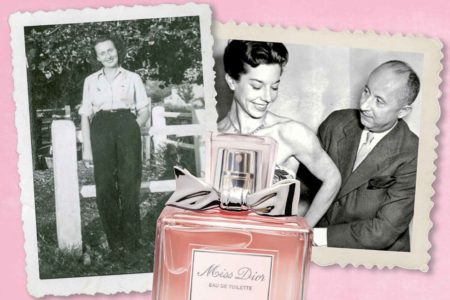

Several years ago, I wrote a blog about the famous fashion designer and perfume entrepreneur, Coco Chanel. (click here to read the blog Coco Chanel: Spy or Collaborator?) Today, we will focus on the sister of one of France’s post-war fashion trendsetters, Christian Dior (1905−1957). His famous perfume, Miss Dior, was named after his beloved younger sister, Catherine, who was a French resistance fighter during the German occupation.

Did You Know?

Did you know that shortly after Germany invaded and occupied neighboring European countries there was a widespread concern among the British that the Germans would soon invade England? In fact, Hitler had plans drawn up for the invasion (click here to read the blog OB West and here to read Professor Dr. Six) called “Operation Sea Lion.” The British developed a plan for the defense of their island with a contingency plan for the development of England’s last line of defense. Secret auxiliary units known as “scallywags” were formed by volunteers. These groups of elite fighters were scattered throughout England and Scotland and tasked with sabotaging the Germans as they advanced through the country. These men knew the countryside and were trained in guerilla tactics. One of the strategies was to build underground bunkers where they could lie in wait for the Germans to pass by before emerging to attack. About five hundred bunkers were constructed around England. However, very few have ever been found and when one is found, it is purely by accident. The “scallywag” units were one of the most secretive British operations and the men who signed the Official Secrets Act never divulged their mission, often taking the story to their graves.

The bunkers measured about twenty-three feet long and ten feet wide. You entered through a hatch and exited from a rear hatch. These bunkers were stocked with enough food, weapons, and supplies to last five weeks for the seven soldiers who would occupy the bunker. The men knew that in case of an invasion, their life expectancy would likely be a maximum of two weeks. They recognized they had signed up for a suicide mission.

The few bunkers that have been found remain classified with respect to their locations. The government has converted the bunkers to artificial caves for bats to roost in.

Catherine Dior

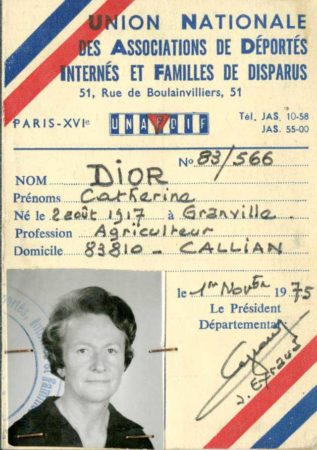

Ginette Dior, or better known as Catherine Dior (1917−2008), was born in the coastal town of Granville on the western side of Normandy, south of Cherbourg-en-Contentin, near where the English Channel meets the Atlantic Ocean. Her family was financially well-off and lived in a large home known as Villa Les Rhumbs. She was the youngest child of Maurice and Madelaine’s five children: three brothers (Raymond, Christian, and Bernard) and a sister, (Jacqueline). The two closest siblings (albeit separated by twelve years) were Catherine and Christian. They shared a passion for gardening, art, and music. By the time Catherine was born, the family had moved to Paris, but they kept Les Rhumbs. The economic disaster of the early 1930s destroyed her father’s fertilizer company and after the death of her mother in 1931, Catherine and the rest of her family moved to Provence where her father purchased farm property known as Les Naÿsses near Callian, France.

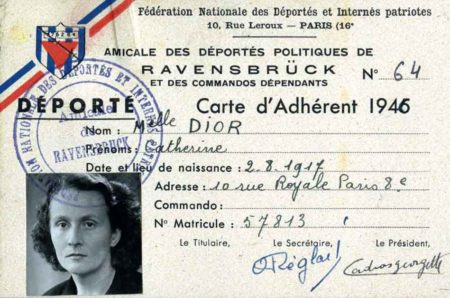

Christian took his younger sister under his wing and by 1936, Catherine had moved into her brother’s Paris apartment at 10, rue Royale (steps from the famous Maxim’s de Paris restaurant). Christian was an up-and-coming freelance fashion illustrator and Catherine likely modeled for her brother’s early designs. The late 1930s was a spectacular time for brother and sister. They lived a bohemian life with many friends and many parties.

