My aunt and three uncles served in World War II. Aunt Marge was a lieutenant and nurse who followed the 6 June 1944 invasion forces into Europe. Uncle Pete was an army sergeant serving in the Pacific Theater while Uncle Bill was the naval commander of a mine sweeping vessel in the Pacific. My mother’s only brother, Hal, enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force in 1942. He was a young P-47 Thunderbolt fighter pilot in Europe and completed 97 missions. Hal’s missions were primarily over Italy and then Germany. His primary responsibilities included destroying enemy assets such as rail lines, depots, manufacturing, or any target deemed necessary for destruction.

By August 1945, Germany and Japan had surrendered. More than 12.0 million American service men and women spread across 55 theaters of war needed to get home. One of the many vessels used to return them to the United States was the ocean liner, RMS Queen Mary. Stripped of its luxury furnishings and non-essential items, the ship was painted grey in 1939 and used as a transport ship.

Uncle Hal and 810,000 U.S. military personnel returned to America aboard the Queen Mary otherwise known as “The Grey Ghost.”

My aunt and uncles along with millions more like them came home and went on to become known as “The Greatest Generation.”

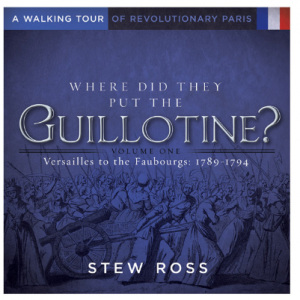

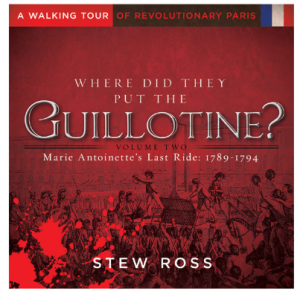

REVOLUTIONARY PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

These books are about Paris. They are about the places, buildings, sites, people, and streets that were important parts of the French Revolution. You are about to enter a journey into history beginning in 1789 at the village of Versailles with the procession of the Estates-General and ending on the Place de la Révolution with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794. This is your personal walking tour of the French Revolution as it occurred in Paris and Versailles.

Did You Know?

Did you know that an urban model for mixed-use residential, commercial, and parks is being developed? It is called the “15-minute city” and is based on one’s ability to get to the shops and parks within a 15-minute walk from your residence. Scholars at Massachusetts Institute of Technology are researching, quantifying, and measuring the “urban fabric” to see if this model can become a reality. As you may suspect, there are those who enthusiastically support an urban model like this while others bemoan the likely demise of the automobile.

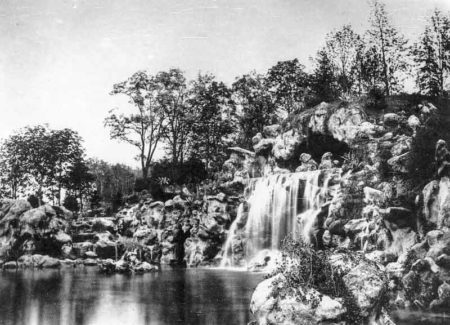

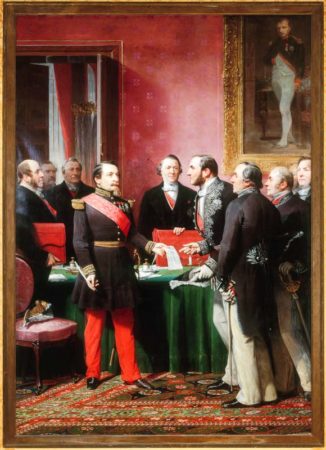

For those of you who have traveled in Europe, you are undoubtedly familiar with a city that was transformed in the mid-19th-century into a “15-minute walking city.” It is Paris. Napoléon III’s primary instruction to Baron Haussmann was to ensure every citizen could reach a park within a 15-minute walk. Prior to the seventeen-year “destruction and reconstruction” of the city, only forty-eight acres of parks existed. After 1870, more than 5,000 acres of new or expanded parks and twenty-four new squares were being enjoyed by the Parisians. Napoléon III’s goal of a “15-minute walkable city” had been achieved.

So, why spend millions and millions of dollars on studies when we can see and experience a contemporary example of the “15-minute city”? It does work.

Our next blog will be an expanded reprint of Charles Marville and le Vieux Paris.

(Click here to read The Missing Emperor and here to read Paris Digs.)

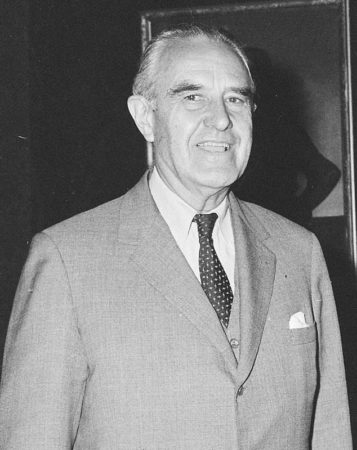

Operation Magic Carpet

By mid-1943, Gen. George C. Marshall (1880−1959), Army Chief of Staff, and others were sufficiently convinced Germany would ultimately be defeated. The general, a World War I veteran, was determined to avoid a similar demobilization debacle the army experienced in 1918-1919. However, twenty-five years later, he was faced with the same logistic issues but on a larger scale: how to get millions of service personnel back to the United States in a timely, orderly, and fair manner. He really couldn’t bring the men and women home until both Germany and Japan had surrendered. So, in July 1943, Gen. Marshall tasked the War Shipping Administration (WSA) to come up a plan for demobilization addressing which soldiers would remain in Germany, which soldiers would be sent to Japan to fight and finally, who would be the lucky ones to go home. The WSA was responsible for developing and coordinating the plan called “Operation Magic Carpet.” Read More The Grey Ghost