was responsible for saving the lives of hundreds of Jewish children. Suzanne had two children, Lucie (“Pilette”) and Paul-Louis (“Bazou”). Linda wrote to tell me how she met Pilette in 2013 and had the wonderful opportunity to visit her several years later.

Linda was flying over to Paris in 2013 when a woman sat down in the seat next to her. Pilette introduced herself to Linda and by the time they landed in Paris, Linda knew all about the amazing story of Pilette’s mother and their resistance activities. Afterward, Linda and Pilette stayed in touch via e-mail. In 2015, Pilette invited Linda to visit her at the apartment outside Paris. Linda ended up staying with Pilette for three weeks and they frequently took the train into the city where Pilette gave her the gold-plated tour.

During days when it rained, Linda stayed inside the apartment with Pilette. They would sit across from one another while Pilette knitted and Linda polished silverware. After Linda left, the two of them stayed in touch frequently until the summer of 2017. Pilette was having issues with her eyesight and had taken a bad fall which landed her in the hospital. Unfortunately, since then, there has not been any communication between them.

Linda’s visit with Pilette was right about the time Anne Nelson was researching material for her upcoming book, Suzanne’s Children. Ms. Nelson interviewed Pilette and you can read a more comprehensive account of Suzanne and her children in the book which was published by Simon & Schuster in 2017. It’s a very well written book and I think you would enjoy the story (except for one part). Click here for a link to the book.

Thanks again Linda for sharing this wonderful story with all of us. If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2020 Stew Ross

Good evening Stew,

I have just discovered your blog site and I am fascinated with the content. I am undertaking some detailed research on behalf of my Father Sqn.Ldr. Stanley Booker MBE who was shot down over France on 3rd June.

safa.org.uk/support-us/our-national-campaigns/ve-day-75/ve-day-stories/stanley-booker

My Father was betrayed to the Gestapo by Jean-Jaques Desoubrie and interrogated in Gestapo HQ in Paris and interned in Frenses before being transported by cattle truck to Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

I am looking for more detailed history about Desourbrie and who was his “puppet master”- ie who did Desoubrie report to. My Father is convinced there is a mystery about why some Resistance lines were left alone and no one arrested and other resisiders were arrested. Who was allowing Desoubrie to operate – have you any information. I am looking for Desoubrie’s Trail papers because it appears no allied airmen were invited to give evidence about his activities and betrayls.

I am compiling a list of the SS / Gestapo who were running operations in Paris. Cany you help please.

Thank you,

Pat