However, when the Germans marched into Paris on 14 June 1940, everything changed. Christian and Catherine left Paris and moved to their father’s small farm in Provence where they raised vegetables and roses. By the end of 1941, Christian returned to Paris to design fashions for the renown couturier, Lucien Lelong (1889−1958). Catherine remained at the farm in Provence which was part of the unoccupied zone controlled by the Vichy collaborationist government.

Christian Dior and the “New Look”

Christian Dior (1905−1957) was devoted to his younger sister and Catherine was equally devoted to Christian besides being fiercely proud and defensive of her brother to the day she died. Selling fashion sketches, Dior was hired in 1937 to work for the fashion designer, Robert Piguet, who taught Dior many of the techniques he would use during his career. Dior was called up for military duty but when his army unit was demobilized in 1942, Dior returned to Paris where he resumed his fashion career under Lucien Lelong. Dior and Lelong’s other primary designer, Pierre Balmain, stayed with the couturier throughout the occupation. Along with other Paris fashion houses, they designed dresses for the wives of Nazi officers, French collaborationists’ spouses, and female collabos. During the first show of 1943, Balmain and Dior stood next to one another while viewing the audience of collaborationists and Dior said, “Just think. All those women going to be shot in Lelong dresses.”

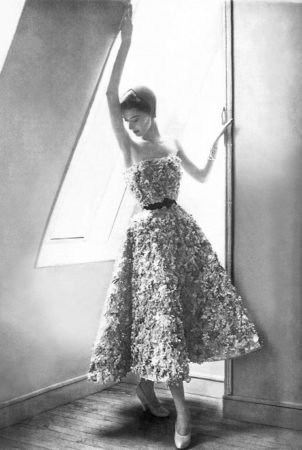

After the war ended, Dior opened his own couture, Christian Dior SE. (Now owned by LVMH.) His breakout show in February 1947 at 30, avenue Montaigne (8e) introduced his first designs based on flowers (“I have designed flower women”). The show and the clothes were a hit, and the editor of Harper’s Bazaar coined the term “New Look” to describe Christian’s designs. Dior believed postwar fashions up to that point were too reminiscent of ugly Vichy fashion. He used quite a bit of fabric in his designs and that didn’t go over too well in France considering everyone was still under rationing. Women complained his dresses covered up their legs. Coco Chanel said of Dior’s new look, “Look how ridiculous these women are, wearing clothes by a man who doesn’t know women, never had one, and dreams of being one.” (Chanel was still in self-imposed exile in Switzerland due to her wartime collaborationist activities.) Once rationing was a thing of the past, everyone got over their austerity issues. Paris was once again the epicenter of world-wide fashion and Christian Dior was proclaimed a genius.

Resistance Activities

In November 1941, Catherine met Hervé des Charbonneries. He was married with three children, but Catherine didn’t care. She fell deeply in love with him. Hervé was in an “open” marriage and his wife, Lucie, did not mind his blossoming relationship with Catherine. (Hervé and Lucie would eventually divorce.) Hervé was a resistance fighter (résistant) with the British-sponsored Franco-Polish resistance group known as Famille, later named, “F2.” He recruited Catherine and Lucie to join him in his resistance activities in the unoccupied zone. F2’s primary mission was espionage with the intent to gather intelligence on the Germans. After the German army invaded the unoccupied zone in November 1942, it became increasingly dangerous for résistants and foreign agents (e.g., British-led Special Operations Executive). The Nazi party intelligence agency, Sicherheitsdienst (SD), along with Vichy agents (e.g., the Vichy paramilitary Milice) and collabos (e.g., Bonny Lafont Gang) increased their efforts to hunt down and infiltrate resistance networks.

By the summer of 1944, the SD and the Milice were having great success in breaking the networks, arresting resistance fighters, and either executing them or deporting them to the concentration camps. Catherine left southern France after F2 had been infiltrated. She returned to Paris in June and stayed in Christian’s apartment on rue Royale where she promptly resumed her resistance work with F2. Unbeknownst to Catherine, a female collabo of Friedrich Berger’s group, nicknamed “The Gestapo of Rue de la Pompe,” (click here to read the blog Captain Jack) had infiltrated the F2 network in Paris. Catherine arrived at the place du Trocadéro on 6 July to meet with Madeleine Marchand, the female double-agent infiltrator. Berger’s men were there to arrest Catherine and she was taken to their headquarters at 180, rue de la Pompe. As a result of Marchand’s infiltration, twenty-six other F2 résistants were arrested. Berger’s headquarters was used as a place where the victims could be tortured until they gave up valuable information.

French collabo units such as Berger’s group and the Bonny Lafont Gang were known to be more vicious and crueler than the Germans in dealing with their prisoners. According to Catherine’s account given at the trial of Berger and his fellow collabos, she was immediately subjected to interrogation. This was accompanied by brutalities such as kicking, slapping, etc. When that didn’t work, Catherine was taken to the bathroom where they gave her the “bathtub” treatment. In other words, they held her under water until she almost drowned and then yanked her head up at the last minute to breath. This was repeated for forty-five minutes but Catherine never broke. After this, she was taken to Fresnes prison and two days later, brought back to rue de la Pompe. This time, the torture included being submerged in icy water for hours. By not talking, Catherine saved her brother and other F2 colleagues including Hervé from arrest. Resistance archives have recorded her bravery as “exemplary courage” when subjected to “particularly odious” forms of torture.

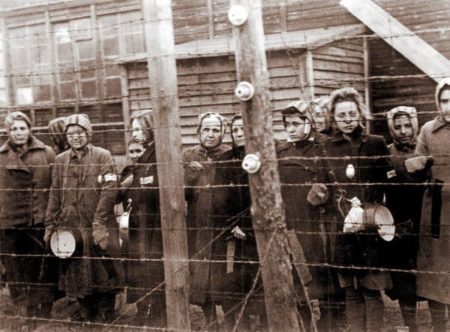

On 15 August 1944, Catherine was put on the last train convoy to leave Paris. (Click here to read the blog The Last Train Out of Paris). There were 2,200 people stuffed inside the cattle cars at the Pantin rail station. These men and women were political prisoners, résistants, and captured downed Allied airmen who the Nazis considered to be “terrorists.” The men were bound for KZ Buchenwald (where the airmen were scheduled to be executed) while the train would stop first at KZ Ravensbrück where the 550 women would be delivered first (click here to read the blog The Rabbits of KZ Ravensbrück). Catherine was subsequently transferred to several Buchenwald sub-camps where she worked on German munitions and armaments. One of the sub-camps, KZ Abteroda, exploited its women prisoners by “renting” them out to BMW to manufacture chemicals to be used as blasting agents. Catherine’s lungs were permanently damaged as a result of working closely with toxic chemicals. One of the prisoners’ priorities (besides staying alive) was to sabotage the machinery they were working with. The women slept on concrete floors, consumed watery soup and dry bread, and suffered brutal beatings by the guards.

As the Soviet army made its way across eastern Germany in 1945, the concentration camps were emptied with prisoners forcibly marched to the west. Outside Dresden, Catherine was able to escape from the “Death March.” She was picked up by Allied troops and in May, made it back to Paris.

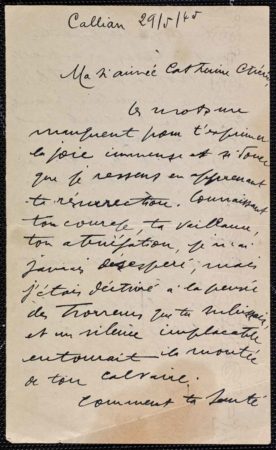

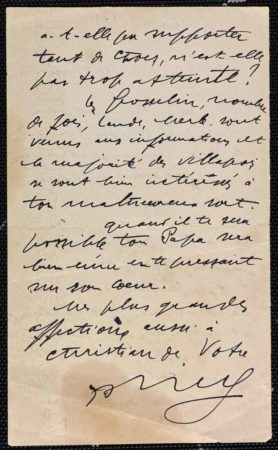

Christian Dior found out about his sister’s arrest and deportation and made numerous attempts to get her freed. Despite his connections with well-placed people, including his clients, he was unsuccessful. It wouldn’t be for another nine months before he learned she was still alive. Finally in May 1945, Christian was informed his sister was returning to Paris and he met her at the rail station. Due to her emaciated state, Christian did not immediately recognize her. Catherine was so ill that she couldn’t eat the special dinner her brother prepared for the occasion. Catherine needed many months to recuperate but she would suffer the rest of her life from insomnia, nightmares, memory loss, anxiety, depression, and what we know today as PTSD. Catherine developed a hatred for Germans and could not bear to hear Germans talking nor seeing cars in France with German license plates.

“Gestapo of rue de la Pompe” Trial

Fourteen former members of the “Gestapo of 180 rue de la Pompe” (click here to read the blog Captain Jack) were arrested and put on trial in November 1952. Catherine was called to testify against the defendants. Unfortunately, Friedrich Berger was not present in the dock. He was tried in absentia, convicted, and sentenced to death. Berger cheated the firing squad and died of a sudden illness in Munich in 1960.

Les Halles and the Flower Market

Catherine inherited her love of flowers from her mother. She and Hervé began a flower brokerage business after the war. From the late 1940s through the 1950s, they would arrive at Les Halles (Paris’s giant market) every morning at 4:00. There they would begin brokering deals with florists around the world. Catherine was granted a government license to act as a Mandataire en fleurs coupées, or “Agent in cut flowers.” She was only one of several women awarded the license to broker and sell flowers internationally. The couple (Catherine and Hervé never married) also grew and sold flowers from Les Naÿsses.

Post-War

Catherine and Hervé took over Les Naÿsses after the death of her father in 1946 and continued to grow the flowers coveted by perfume manufacturers. Christian Dior purchased the Château de la Colle Noire in 1951, three miles from his sister’s property. Christian died of a heart attack after choking on a fishbone at dinner. After Christian’s death in 1957, Catherine sold his estate. However, in 1993, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) purchased and renovated the property and Catherine, who kept her brother’s art and furniture, returned them to the château. Les Rhumbs had been sold to the town of Granville in the 1930s and converted to a public park. By the 1990s, Les Rhumbs was turned into a museum dedicated exclusively to Christian Dior and his couturier career. His faithful sister served as the museum’s honorary president preserving Christian’s legacy until her death in 2008.

Catherine Dior is buried in Callian near her brother’s grave.

★ Learn More About Miss Dior ★

Buckmaster, Maurice. They Fought Alone. London: Biteback Publishing Ltd., 2014. Page 248. (Original edition published by Odhams Ltd. In 1958).

Chaney, Lisa. Coco Chanel: An Intimate Life. New York: Penguin Books, 2011.

Picardie, Justine. Miss Dior: A Story of Courage and Couture. London: Faber & Faber, 2021.

Sebba, Anne. Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved, and Died in the 1940s. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017.

Veillon, Dominique. Translated by Miriam Kochan. Fashion Under the Occupation. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2002.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Well, we might be making some progress with respect to finding a solution to our binding issues for the new book. (The book is printed and waiting to be bound.) Pollock Printing found a third-party who has the machine that uses the heavy-duty glue necessary to bind a book of this thickness using 80-pound paper. I’ve asked Alex Pollock to send the book proof to Roy (our book designer) for his review. Roy is on the same page as we are with respect to demanding high quality. On Monday, Sandy, myself, and Roy have a conference call with Alex Pollock to discuss the situation. We’re looking forward to having the book available for you.

The good news is that the electronic version of the new book will be out on Amazon within a week. Doris and her crew at AuthorLink always do a great job for us converting the file into e-publications (both Kindle and iBooks). The e-pub version is not meant to be viewed on anything smaller than a tablet. (Sandy proof-reads the electronic files on a Kindle Fire 7 which is the smallest size tablet we would recommend. We would definitely recommend against an Amazon Paper White, it needs color display to read well).

I’ve asked Sandy to put together a link so you can view parts of the book. If all goes well on Monday, shortly after we will send out a special blog with the link so you can preview the book.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Dominic L. from Dublin, Ireland for contacting us regarding the blog, Racer, Spy and the Erotic Model (click here to read). Dominic is very familiar with the Irish painter, William Orpen and the relationship between Orpen, William Grover Williams, and Yvonne. One of the interesting tidbits Dominic shared with me concerned Orpen’s painting of Yvonne that was brought onto BBC Roadshow. It was later determined that the painting was a copy (i.e., a fake and not painted by Orpen). Thanks Dominic for sharing this information.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Another remarkable story about truly amazing people and a World War that is either completely unknown, or largely forgotten today. Many thanks for keeping this important history alive.

Hi Greg; Always good to hear from you. Glad you enjoyed today’s blog. I appreciate your kind comments, as always! STEW

Hello, I’m confused about your reporting that Friedrich Berger died in 1960. I have read several other resources that state he moved to America in 1959, and in 2021 at the age of 95 he was found and deported to Germany to face his crimes, but died soon after. Can you clarify for me? Thank you!

Hi Rachel; Thanks for reaching out to us. I think you are referring to Friedrich Karl Berger who was accused and put on trial as a former guard at KZ Neuengamme. Your facts regarding Berger appear to be correct. However, the Friedrich Berger I refer to in the blog is a different person. Our blog, Captain Jack, also addresses Berger’s activities in Paris during the occupation. I hope that clears up any confusion. STEW